And we’re bound for the border

We’re soldiers of fortune

And we’ll fight for no country, but we’ll die for good pay

Under the flag of the greenback dollar

Or the peso down Mexico waySteve Earle, “Mercenary Song,” Train a Comin’, 1995.

Whenever a “filibuster” is brought up in common parlance today, it is normally in reference to a legislative tactic whereby someone delivers a speech for an excessively long time in order to stall a vote. That is not the type of filibuster discussed in today’s article. The tale of the term filibuster is soaked in the blood, sweat, and gore of thousands of English, French, and American pirates and patriots who died to satiate the expansionist thirst for land and profit. The American Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas was not peacefully purchased; it was conquered.

In the early to mid-19th century, American adventurers had a get-rich-quick scheme for land piracy that could be distilled into a general formula:

Acquire political backing from politicians who see the addition of new land as a geopolitical boon.

Sell bonds and promise land to wealthy patrons in exchange for funding to acquire guns, ships, and mercenaries. Bonus points if American business interests have a foothold in the targeted territory before the invasion.

Invade a lightly defended Spanish colony with an irregular paramilitary force and topple the tin-pot colonial administration.

Declare independence.

Apply to America for annexation.

Get annexed by the United States before the Spanish can mount a decisive counteroffensive. If the U.S. refuses to annex the territory, politely ask to be made into a protectorate territory of the “informal empire” or “economic sphere of influence.”

Sell off the newly acquired territory for profit.

This strategy was the result of two centuries of almost continuous Anglo-American raiding and conquests of the Spanish Empire. This formula was then adopted as official U.S. foreign policy and formally implemented by the State Department against the Spanish during the Spanish-American War; and then again, against all of Latin American and Hawaii, in the twentieth century.

Elizabethan Origins of Anglo-American Piracy

The term filibuster is Dutch in origin, coming from the 16th century word vrijbuiter, or “freebooter,” describing pirates and privateers. This term was adopted by the French, whose term flibustier described French-aligned 17th century West Indian sea rovers, pirates, and privateers. These same flibustiers were referred to as buccaneers by the English.

From October 12, 1492, until the early 1600s, the Kingdom of Spain retained a near monopoly on the exploitation of the New World. Following the discovery of the Americas by Christopher Columbus, the Spanish embarked on a ravenous bid to topple the old native empires of the Americas, divvy up the newly conquered land into viceroyalties with colonial administrations, convert the natives to Roman Catholicism, and use the labor of the natives to extract as much silver and gold from the land as possible. From 1494 onward, under the Treaty of Tordesillas, the King and Queen of Castile, Leon, Aragon, Sicily, and Granada were granted lordship over the entirety of the New World, aside from the eastern tip of Brazil, which was delegated to the Kingdom of Portugal.

From 1560 to 1685, between 25,000 and 30,000 tons of silver were produced in Spanish American mines, predominantly in modern-day Mexico and Peru. Most of these precious metals were shipped in treasure galleons like the famous Manila Galleons, which traveled from Manila, Phillipines, through trading hub ports Veracruz and Acapulco, and then on to Cádiz, Spain.

A substantial portion of this newfound wealth funded Continental European mercenaries and large armies who fought in the Wars of the Reformation on behalf of the Habsburg Dynasty’s Empire. Starting in 1517, the Protestant Reformation kicked off a century and a half of bloody, unremitting sectarian conflicts. The Habsburg Dynasty of Spain spent their vast coffers of colonial treasure on fighting continental European wars: in Italy against the French Valois Dynasty; against England and the Dutch Republic in the Eighty Years’ War; and, finally, ending with the Thirty Years’ War from 1618 to 1648.

While Spain was establishing its overseas empire and fighting both their France neighbors and their continental Protestant adversaries, the Kingdom of England was undergoing the English Reformation. In the early 16th century, Henry VIII formed the Church of England, breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church. Although Henry VIII rebuked Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses in a letter and Henry himself had very few qualms with Catholic theology beyond Papal control, his break from Papal authority allowed for Calvinists and other Protestant Dissenters to infiltrate and steer the Church of England. Over the next century, Protestantism would grow in England from a small elite cadre of Reformers to the accepted orthodoxy for the majority of the English people.

Following the death of Henry VIII, Mary I married Prince Philip of Spain and attempted to reestablish the Catholic Church as the state church of England. Over Mary I’s brief five-year reign, she executed approximately 287 Protestant Dissenters and drove over 500 Protestants into exile. These high-profile pyre burnings were aimed at the upper echelons of English society. Many lords, canon professors, and well-to-do Protestants who had been loyal to Henry VIII were imprisoned, tortured, and burned, including, notably, the former Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer and three Protestant women (one of whom was pregnant and allegedly in labor during the public execution) in 1556. Two tomes detailing Catholic atrocities against Protestants in England in particular and in Europe in general were compiled by John Foxe in what would later be colloquially known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

The Protestant Reaction against Bloody Mary I came in the form of Queen Elizabeth I’s reign. Between 1558 and 1603, Elizabeth I engaged in a campaign of nation-building and military expansion. Elizabeth I rebuked her half-sister’s pro-Spanish foreign policy by sponsoring piracy and raiding against her Catholic rivals as well as encouraging the first English settlements in the Americas. The three great privateers of the Elizabethan Age were Sir John Hawkins, Sir Francis Drake, and Sir Walter Raleigh, all impassioned Protestants hailing from Devonshire, England.

The reign of Elizabeth I oversaw the transformation of the English navy from a loose feudal patchwork of nobles fielding medieval cogs to the construction of the first Royal man-o’-wars. The liminal space between private lords fielding their own ships and the royal authorities manning royal vessels was the advent of the English privateer. English lords would invest in pirate ships that were chartered and partially funded by Elizabeth I herself. The purpose of these privateers was to engage in clandestine raiding against enemies of the state. Even though these privateers might have been captained by English lords and partially funded by the English monarch, they still permitted Elizabeth herself some diplomatic plausible deniability. When questioned by Habsburg diplomats about the damage caused by English privateers, Elizabeth could feign ignorance and respond with the simple response: “It wasn’t me.”

Sir John Hawkins was the first English merchantmen to conduct the Triangle Trade. In the 1560s, Hawkins would capture African slaves on the Ivory Coast, sail to the Spanish Americas, force the Spanish to buy his slaves under the threat of being attacked by Hawkins’s fleet, and then bring Spanish wares to England. Hawkins took his family friend Francis Drake on his first voyage. On Hawkins’s second voyage, he attempted to resupply a French Huguenot colony at Fort Caroline in modern-day Florida, although the Spanish would massacre the entire colony only a few months later.

England’s flagrant disregard for Spanish law and France’s brutal extermination of its Protestants continued to drive a wedge between Protestant England and its Catholic rivals. Meanwhile, news trickled to England about the Spanish Inquisition torturing and burning to death 46 Protestants in Lima, Peru, 59 Protestants in Mexico City, and around 100 Lutherans in mainland Spain between 1558 and 1562. Tales of Spanish cruelty to the natives in the Americas and sadistic religious repression against their own people culminated in what has been dubbed the Black Legend. This perception of the Spanish Empire drove a tremendous amount of English Protestant diplomatic animosity against the Spanish colonies. At the same time, English raiding and subterfuge would cause Spanish merchants to be wary of English ships on the high seas, whether the two nations were presently at war or not.

