Last Things was a guest speaker at the Old Glory Club’s “Taking the Reins” Conference, where he delivered the following presentation.

It has often been remarked that neo-reactionary theory is a postmodern movement. Many people who accept the label of “neo-reactionary” still balk at this categorization, which is understandable. “Postmodernism,” as a category of thought, is widely — and perhaps universally — considered to be a left-wing movement. The term signifies “the death of the meta-narrative,” the death of meaning, and the decline of many cultural values and norms that those of us here would seek to restore. It’s an undeniable fact that many of the primary thinkers associated with the term were card-carrying Marxists, and would have approved of the social and cultural changes that have occurred within the first quarter of the 21st century.

Grouping neo-reaction within postmodernism is typically a mere superficial, temporal categorization. After all, neo-reaction is a school of thought that has occurred and developed “after modernism.” And in this sense, there isn’t much to argue or object to. Thinkers like Mencius Moldbug, the founder of neo-reaction, traces his intellectual genealogy to people well outside the canon of postmodern thinkers, so perhaps this categorization would not hold up to scrutiny.

But I will argue that “postmodern” is not a label that we should shy away from; that much could be gained from familiarizing ourselves with, and indeed adopting and leveraging, many of the ideas put forward by the postmodernists. In fact, many of us have already begun to do so, whether deliberately or by accident.

The Death of the Author

If you have ever found yourself in a conversation where you are trying to elaborate on the features of an “accidentally based” film — a movie that, while ostensibly left-wing, and despite its intentions, delivers secretly based observations, presents likable based characters and dislikable progressive characters, or obliquely affirms based moral positions — your normie interlocutor will likely bring up “authorial intention” or its recent pseudonym, “media literacy.” A recent example of this which has happened to me, and I’m sure others in this room, is Dune: Part Two. Defenders of the film, as well as its director Denis Villeneuve, have stated that even if many of the narrative directions the film made did not line up with the book, it was nonetheless true to Frank Herbert’s original vision and position. Herbert wrote it as a warning about religious, messianic figures; we aren’t supposed to like Paul; etc. And, if you are like me, your response is: “Who gives a damn about Frank Herbert’s position?” Well, the idea we are relying on there is “The Death of The Author,” the idea that the interpretation or ultimate meaning of a work of art need not be confined to an author’s stated intentions, political opinions, or conscious reasoning.

This was a concept put forward by the French theorist Roland Barthes. In this scenario, it’s the normie who is assuming the reactionary position, and it is you who are approaching the context with a postmodern frame. The normie reactionary is relying on a claim to authority, and you are proclaiming the death of that authority. He invokes the “phallogocentrism” of Dune’s dead, white, heterosexual male author to deny your attempt to form your own meaning from a text.

While the biographies of many 20th-century postmodern philosophers might show us portraits of consummate leftists, it does not follow that ipso facto every thought categorized as “postmodern” is, by its very nature, a left-wing thought. We can leverage many of these ideas without endorsing the politics of many postmodern critics.