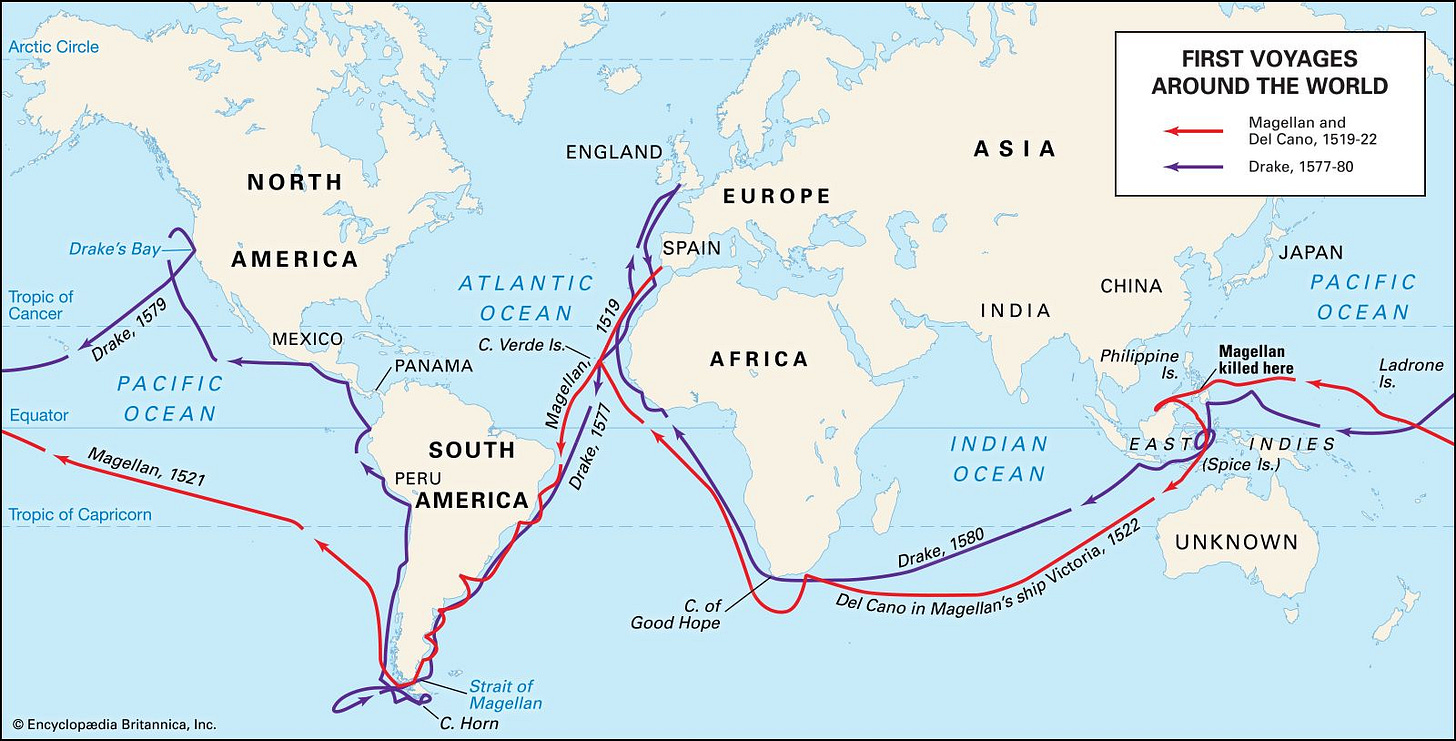

After learning the intricacies of Elizabethan trade, seamanship, and diplomacy, Francis Drake embarked on his privateering mission against the Spanish. Even though England and Spain were formally at peace, Drake sacked several Spanish towns, raided Spanish treasure galleons, and looted Spanish mule trains in Panama that were transporting gold. The profits of Drake’s first expedition were then invested into Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe. Drake and his five ships set off from England, plundered Portuguese and Spanish ships along Cape Verde and along the South American coast, and then arduously sailed through the Strait of Magellan. By the time Drake sailed around the treacherous tip of Cape Horn, he only had one ship left in his fleet, the Golden Hind. Drake then raided the undefended coasts of Spanish Chile and Panama before capturing one of the greatest prizes in the history of piracy, the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, a 120-ton treasure gallon laden with 26 tons of silver and 13 chests of golden valuables. Drake then continued to raid Central America and sailed as far north as modern-day Oregon. Every Sunday, Drake would read passages from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer and occasionally read chapters from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs to instill in his crew the moral weight attached to England’s crusade against Catholic tyranny. Throughout the Spanish Main, fearsome tales of Francis “El Draque/The Dragon” Drake would spread like wildfire.

When Drake arrived back in England, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth, who received a 4,700% return on investment for outfitting Drake’s voyage. Sir Francis Drake was the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe, and he also invented what would be called the Pirate Round, a sailing route used by pirates to circle the globe while optimizing weak targets in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

While Francis Drake navigated the globe, Walter Raleigh made a name for himself as a pro-Huguenot mercenary in the French Wars of Religion and as an officer in the English army to suppress the Irish Desmond Rebellions. Raleigh quickly earned himself a knighthood and a vast Irish plantation as he gained the good graces of Elizabeth I.

The first English royal charter to settle the Americas was originally given to Walter Raleigh’s explorer and privateer half-brother Humphrey Gilbert. Gilbert died in 1583, leaving the charter to Raleigh. In 1585, after sending several exploratory expeditions to the American East Coast and naming the region “Virginia,” Raleigh sent Richard Grenville, 600 men, and seven ships to settle Roanoke Island in modern-day North Carolina. This “Lane Colony” only lasted for several months before all of the settlers returned to England due to the hostility of the natives and threat of Spanish invasion. On the trip back to England, Grenville went out of his way to attack stray Spanish treasure galleons. A year later, Sir Francis Drake transported 108 settlers to settle Roanoke again. That same year, Drake invaded the Spanish island of Hispaniola with 1,500 men and ransomed the city of Santo Domingo. Unfortunately for the colonists, Drake was unable to return with supplemental supplies and more colonists due to the ongoing war with Spain. When Drake returned in 1590, the Roanoke colonists had disappeared without a trace.

The entire span of Elizabeth I’s reign saw England engage in proxy wars and tit-for-tat commerce raiding with Spain. Since 1566, Habsburg Spain waged a war of religion against Calvinist Protestant rebels in Holland. These rebels were supported with arms and financing by Protestant England. Meanwhile, Spain and Portugal supported Irish revolts against English authorities in the Second Desmond Rebellion. These conflicts escalated into the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604).

The Roanoke Colony might have survived, but Francis Drake and John Hawkins were prevented from resupplying the colony as they were conscripted into the English effort to fend off the Spanish Armada in 1588. In 1589, the English would launch a failed English Armada to liberate Portugal from the yoke of Spanish rule, and the Spanish would send a second and third armada against England in 1596 and 1597. The Anglo-Spanish War concluded in 1604 with the Treaty of London. The treaty stipulated that the English put an end to their state-sponsored piracy against Spain, their attempts to establish colonies in the New World, and their subsidies for Dutch rebels; and that the Spanish stop sponsoring Catholic uprisings in England and Ireland.

Buccaneers and Bounties

Following the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, her cousin James Charles Stuart of Scotland, son of Mary, Queen of Scots, ascended to the English throne, becoming the King of England and Ireland but also of Scotland. From the reign of the James I to the beheading of Charles I in 1649, the Stuart Dynasty would pepper the Caribbean and North America with colonial pioneers and pirates.

The Stuart Dynasty would charter fledgling colonies in Virginia (1607), Bermuda (1609), Massachusetts (1620), Newfoundland (1620), St. Kitts (1623), and Barbados (1625). These colonies were initially founded under the presumption that gold and silver could be extracted from the natives and land; however, the English colonial economies quickly pivoted to growing cash crops, most notably tobacco.

Similar to the English, the French had no luck in seeding the Americas with their own colonies in the 16th century, with half a dozen aborted attempts to establish settlements in modern-day Quebec, Maine, and Florida. However, the French were able to begin their oversees empire in earnest with colonies in Port-Royal in modern-day Nova Scotia (1605); Quebec (1608); and Montreal (1642).

For much of the 16th and early 17th centuries, the French were the geopolitical rivals of the Spanish Habsburgs. France may have been a staunchly Catholic monarchy, but its borders were encroached on by Spain in the south, Spanish Netherlands in the northeast, Habsburg Naples to the southeast, and the Habsburg Holy Roman Empire to the east. In response to Habsburg territorial encouragement, France turned to piracy.

While England sponsored privateers Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh, and John Hawkins to attack the Spanish Empire, France conducted their own sponsored privateer raids featuring Jean Fleury, François Le Clerc, and Jacques de Sores: Fleury captured two out of the three treasure galleons belonging to the conquistador Hernán Cortés in 1552; Le Clerc pillaged Santiago de Cuba and attacked San Germán, Puerto Rico, in 1554; and de Sores sacked and burned Havana, Cuba, to the ground in 1555.

The Dutch established the Dutch West India Company (WIC) in 1621. In 1624, WIC settled 30 families on modern-day Governors Island, New York City. WIC then attempted to invade Portuguese Bahia, Brazil, in 1625 as part of the ongoing Dutch-Portuguese War, but they were rebuffed. WIC continued to send ships of settlers to northern Brazil to set up sugar plantation colonies in 1630, but these were eventually ousted by 1654.

The colony of New Amsterdam would come into conflict with New Sweden, a colony of roughly 200 Swedes, established in 1637 in modern-day Delaware. The official Dutch colonial chapter claimed ownership of the entire Delaware Valley, so in 1655, after the start of the Second Northern War, the WIC took the opportunity to claim the territory. In August 1655, several hundred Dutchmen and seven ships seized New Sweden in a bloodless invasion. The colony of New Netherlands was, in turn, conquered by England in 1664 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

The English and French were able to establish small settlements in the sparsely populated wilderness of North America, but they could not seem to gain a foothold in the heavily defended Spanish Caribbean. The foot soldiers of the Anglo-French invasion of the Caribbean would become known in English as buccaneers and in French as filibusters.

In the early 16th century, Spanish colonists released domesticated horses, pigs, and cattle on Caribbean islands as a source of hunting meat to feed future generations of settlers. In the 1620s, French Huguenots began to hunt these wild pigs and cattle on the Spanish island of Hispaniola and smuggle the meat and provisions they could gather to the locals.

In 1629, the Spanish general Don Fadrique de Toledo tried to evict 3,000 English and French colonists from the island of St. Kitts. Many of the French hunters on Hispaniola and English-French colonists fled into the woods, regrouped, and migrated to Tortuga — a small, rocky, mountainous island off the coast of Hispaniola settled by a few Spanish tobacco planters. From 1630 until 1688, French and English buccaneers would hunt wild pigs and cattle on Hispaniola, sell their goods on Tortuga, and then use Tortuga as a recruiting ground and launching pad for English, French, and Dutch raids on Spanish towns and treasure galleons. The Spanish attempted to retake Tortuga and purge the island of the lawless den of pirates on several occasions, but Tortuga would remain in the hands of the pirates until Spain ceded Haiti, the western half of Hispaniola, to France in 1697.

The pirates of Tortuga were called buccaneers by the English, named after the buccan style of barbecuing meat. These hunters and raiders were referred to by the French as flibustiers, coopting the Dutch word vrijbuiter, or “freebooter.” The French made a distinction between flibustiers, or “filibusters,” and forbans, “pirates.”

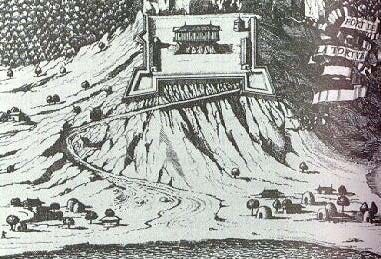

In 1640, the French sent their first colonial governor, engineer-aristocrat Jean le Vasseur, to rule over Tortuga. As soon as he arrived on the island, Vasseur hurriedly constructed the 40-cannon Fort de Rocher and hired a personal retinue of pirate bodyguards. Vasseur banned church services for Roman Catholics and built a torture device in the fort that he nicknamed “Little Hell.” From the fort, Vasseur would coordinate filibuster attacks on Spanish plantations and settlements, taking a cut of the profits for himself. In 1645, to incentivize spending on the island, he imported 1,650 prostitutes and copious quantities of wine from France. A force of 500 Spaniards dispatched from Hispaniola attempted to dislodge Vasseur in 1648. Approximately 200 Spaniards died in the ensuing bloodbath.

Under the oversight of Vasseur, Tortuga developed a common culture of equal-opportunity piracy known as the Brethren of the Coast. Before embarking on a raiding expedition, buccaneers would sign a contract agreeing upon what location they would raid, what chain of command they would follow, and how to reimburse individual pirates in the case of injuries sustained in battle. Tortuga was dubbed “the common place of refuge for all sorts of wickedness, the seminary of pirates and thieves.”

Vasseur was killed by his own henchmen in 1653. One account alleges that Vasseur abused and raped one of his lieutenant’s mistresses. A year later, an army of 800 Spaniards arrived on Tortuga, demolished Fort de Rocher, and successfully drove out the pirates. Some buccaneers continued to operate out of Tortuga, but many fled to Port Royal, Jamaica, where they ascended to the height of their power.

From 1642 to 1651, England was embroiled in a bloody Civil War between Royalist supporters of King Charles I and the supporters of the English Parliament. The Civil War resulted in the execution of Charles I and the rise of a Puritan military junta headed by Oliver Cromwell. In October 1655, Cromwell would sign a military alliance with French diplomat Cardinal Mazarin. This Anglo-French alliance was then immediately put into action with the start of the Anglo-Spanish War.

By the mid-17th century, the Spanish Empire had had over a century of time to build heavily fortified cities in Florida, Mexico, Central America, Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and South America. Attacks by English privateers and hostile natives spurred the Spanish to build walls around important ports; organize large irregular militias of conscripted natives; and sponsor naval coast guards to patrol the vast empire. The Spanish Empire was not as easy of a target as it was in the Age of Drake.

In 1654, Cromwell outfitted an armada of 30 ships and transported an army of 7,000 veterans of the English Civil War, as well as enlisted the aid of 1,000 colonial troops, with the purpose of conquering the island of Hispaniola. In April 1655, William Penn the Elder landed near Santo Domingo with an army of 4,000 men. They were immediately hit with a plague of jungle diseases and harassed by Spanish guerrillas. The invasion force lost around 1,000 men before they could arrive at Santo Domingo. Rather than put the heavily fortified city under siege, Penn order the evacuation of the army and an invasion of the lightly defended island of Jamaica. The English invasion of Jamaica was swift and resulted in few immediate casualties. The coastal Spanish planters did not offer much resistance to the English, but inland Spanish pioneers and Jamaican Maroons would wage a fierce guerrilla war for a decade.

To jumpstart the process of colonization and to protect the new English colony of Jamaica, the homeless buccaneers from the island of Tortuga were invited to reside in the new settlement of Port Royal. The buccaneers were also given privateering commissions to raid Spanish shipping and settlements legally.

In the 17th century, state-controlled navies were expensive to construct and maintain. The English Crown only operated a small navy to protect the immediate coastlines of England itself. To protect merchant ships legally, most merchants were given letters of marque (i.e., permission to attack ships belonging to nations at war with England). Letters of marque were given to trading vessels, while privateers, whose explicit purpose was to attack enemy shipping, were given “commissions for a private man-o’-war,” also known as privateering commissions. These commissions gave privateers permission to attack pirates (loosely interpreted as the Spanish coast guard) and hostile native tribes.

Some merchants were given both letters of marque and letters of reprisal. Letters of reprisal gave merchants permission from their government to steal their cargo back from an aggressor during peacetime. Sir Francis Drake was given both letters of marque and letters of reprisal during his circumnavigation of the globe as legal justification for his acts of piracy. Letters of reprisal were mostly phased out by the 1660s, but the French and Dutch still permitted letters of reprisal until the early 1700s. The tit-for-tat merchant raiding had upsides and downsides for the nations that distributed them. Dutch privateer Nicholas van Hoorn, for example, held a letter of reprisal. Van Hoorn was cheated out of the sale of slaves by Spanish merchants, so he used his letter of reprisal to justify his pillaging the Spanish city of Veracruz. In retaliation, the Spanish sacked the English Bahamas.

During the Anglo-Spanish War, Jamaican colonial governors would distribute letters of marque and privateering commissions without filling in the names of the captain and ship. Any buccaneering captain of any nation could become a legally permitted pirate on behalf of England, so long as he attacked Spanish targets. When the Anglo-Spanish War ended in 1660, the buccaneers of Port Royal would acquire or counterfeit privateering commissions from other nations that were at war with Spain. Pirates could freely outfit private warships and trade goods out of Port Royal under the commission of Portugal, the Netherlands, or even Indian tribes. In 1680, buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp was granted a commission to cut lumber in British-owned Belize. Sharp used this commission to transport 350 pirates to Central America. After acquiring a privateering commission from the chief of the Kuna Tribe, he legally attacked Spanish treasure galleons and settlements in Panama.

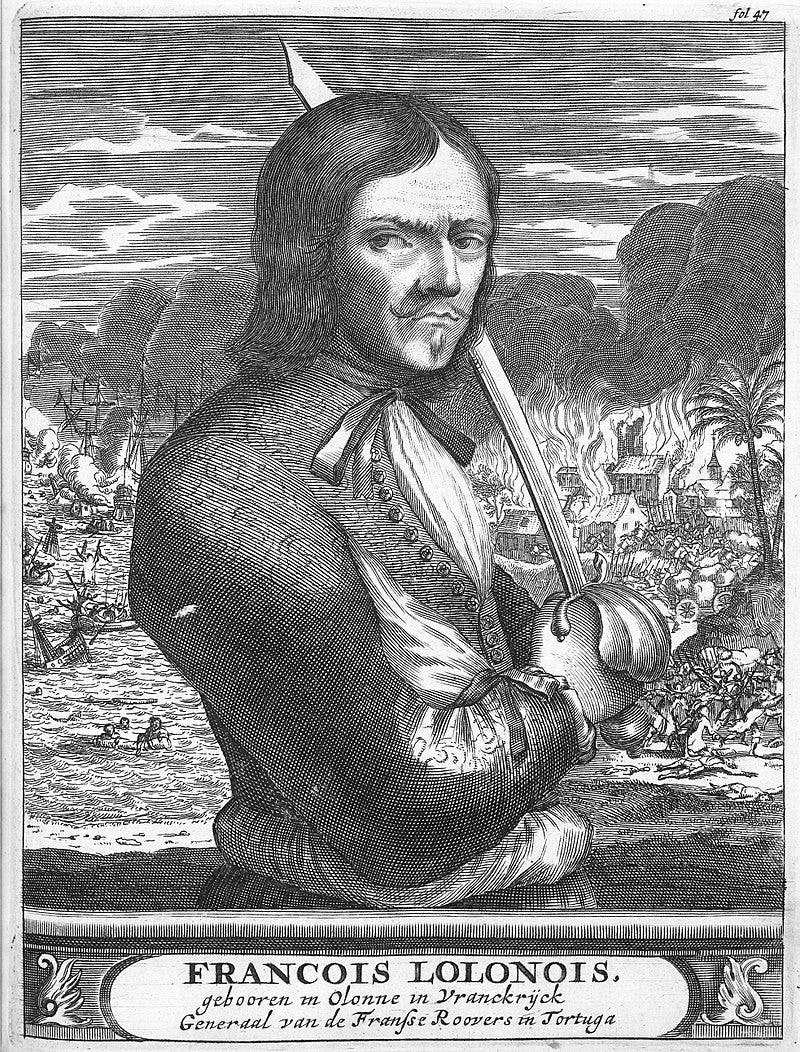

A total of over 1,500 buccaneers resided in Port Royal during the heyday of the Golden Age of Piracy. Some buccaneers were benevolent and exclusively robbed Spanish shipping. Other buccaneers were genocidal. François l'Olonnais, a.k.a. “Flail of the Spaniards,” beheaded all prisoners and frequently tortured captives. In 1663, l'Olonnais and 600 buccaneers sacked the Venezuelan city of Maracaibo, slaughtered a garrison of 500 Spaniards in the Venezuelan town of Gibraltar, and then exterminated the entire population of Gibraltar. In 1668, l'Olonnais was captured by the Spanish and was allegedly eaten alive by cannibals.

The most famous and most successful buccaneer of the 17th century was Sir Henry Morgan. Morgan was born to a wealthy Welsh family in 1635. His privateering career likely started with his participation in the Myngs Expedition. In 1663, Sir Christopher Myngs and 1,400 buccaneers raided the coasts of Central and South America, raiding Santiago de Cuba and sacking the city of Campeche in modern-day Mexico. In 1667, although England and Spain were officially at peace, Henry Morgan raided the town of Puerto Principe, Cuba. A year later, Morgan raided the city of Porto Bello and attempted to raid the towns of Maracaibo and Gibraltar, repeating the strategies of l'Olonnais. However, Maracaibo was deserted. Morgan stole every valuable he could find in the city and then ransomed the empty city for 20,000 pesos and 500 cattle. Instead of squandering his share of the loot, Morgan invested his earnings into a large sugar plantation on Jamaica and began ingratiating himself in local politics. Morgan’s last great raid was his plundering of Panama.

On January 19, 1671, Morgan led 1,400 buccaneers through the dense jungles of Panama. The men skirmished with native guerrillas, succumbed to various diseases, and quickly ran out of food. The pirates were eventually forced to eat their leather shoes rather than starve. Fortunately, the army discovered villages with provisions before they were forced to turn back. The Spanish launched a counteroffensive on January 27. A force of 1,200 Spanish militiamen and 400 lancers attacked the buccaneer army and even steered a herd of cattle in the direction of the English. Morgan chose to take a defensive position, using his sharpshooters to snipe the cattle and flanking the Spanish with a 300-man ambush. Morgan’s army surged through the three forts guarding Porto Bello. Rather than let the English loot Porto Bello, the Spanish governor set fire to the city, what was the third largest city in the Spanish colonial empire. Morgan and his drunken army of pirates raided what was left of the city and salvaged all of the gold they could find.

When Morgan returned to Jamaica, his crew accused him of hoarding gold for himself. To add to his troubles, his violation of the 1604 Treaty of London between England and Spain resulted in his indictment and incarceration in the Tower of London. A French-Dutch surgeon named Alexandre Exquemelin, whom Morgan had conscripted into his Panama invasion army, also wrote a best-selling book, History of the Buccaneers of America (1678), in which he accused Morgan of rape, torture, theft of his crew’s loot, and using nuns as human shields in the siege of Porto Bello’s forts.

Many common Englishmen supported Morgan’s more heroic deeds, so Morgan was excused of any wrongdoing, claiming to a court that he had been ignorant of any peace treaty signed between England and Spain. When asked by the court whether any Spaniard had ever told him that their nations were no longer at war, Morgan said that he would not have believed the Spanish even if they told him, as “all Spaniards are liars.” Morgan was found not guilty. He was knighted by King Charles II several days later, and then elected Governor of Jamaica. To wrap up all loose ends, Morgan successfully sued Exquemelin for libel. Morgan retired to Jamaica, where he would spend the rest of his life as the wealthy, politically influential, drunken, obese ex-king of the buccaneers. The death of Henry Morgan in 1688 marked the slow end of American piracy.

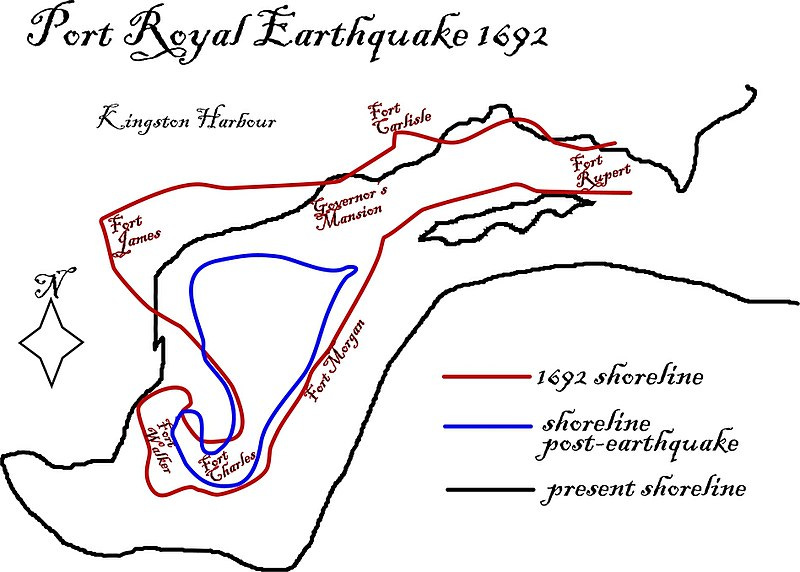

The Glorious Revolution deposed Catholic King James II and installed Protestant King William III of Orange in 1688. The new king attempted to consolidate his colonial borders by eliminating unnecessary diplomatic scandals caused by rogue privateers. In 1692, an earthquake destroyed a significant portion of Port Royal, killing around 2,000 denizens and reshaping the harbor. The main safe port for buccaneers was now destroyed, and the new William-appointed governor was no longer tolerant of violations of English peace treaties. Many colonial Whig Puritans supported smuggling out of necessity, but some Tory planters in the southern English colonies and in the Caribbean were willing to turn a blind eye to piracy committed against their hated Spanish foes.

Thomas Tew was originally commissioned as a privateer in 1694 to hunt illegal French factories in Africa. However, he went rogue and hunted shipping in the Indian Ocean. Tew used Benjamin Fletcher, the governor of Rhode Island, to fence his stolen goods. Tew would disappear somewhere around the island of Madagascar.

Henry Avery was originally hired as an officer aboard an English privateering ship, but he and 25 other men mutinied after waiting six months for the Spanish to give them a commission to attack French commerce; furthermore, his English company refused to pay the crew their wages due. Avery sailed his large pirate man-o’-war into the Indian Ocean and looted a heavily-armed Mughal hajj pilgrimage fleet. The wealth that Avery’s crew captured was so great that it caused a diplomatic incident between the Mughal Empire and the English, triggering the first international manhunt for Avery. Avery quietly slipped past authorities, dumped his ship at the port of Nassau after bribing the governor of the Bahamas, and disappeared in 1695.

After failing to catch any pirates as a pirate-hunting privateer, William Kidd turned to piracy. He raided an Armenian merchant vessel laden with valuable goods in 1698. Kidd tried to fence his goods in New York City and stashed some of his treasure on Gardiners Island. One of Kidd’s original investors, Richard Coote, governor of New York, lured him to the town by promising him clemency for his acts of piracy. Instead, Coote imprisoned Kidd and shipped him to London, where he was found guilty of piracy and hanged. English pirates were quickly being hunted down rather than overlooked and employed.

In 1701, the War of Spanish Succession had kicked off in Europe, and England opportunistically intervened. The English front of the war is commonly known as Queen Anne’s War.

By 1700, the American Eastern Seaboard was mostly consolidated by English colonies, with the only points of contention being the border between English South Carolina and Spanish Florida and the border between English Massachusetts and French Quebec. Queen Anne’s War led to several battles over these two borders.

After the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, privateers were quickly out of work again. However, some English privateers wished to continue the fight against the Spanish.

The Pirate Commonwealth of Nassau

Benjamin Hornigold was an elderly veteran of Queen Anne’s War and the son of a pious Puritan family. Rather than finding employment as a merchant, he wished to continue raiding Spanish sea commerce because the Spanish coast guard had not stopped harassing English commerce, in spite of the Treaty of Utrecht. He made his base of operations Nassau, a tiny island in the Bahamas inhabited by roughly 100 Puritan colonists from Barbados.

In 1715, a Spanish fleet of treasure galleons sank off the coast of Florida, sparking a gold rush of treasure-hunting divers. Pirates stationed in the Bahamas quickly took notice and preyed on the divers.

Between 1713 and 1716, under the “protectorship” of Hornigold, Nassau was transformed from ghost town to a loose confederation of roughly 1,000 pirates known as the Flying Gang. The exploits of these Flying Gang pirates were immortalized in history in the two volumes of A General History of the Pyrates. Virtually every aspect of pirate mythology comes from this one book. Although a significant number of Pyrates are romanticized in fiction and the illustrated portraits of the pirates featured clothing popular in 1730s London rather than 1710s Caribbean, much of the contents can be verified with the court testimony of the many pirates and former pirates of the Flying Gang.

The economic model of the pirates worked as follows:

Captain Hornigold would plunder Spanish ships.

Hornigold would fence his goods to his merchant friends John Cockram and Richard Thompson.

Cockram and Thompson would sell their illegally acquired goods in Charles Town, South Carolina.

Cockram and Thompson would buy food and provisions in Charles Town and sell them in Nassau to hungry pirates.

In the spring of 1716, commissioned privateer Henry Jennings arrived in Nassau. Unlike Hornigold, Jennings was politically a Jacobite. (Jacobite was a term used to describe the supporters of the deposed King Charles II.) Jennings had no qualms about raiding English shipping, seeing as though England was ruled by an illegitimate king. Rather than fencing goods in South Carolina, Jennings used his contacts in Jamaica to fence his own goods.

Few, if any, of the Flying Gang pirates self-identified as outlaws or pirates. The minority of the Flying Gang were Puritan-leaning privateers who saw themselves as agents in a Protestant project stretching back to Sir Francis Drake and Sir Henry Morgan, continuing the fight against the Spanish Catholic tyrants. Hornigold saw Nassau as an investment rather than a get-rich-quick scheme and went out of his way to attack Spanish ships transporting grain to feed Nassau. These pirates would fly the Union Jack alongside the Jolly Roger. These pirates included Hornigold, Cockram, Thomas Tew, William Dampier, and Black Sam Bellamy.

On the other side of the pirate political spectrum, the majority of the Flying Gang were Jacobites who flew St. George’s Cross alongside the Jolly Roger. These pirates were Irishmen and Scotsmen, planters from Bermuda and Jamaica. They had profited under the deluge of Stuart privateering commissions and wished to return to that status quo. These pirates included Jennings, Edward England, Blackbeard, Stede Bonnet, Charles Vane, and Calico Jack Rackham.

Unlike the buccaneers of old, the Flying Gang had relatively small crews and preyed on lightly armed merchantmen rather than cities or galleons. While it is said that Black Bart Roberts was the most successful pirate of all time for capturing over 400 ships, the vast majority of his prizes were small fishing ships.

The Jacobite pirates quickly began to damage British trade. In September 1717, the British government sent a fleet of seven ships carrying 100 soldiers and 130 colonists headed by Woodes Rogers. Before convincing the British government to grant him governorship of the Bahamas, Rogers circumnavigated the globe as a commissioned privateer alongside pirate William Dampier during the War of Spanish Succession and was facially deformed from wounds he sustained in battle. After being sued into near-bankruptcy by his former privateering venture investors, Rogers lived off of the royalties from his best-selling memoirs.

As the new governor, Rogers offered the pirates an ultimatum: accept a royal pardon for their acts of piracy, or declare themselves outlaws. The vast majority of the pirates wanted either to avoid becoming outlaws hunted by their countrymen or to buy themselves enough time to outrun the Royal Navy, so they accepted the pardons. Only diehard political dissidents such as Charles Vane did not accept the pardon and actively fought Governor Rogers. Blackbeard and Black Sam accepted the pardons but then sailed north to raid the Carolinas and New England. Some pirates such as Edward England sailed to Madagascar to raid in the Indian Ocean. Most active pirates were hunted down to a man by the British Royal Navy or perished at sea.

A year after Rogers quelled the pirates of Nassau, the War of the Quadruple Alliance reinvigorated the need for commissioned privateers. With the death of Bartholomew Roberts at the hands of the Royal Navy in 1722, the Golden Age of Piracy was over. The United Kingdom established a large formal navy, and the colonial borders in the Caribbean had solidified. The old buccaneers of Port Royal became sugar planters. Even the old pirates of Tortuga settled down and built their own sugar plantations on the newly conquered French colony of Haiti.

Woodes Rogers, the man who tamed the pirates, sailed with the pirate William Dampier. Dampier sailed with buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp. Sharp sailed with the greatest buccaneer Henry Morgan. Morgan learned how to raid from feral French, Dutch, and English hunters. The direct continuity of the pirate profession ended with Rogers. The term “filibuster” fell out of use for over a century… until Americans revived it.

Early American Pirates and Patriots

From their inception, the Thirteen Colonies encouraged smuggling, counterfeiting, piracy, ship-salvaging, and territorial expansion. Merchants based in New England smuggled Spanish and French molasses into their ports against British mercantile law. The southern colonies regularly harbored pirates and fenced their ill-gotten goods. The western frontier beyond the Appalachian Mountains was a contentious and lawless warzone for the majority of the 18th century.

The Washington family was involved in both the frontier wars and Caribbean wars. George Washington’s older half-brother Lawrence Washington fought under Admiral Edward Vernon in the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Lawrence fought in the British invasion of modern-day Colombia, Panama, and Cuba, growing attached to the Admiral under whom he served. Lawrence would later name his plantation Mount Vernon after his superior officer. George would inherit Mount Vernon following Lawrence’s untimely death. During the War of Jenkins’ Ear, the colony of Georgia attempted to march a small army to seize St. Augustine, a Spanish-held fort in Florida, but failed. This was neither the first time nor the last time that America would invade Florida.

Over a decade after Lawrence fought under Admiral Vernon, George Washington served during the French and Indian War, notably in the 1755 Braddock Expedition, a disastrous attack mounted against French-occupied forts in the Ohio Valley.

The French and Indian War concluded with the British occupation of the Ohio River Valley west of the Appalachian Mountains. However, American colonists were forbidden from settling in the valley by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The British government wanted to assure Indian tribes that colonists would not continue to expand westward at their expense. This, of course, did not stop trailblazers like Daniel Boone from illegally establishing fortified settlements west of the Appalachians in violation of the Royal Proclamation.

The coastal regions of the Thirteen Colonies were consolidated under large estates, leaving very little land for smaller-scale planters, subsistence farmers, and new Scots-Irish immigrants. In response to the dearth of land in the east, poorer settlers pushed into the lawless west. In the foothills of the Appalachians, colonial governments had little to no judicial control over the settlers. There were several small-scale revolts against incompetent, corrupt, and over-extended legal authorities, most notably in the Regulator Revolt in North Carolina.

American Colonial prosperity was throttled by Great Britain’s mercantile economic policies, frontier border control, and aloof British-appointed governors, resulting in the American Revolution.

To conduct war against the mighty Royal Navy on the high seas, the Continental Congress passed an act on March 23, 1776, to begin distributing privateering commissions and letters of marque. The newly independent United States of America did not have any formal warships, so they heavily relied on commerce-raiding privateers to capture British supply ships carrying arms, ammunition, and provisions. Around 800 American merchant vessels were commissioned as privateers. Many captured neutral vessels which had to be returned to their owners. Over the course of the war, American privateers captured or destroyed roughly 600 British ships.

The Peace of Paris ended the American War for Independence in 1783 and consolidated the borders of the new nation. The United States Congress then signed the Neutrality Act of 1794, which forbade American non-state actors from conducting formal diplomacy with other countries and prohibited American ports from equipping foreign warships in their harbors.

In spite of the legalization of American settlement west of the Appalachians, many American politicians wanted to acquire even more lands west of the Mississippi, annex British-held Canada, and annex Spanish-held Florida and Louisiana. These expansionists were predominantly southern and western Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans. The administrations of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe attempted to buy and coerce their territorial neighbors into giving up their colonial possessions.

The Jeffersonians were opposed by New England Federalists, and later the Whigs, who wanted to consolidate the newly acquired American frontiers rather than agitate European foreign powers with more territorial acquisitions. These pacifistic Puritans were led by John Adams and later by his son John Quincy Adams.

Foreign ownership of Louisiana was a national security concern for the young United States. Although Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795 granted the United States ownership of the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, a vital shipping route for trade west of the Appalachian Mountains, Spanish governors of New Orleans frequently threatened to stop all trade coming out of the mouth of the river. Spain revoked the treaty in 1798, and Americans could not trade in New Orleans until 1801, when Napoleonic France acquired New Orleans in the Treaty of Aranjuez. Under the treaty, Spain would govern the territory on behalf of France.

On October 16, 1802, the Spanish intendant of New Orleans, Juan Ventura Morales, closed the port to all American commerce. Although the Spanish King Charles IV disavowed and reversed Morales’s actions, the American Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith asked Congress to permit him to send a naval invasion to take New Orleans by force. America was a young nation with a navy of only a dozen warships, but it fully intended to use them in conquest against hostile European powers. In July 1803, Thomas Jefferson purchased from cash-strapped Napoleon the French territory of Louisiana, 530 million acres of sparsely populated land, for three cents per acre.

Jefferson unconstitutionally acquired this land without the explicit permission of Congress, generating consternation from his Republican allies and Federalist foes. Although the Purchase granted America ownership of the entire Louisiana water basin, there were several areas of contention, including parts of the Spanish Florida Panhandle to Louisiana’s east and Texas to Louisiana’s west.

To the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans, it was a matter of national security to acquire all of the waterways from the mouth of the Mississippi River to Florida to prevent the malicious Spanish from strangling American trade. As Jefferson would later say:

[Napoleon] ought the more to conciliate our good will, as we can be such an obstacle to the new career opening on him in the Spanish colonies. that he would give us the Floridas to withold intercourse with the residue of those colonies cannot be doubted. but that is no price; because they are ours in the first moment of the first war, & until a war they are of no particular necessity to us. but, altho’ with difficulty, he will consent to our recieving Cuba into our union to prevent our aid to Mexico & the other provinces. that would be a price, & I would immediately erect a column on the Southernmost limit of Cuba & inscribe on it a Ne plus ultra as to us in that direction…

I thank you for the Squashes from Maine. they shall be planted to day. I salute you with sincere & constant affection.

The Spanish Empire was crumbling. Napoleon successfully conquered Spain in 1808 and installed his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne. The lack of oversight from the home country was seen as an opportunity for Spanish liberals in the Americas to revolt. Rebels in Mexico, Colombia, Chile, and Peru rose up against their colonial overlords in a 25-year struggle for independence. Many Spanish rebel leaders, such as Colombian revolutionary Simón Bolívar, modeled themselves after American Revolutionaries.

Many American and British filibusters and mercenaries sailed south to assist the rebels in overthrowing the Spanish. In exchange for their service in the liberal revolutionary armies, these Anglo-American mercenaries were promised land grants and titles by rebel leaders. One such American filibuster was William Stephens Smith, the brother-in-law of John Quincy Adams. Smith and 200 other filibusters joined the revolutionary army of Francisco de Miranda to liberate Venezuela in 1806. Smith’s ships were intercepted by the Spanish before they could invade. Smith was then sent back to America, where he was found not guilty of violating the Neutrality Act of 1794. Smith would later have a successful career as a Federalist congressman.

A significantly more successful filibuster was Scotsman Gregor MacGregor. MacGregor was an officer in the British army during the Napoleonic Wars, but he saw little action, as he was garrisoned in England and Gibraltar, and he had proved himself to be a hindrance to the Portuguese army in the Peninsular War. Seeking fame and fortune, MacGregor became a brigadier general under Simón Bolívar, fighting for Venezuelan and Colombian independence, where he distinguished himself in a bloody Fabian scorched-earth retreat against a superior Spanish loyalist force in 1816.

Seeing weakness in Spanish foreign policy, privately funded armies of American militias attempted to topple Florida’s corrupt Spanish government and secure America’s waterways.

The Ballad of Three Floridas

By the early 1800s, hundreds of Americans began to populate the sparsely populated region of West Florida, an area still controlled by the Spanish east of New Orleans in modern-day Louisiana.

Spanish Florida was legally corrupt — irregularly cutting off inland trade to the Gulf of Mexico, permitting runaway American slaves to sanctuary, and allowing Indian tribes hostile to American settlers to set up bases from which they could organize raids against American plantations.

Spanish Florida was administered by alcaldes, a municipal position that functioned as a judge and mayor. The alcaldes west of New Orleans were notoriously corrupt in civil cases, favoring whichever party could offer the largest bribe. They used their government positions to enrich themselves at the expense of other settlers. They were often the largest landowners in their respective regions.

While Spain refused to sell Florida to the United States, rumors abounded of a British invasion of Pensacola, and the Federalists were still enraged by the unconstitutionality of the Louisiana Purchase. To circumvent official diplomatic channels, President Madison encouraged American landowners to revolt against Spain in West Florida.

At four o’clock on Sunday morning, 23 September 1810, eighty armed Americans commanded by Philemon Thomas stormed the dilapidated Spanish fort in Baton Rouge, West Florida. As the invaders streamed through the undefended gate and gaps in the stockade and past the unloaded cannon, they demanded that the Spanish troops surrender their weapons. Don Louis Antonio de Grand-Pre, commander of the bastion, bravely resisted as his few ill-equipped and invalid soldiers conceded. Other than the brave young leader and Manuel Matamoros, who died defending their honor and the Spanish flag, there were no other casualties. Governor Carlos De Lassus, abruptly awakened by the screaming and gunshots, quickly dressed and hurried toward the fort. But before he had traveled the block from his house to the scene of the activity, rebel horsemen overwhelmed and captured him. With the governor’s apprehension, the conquest of Spanish Baton Rouge had ended in a matter of minutes.

Frank L. Owsley, Jr., and Gene Allen Smith. Filibusters and Expansionists: Jeffersonian Manifest Destiny, 1800–1821 (University of Alabama Press: 1997).

In late September, local American landowners hastily assembled a governing legislature. On November 9, 1810, they elected Fulwar Skipwith as governor of the independent State of Florida. Skipwith ardently argued that his new nation should remain separate from the United States. Skipwith hurriedly swept through the rest of West Florida, clearing out the remaining Spanish garrison, and reinforcing Baton Rouge for the impending Spanish counteroffensive.

Upon hearing the news of the filibuster, President Madison dispatched Louisiana Governor William Claiborne and 300 American soldiers to annex West Florida. Skipwith initially refused Claiborne’s offer, barricading himself in Fort San Carlos, Baton Rouge. Skipwith surrendered to Claiborne on December 10, 1810. The Republic of West Florida only lasted for two and a half months.

By the time the East Floridians were pacified by the governor of Louisiana, President Madison organized a covert filibustering mission to seize northeastern Spanish Florida under General George Matthews. Eastern Florida was used as a naval base for British warships, adding to already strained diplomatic relations between America and Britain. Meanwhile, desolate and thinly populated Spanish Florida was used as a base by hostile Seminole Indians and escaped slaves.

On January 15, 1811, Congress passed a secret act commissioning General Matthews and Colonel John McKee to seize Florida if Britain attempted to occupy it. Matthews preemptively hired a force of 250 Georgian militiamen and began marching them to St. Augustine. Matthews’s army successfully occupied a fort on Amelia Island, Florida, and continued to march southward, raiding local towns as they went. The invaders positioned John McIntosh as the new state’s director and shabbily assembled a temporary municipal government. This breach of diplomatic relations caused Secretary of State James Monroe to recall Matthew’s men. This campaign would later be called the Patriot War.

Fighting along the Florida border between American militias and native tribes continued and intensified. In 1816, General Andrew Jackson and two gunboats attacked a fort containing hostile Creek Indians and fugitive slaves located in Spanish Florida. In the ensuing battle, Jackson’s gunboats fired at the “Negro Fort” and hit the fort’s gunpowder storage room, causing the fort to blow up in a fiery inferno.

A year later, in 1817, Latin American war hero Gregor MacGregor would attempt to mount a second filibuster of East Florida. MacGregor convinced approximately 150 veterans of the War of 1812 to assist him in invading Florida. To raise money for arms, MacGregor would sell land bonds for his future nation to Americans in Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia.

MacGregor and his filibuster army invaded Florida in June 1817. MacGregor had preemptively sent a spy to Fort San Carlos at Amelia Island, bluffing that MacGregor was leading an army of 1,000 Americans. When MacGregor finally arrived at the fort, most of the surrounding towns were already abandoned, and the fort surrendered without a fight. The Spanish governor would execute the fort’s garrison commander for his cowardice.

Rather than marching south as General Matthews had done, MacGregor and his men drank copious amounts of alcohol and fell into a stupor. MacGregor refused to pay his men in real currencies and did not have the manpower to seize any other towns, so the filibuster army began to dissemble. Several officers and men deserted, and on September 6, 1817, MacGregor stole one of his own ships and abandoned his new republic.

In 1818, Andrew Jackson invaded Florida again, attempting to fight Seminole Indians. Two British merchants were caught in the crosshairs of Jackson’s invasion: Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot. Jackson had the two men court-martialed and executed for arming hostile Indians. This diplomatic incident was recounted by former President Thomas Jefferson:

It is of great consequence to us, & merits every possible endeavor, to maintain in Europe a correct opinion of our political morality. these papers will place us erect with the world in the important cases of our Western boundary, of our military entrance into Florida, & of the execution of Arbuthnot and Ambrister. on the two first subjects it is very natural for an European to go wrong, and to give in to the charge of ambition, which the English papers (read every where) endeavor to fix on us.

Spain sold its territories in Florida to the United States on February 22, 1819, in the Adams-Onis Treaty. Congress also passed the Neutrality Act of 1818, formally putting an end to two decades of American filibustering by the penalizing filibusters with a three-year prison sentence.

While the Florida Question was resolved, Louisiana’s western border was left open. Although the Adams-Onis Treaty granted America the territory of Florida, the treaty also forced America to abandon its claim to eastern Texas. In the same letter Jefferson sent to Monroe congratulating him on the acquisition of Florida, he suggested that the next territory that needed annexation was Spanish Texas:

I propose then that you select mr Adams’s. principal letters on the Spanish subject, to wit, that which establishes our right to the Rio-bravo which was laid before the Congress of 1817.18. his letters to Onis of July 23. & Nov. 30. and to Erving of Nov. 28.

In the 1810s, Mexico waged a costly war of independence against Spain, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Mexicans. In the chaos of the war, Mexican Texas was subjected to several battles as well as raiding from the Comanche horsemen of the Great Plains. To an enterprising American filibuster named James Long, Texas was ripe for the taking.

James Long, along with over 200 men — mostly Mississippians — and James Bowie, marched through eastern Texas to the town of Nacogdoches, where he established a state capital and 12-men governing council. While Long attempted to provision his army by setting up a trading port at Galveston, his army was pushed out by an army of 500 Spanish colonial troops. Long fled back to Louisiana but was unperturbed. Long launched a second invasion of Texas in September 1821 with only 52 men. In less than a month, he was defeated by a local Spanish garrison and executed.

The failures of the Long Expeditions would not put off American expansion into Texas. The Mexican government would eventually gain its independence from Spain, and American settlers in Texas did eventually lead a successful revolution against Mexico, as explained by Old Glory Club during Alamo Day.

Aggressive territorial expansion radicalized many northern Whigs. The Whig Party, led by John Quincy Adams, opposed America’s jingoistic provocations and warmongering aimed at Mexico. On April 16, 1838, Adams delivered a speech to Congress against the annexation of the Republic of Texas:

Because it is a flagrant violation of the Laws of Nations. The insurgents with arms and ammunition, marched openly from the United States and seized on the territory and slaughtered the loyal citizens of Mexico, with whom we had treaties of peace and amity, that should have been held sacred.

Because this forcible seizure of Texas is avowedly an entering wedge to an extended series of conquest, rapine and oppression, to overpower the free States, and make an undue preponderance against them, particularly in the election of the Senate and Executive, by indefinitely extending the Slave Representation, infinitely the most unjust and infamous system ever recognized by any nation, civilized or barbarous, in the whole annals of the globe. Not content with the increase of the 70,000 innocent human beings annually born in this “free republic” to no inheritance but that of slavery, this odious slave power seems desperately bent on trampling on the rights and liberties of our peaceful neighbors, and forcing its evils and horrors within their borders, to open new markets for its hapless victims, and overbalance the remaining power of the yet free States.

Because there is no shadow of pretense of any constitutional power whatever to annex a foreign nation, but such an act would be in open defiance both of the entire letter and spirit of the Constitution; that instrument provides for such emergencies, and prescribes the forms of amendment, and it is only by an alteration of the constitution, ratified by the legislatures or the people of three-fourths of the States, that such a change can be effected. If the annexationists really believe that the people of the U. S. will sanction their schemes, why do they not test them constitutionally?

Adams’s arguments stalled Congress’s annexation for only six years. The surge of westward expansion was not assuaged by the supposed unconstitutionality of annexing entire nations.

The Filibuster Wars

The term “Manifest Destiny” was coined by John O’Sullivan, a journalist and propagandist for the great American filibusters of the 1850s. This concept embodied the Jeffersonian ideal of yeoman American agrarians expanding westward, bringing with them the virtues of American democratic-republicanism. Free men in a free market enriching themselves.

In the election of 1844, James K. Polk, the Democratic Party frontrunner, promised three territory acquisitions. He promised the acquisition of the Oregon Territory at the 54-degree, 40-minute latitude line with the slogan “54-40 or fight,” a veiled threat that America would go to war with Britain if Americans could not settle just south of the 54-40 line. Polk promised to acquire the port of San Francisco to appease mercantile Whigs who wished for America to gain a Pacific port. Lastly, Polk promised the annexation of Mexican land west of the newly added State of Texas to appease Southern Democrat expansionists.

Polk would achieve all three of these goals in his two terms as president. He peacefully signed the Oregon Treaty of 1846, granting America the Oregon Territory south of the 49-degree latitude line. Polk then waged the successful Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848, forcing Mexico to cede the territory from Texas to California for the discounted price of $15 million. In the fervor of American expansionism, a new wave of filibusters emerged out of the American West. Between 1850 and 1854, American land pirates set their eyes on Mexico’s Baja California and Sonora territories, Cuba, and Nicaragua in the Filibuster Wars.

Narciso López was born in 1797 to a family of wealthy Venezuelan planters. His kin, who owed their status to the patronage of the Spanish Crown, were ousted by Bolivarian revolutionaries. López found himself in Cuba, where he ingratiated himself with Cuban planter society. While López grew into adulthood, Cuba faced the most violent slave revolt in its history. Many Cuban planters accused British Abolitionists, such as David Turnbull, and British military intelligence of instigating the slave revolt and arming the slaves. In the mid-19th century, the Spanish government began toying with the notion of eventually abolishing slavery in the Spanish Empire at the behest of the British government. This shift resulted in some Cuban slave owners turning to agitating for Cuban independence or American annexation because of America’s extensive history of putting down slave revolts.

Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic-Republicans believed in the long-term project of Cuban annexation. As Jefferson wrote to Madison in 1809:

I presume the expediency of pursuing her by a swift sailing dispatch was considered. it will be objected to our recieving Cuba, that no limit can then be drawn for our future acquisitions. Cuba can be defended by us without a navy, & this developes the principle which ought to limit our views. nothing should ever be accepted which would require a navy to defend it.

In 1849, Narciso López began to campaign for a filibustering expedition to free Cuba from the yoke of their oppressive Spanish overlords. López was promoted through partisan Democratic Party newspapers by John O’Sullivan and funded by several governors and prominent politicians, such as Governor John Quitman and Senator John Henderson. López promised to sell these men public land owned by the Cuban government in exchange for cash. López also used American and Cuban Freemasonic lodges to network with potential benefactors.

Many Southern Democratic politicians saw the opportunity to add one more pro-slavery state to the Union as a political boon. Senator Jefferson Davis from Mississippi supposed that Cuba could have been broken into two or three pro-slavery states. Davis assisted López in identifying potential generals to lead the filibustering expedition. His first suggestion was Mexican-American War veteran Major Robert E Lee. Lee politely declined López’s offer, and López opted to lead his invasion himself.

Although Louisiana and Cuba both grew sugar on vast plantations and they would have competed with each other on the American sugar market, López recruited many working-class adventurers from New Orleans. López was able to recruit many filibusters from Charleston, South Carolina, and some Free Soil Party activists from the north.

López and his 600-man army of filibusters invaded Cuba in September 1850. They quickly seized the city of Cardenas, facing little resistance from the city’s garrison. López expected to find local networks of planters to rally around his independence army. Instead, as soon as López’s men began raiding local farms for supplies, the populace turned on López. Facing an impending counterattack from the Cuban army, López boarded his filibuster steam ship and made it to the American Florida Keys before the Spanish navy could catch him. López was federally indicted for filibustering but found not guilty. López was met with significant fanfare from the American press.

In August 1851, López attempted to launch a second expedition to liberate Cuba. This time, López could only manage to hire 425 men, predominantly German and Hungarian exiles. Newspapers had been feeding stories to López of a successful rebellion kicking off in southern Cuba, so López expedited his second invasion. When López arrived, the local insurrection was already put down. The Cuban government spotted López’s ship before he landed, so the local Cuban militias were prepared. López’s army was ambushed by Cuban government forces and then retreated into the Cuban jungles. The mercenaries eventually starved, and were surrounded and captured. López was executed along with his men. One of López’s filibusters, William Logan Crittenden, the nephew of U.S. Attorney General John Crittenden, wrote before his execution:

Dear Uncle: In a few moments some fifty of us will be shot. We came with López. You will do me the justice to believe that my motive was a good one. I was deceived by López — he, as well as the public press, assured me [that] the island was in a state of prosperous revolution.

I am commanded to finish writing at once.

Your nephew,

W.L. CrittendenI will die like a man

Upon hearing of the failed second filibuster invasion of Cuba, President Franklin Pierce intended to fund a more thorough covert filibuster if Spain continued to refuse to sell Cuba to America. However, the issues of slavery and Bleeding Kansas erupted, distracting the president from territorial expansion schemes.

A month after López’s execution, John Quitman and John Henderson, López’s largest financial backers, formed the Order of the Lone Star. This organization was a fraternal order and political interest group whose purpose was to incorporate Cuba as an American state. At the height of its popularity, Lone Star had 50 chapters in 8 states and an estimated membership of 20,000 men.

Joseph C. Morehead was a lawman in California in the 1840s. In 1849, he led an expedition to punish the Yuma Indians in retaliation for the Glanton Massacre. Morehead recruited 142 men to raid Yuma crops and destroy their villages. The cost of the expedition nearly bankrupted the State of California. In April 1850, Morehead and 300 men marched from Los Angeles and San Diego to invade Baja, Mexico. On May 26, several men claiming to have been part of the filibuster force passed through Los Angeles, claiming Morehead was en route to coup the government of Sonora, Mexico. The ship transporting the filibusters allegedly stopped at the Mexican port of Mazatlán. The filibusters were never seen again.

William Walker was born in 1824 to poor Tennessee settlers. From a young age, Walker was identified as a child prodigy, and he graduated summa cum laude at the age of 14 and then became a doctor at the age of 19. The death of his fiancée Ellen Martin disturbed him and disenchanted him from the medical profession. Walker soon took to studying law and politics.

In 1849, Walker moved to San Francisco and became the editor of a Free Soil Party political newspaper. Similar to many Americans in the West, Walker was ambivalent about the issue of slavery but passionately supported American expansion into new territories. The Morehead Expedition to seize Sonora disappeared, so Walker proposed an expedition to Baja California and then an overland march to Sonora.

On October 15, 1853, the 5′1″ “Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny” William Walker and 45 filibusters began marching to Baja, Mexico. The men easily captured the tiny town of La Paz and declared independence from Mexico. Word of Walker’s new Republic of Lower California quickly reached San Francisco, and the locals outfitted a ship full of reinforcements and provisions. After 250 more men arrived at La Paz, Walker and his filibuster army marched eastward to seize Sonora while leaving a small garrison behind in his capital. Walker would not reach Sonora. Instead, he was turned back after running out of supplies and being ambushed by Apache Indian raiders. Meanwhile, local Mexican landowners south of La Paz assembled a large militia, which forced Walker out of Baja California. Walker was president of the Republic of Lower California and Sonora for eight months.

When Walker returned to California, he was indicted by the federal government for violating the Neutrality Act via filibustering. Walker was acquitted by a sympathetic jury after only eight minutes of deliberation. Walker was not dissuaded by his failed first expedition. In 1855, Walker would topple the government of Nicaragua.

Throughout the early 19th century, the country of Nicaragua was embroiled in a national struggle between the liberal Democratic Party located in León and the conservative Legitimist Party located in Granada. In 1854, Nicaragua held national elections for the Supreme Director of Nicaragua. The Democratic Party candidate lost the election, accused the Legitimists of election fraud, and all Democratic politicians refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Legitimist government. Democratic Party President Francisco Sanabria opted to hire the services of William Walker to import 300 American “colonists.” On May 3, 1855, William Walker and 60 mercenaries set sail for Nicaragua.

Walker assumed control over the Democratic Party’s militia and marched his army to war with the Legitimists. In spite of being vastly outnumbered and running critically low on supplies, Walker tipped the balance of the Nicaraguan Civil War in the decisive Battle of La Virgen. The mercenary army pressed deeper into Legitimist territory, confiscating American industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt’s steamships to use to capture the Legitimist capital at Granada. Walker then used his Democratic Party puppet Patricio Rivas to consolidate his rule. American Democratic President Franklin Pierce recognized the legitimacy of Walker’s regime on May 20, 1856. A Democratic Party national election was then held, and William Walker was nominated President of Nicaragua. Several of his mercenary comrades were given official positions in the Nicaraguan government as well. As President, Walker legalized slavery and made English the official language of the Nicaraguan government. Walker had reached the zenith of his power and influence.

While Walker organized his new government, agents of Cornelius Vanderbilt began arming mercenaries in Costa Rica, the country immediately south of Nicaragua. Vanderbilt had sunk large quantities of money and manpower into securing a steamship transportation monopoly on Lake Nicaragua and had backed the Legitimist Party during the brief civil war.

Walker preemptively invaded Costa Rica in March 1856 but was immediately defeated at the Battle of Santa Rosa. Vanderbilt’s mercenary army pushed north as Walker reeled from the loss of the first battle of the Filibuster War. On Nicaragua’s northern border, the countries of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala built a coalition army backed by British industrialists who wished to recoup their Central American investments from Walker. In the Nicaraguan heartland, the Democratic and Legitimist Parties forged an alliance and rallied a united militia army to oust the American mercenary menace.

Rather than see the Legitimists retake his capital, William Walker had the city of Grenada burned to the ground before he surrendered to Commander Charles Davis of the American Navy. Walker spoiled any goodwill he had in America by blaming his defeat on the lack of support he received from the American military.

While Walker invaded Nicaragua, Henry Crabb launched the final filibuster expedition against Sonora, Mexico. Crabb was a pro-slavery Whig Party activist and rapid expansionist. From 1857 to 1861, Mexico waged a civil war known as the Reform War, pitting wealthy conservative landowners and the Catholic clergy against anti-clerical liberal land reformers. To assist in his revolt against the conservative government, Sonora’s rogue liberal governor Ignacio Pesqueira invited 1,000 American colonists *cough* *mercenaries* *cough* to settle in Sonora to tip the province’s balance of power in the liberal coalition’s favor. Henry Crabb accepted Pesqueira’s offer and recruited 100 men to invade Sonora. By the time Crabb arrived in Sonora, Pesqueira had already defeated his Mexican conservative foes and had no need for American filibusters. Rather than politely asking Crabb to leave, Pesqueira ordered his army of 1,200 men to massacre the filibusters. Out of the 100 American filibusters, only 13 would make it back across the border.

Machines, Marines, and Men in Black

The abject failure of American filibusters in the 1850s and the Civil War killed the notion that Manifest Destiny could be delivered by filibusters. Americans could invest in Latin American plantations, mines, and transportation — they could even volunteer to fight in Latin America as mercenaries — but the idea of a private army composed of irregular militiamen toppling governments was dead.

A Confederate exile such as Major Edward Austin Burke could flee to Honduras and make a name for himself as a regional warlord, but he could never rule Honduras in his own right. American adventurers could fight for political factions in Ecuador, Canada, Hawaii, and Mexico as private military contractors, but they could never again hope to repeat the West Florida filibuster or Texas Revolution.

The American Military-Industrial Complex neutered the Spanish Empire in the Spanish-American War in 1898. The American government had no need for scrappy cowboys with shotguns running roughshod in the Mexican desert; the American government after the Civil War could dispatch its own Army cavalry units. The López Expeditions were not repeated with another abortive private militia invasion; it was repeated with the abortive CIA-backed Bay of Pigs invasion.

The idea of American filibusters in the twenty-first century is farcical and takes the form of Operation Red Dog. In 1981, the Caribbean island of Dominica elected a Communist government and deposed its prime minister. To retake his lost position, former Dominican Prime Minister Patrick John and Texan mercenary Mike Purdue used proxies in the U.S. federal government, at the behest of the CIA, to recruit a motley crew of Neo-Nazis, Ku Klux Klansmen, and white supremacists to retake the island.

Operation Red Dog was foiled by the ATF. On April 25, 1981, three FBI agents busted the nine men on a yacht at a New Orleans marina. Implicated in the conspiracy were former KKK Grand Wizard David Duke, former Texas Governor John Connally, and Congressman Ron Paul.

The practicality of filibustering is over, but the legends still live on in media. In the critically acclaimed 1985 novel Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, the protagonist is recruited by Captain White, a filibuster captain whose aim is to conquest Sonora, Mexico. Captain White laments America’s refusal to annex Mexico after the Mexican-American War and then gives his justification for filibustering:

We fought for it. Lost friends and brothers down there. And then by God if we didn’t give it back. Back to a bunch of barbarians that even the most biased in their favor will admit have no least notion in God’s earth of honor or justice or the meaning of republican government. A people so cowardly they’ve paid tribute a hundred years to tribes of naked savages. Given up their crops and livestock. Mines shut down. Whole villages abandoned. While a heathen horde rides over the land looting and killing with total impunity. Not a hand raised against them. What kind of people are these? The Apaches won’t even shoot them. Did you know that? They kill them with rocks…

What we are dealing with… is a race of degenerates… There is no government in Mexico. Hell, there’s no God in Mexico. Never will be. We are dealing with a people manifestly incapable of governing themselves. And do you know what happens with people who cannot govern themselves? That’s right. Others come in to govern for them.

Wherever there are lawless frontiers, there will always be privateers, buccaneers, pirates, and filibusters.

![The Habsburg Empire of Charles V, the first “Empire on which the sun never sets”.

[[MORE]]Charles V, essentially a political product of Austria’s marriage policies to create a universal monarch. Born in 1500 in the Flanders to Philip the Handsome... The Habsburg Empire of Charles V, the first “Empire on which the sun never sets”.

[[MORE]]Charles V, essentially a political product of Austria’s marriage policies to create a universal monarch. Born in 1500 in the Flanders to Philip the Handsome...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Esk0!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa64775a4-bfc4-402f-990c-7967d954773d_1045x720.png)

Homie could have published this in a periodical lmao great work

This dude should just write a book 😂. Looks like a good read though.