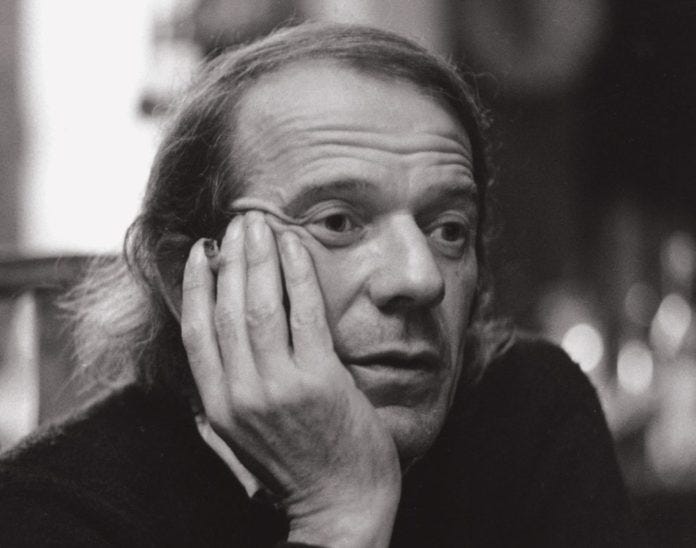

Gilles Deleuze

Thankfully, Gilles Deleuze presents us, in both his personality and in his body of work, with material that is readily amenable to neo-reactionary thought, and a biography that does not require much, if any, apologetics. Unlike many 20th-century French intellectuals, such as Foucault or Sartre, Deleuze was not a hedonist or a serial philanderer, or one who spent much of his time on political activism or defending the Communist Party. He was a married man and a father, and from what I’ve learned about his life and how he conducted himself, I find very little to object to. Contemporary social scientists, like Justin Murphy in his 2019 book Based Deleuze, seem to question whether or not Deleuze is even necessarily categorizable as “left-wing” in any sense that is traditionally associated with that term.

One quibble that I should state before diving into Deleuze: Technically speaking, Deleuze is a “poststructuralist” rather than a “postmodernist.” But still, he is more often than not lumped together with other philosophers from the 20th century who are grouped under the banner of “postmodern.” As for what “poststructuralism” is, that’s beyond the scope of this talk, and its definition is so broad as to be even more vague and slippery than the term postmodernism.

So, why examine Deleuze in particular? Again, when I first encountered Deleuze in college, I very quickly put him down, finding his prose intimidating, frustrating, quite possibly completely full of shit, and impenetrable. It was not until I revisited him two decades later, with the help of others and with secondary sources, that I could begin to see how valuable he was for understanding our circumstances.

First, I think that Deleuze offers us the best models for understanding our current moment. He provides concepts needed to perceive the mechanisms by which contemporary Western society seeks to control its subjects. Deleuze, despite having died in 1995, is the ultimate cartographer of the Internet and Internet culture. It would take a far more powerful autist than myself to distinguish what was prophetic in Deleuze from how much was directly influential. For example, we are all familiar with the term “Internet schizo.” Well, in his magnum opus Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Vol. I, Anti-Oedipus, Fr. 1972 [Eng. 1977]; Vol. II, A Thousand Plateaus, Fr. 1980 [Eng. 1987]), Deleuze claimed that human subjectivity would soon take on this “schizoid” quality within advanced, technological societies. We find much of his terminology, as well as his imagery, to permeate the Internet, from Nick Land’s Twitter handle to the flat planes of the vaporwave aesthetic:

Second, Deleuze is not only powerfully descriptive of our current moment; he offers us the best tools (what he refers to as “weapons”) to avoid getting stuck within the machines of captivity which I am about to detail. Unlike with his successor Nick Land, who is much more widely known and more readily associated as a scholar of the Web — but make no mistake; there can be no Nick Land without Deleuze — we find potential paths toward freedom and emancipation (what Deleuze termed “Lines of Flight”) that are far more affirming and white-pilling than the pessimism of Landian Accelerationism. By better understanding these weapons, we increase our chances at “taking the reins” (or, as Deleuze would put it, “avoiding captivity and enslavement”).

Before I can get to these weapons and how we might deploy them — or provide examples of how I think dissidents have already begun to deploy them — I need to provide a quick Deleuze 101 primer. We need to lay out a few of his key concepts, especially his concepts of “Societies of Control,” “Becoming Imperceptible,” and, most importantly, the “Nomad War Machine.”

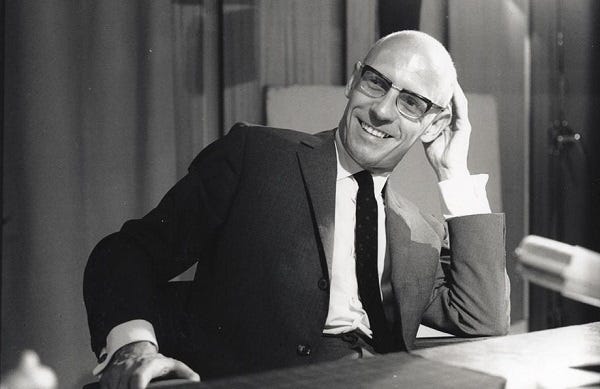

Michel Foucault

I need to start with another French philosopher for a moment here, Michel Foucault, as he provides us with an excellent point of entry for Deleuze.

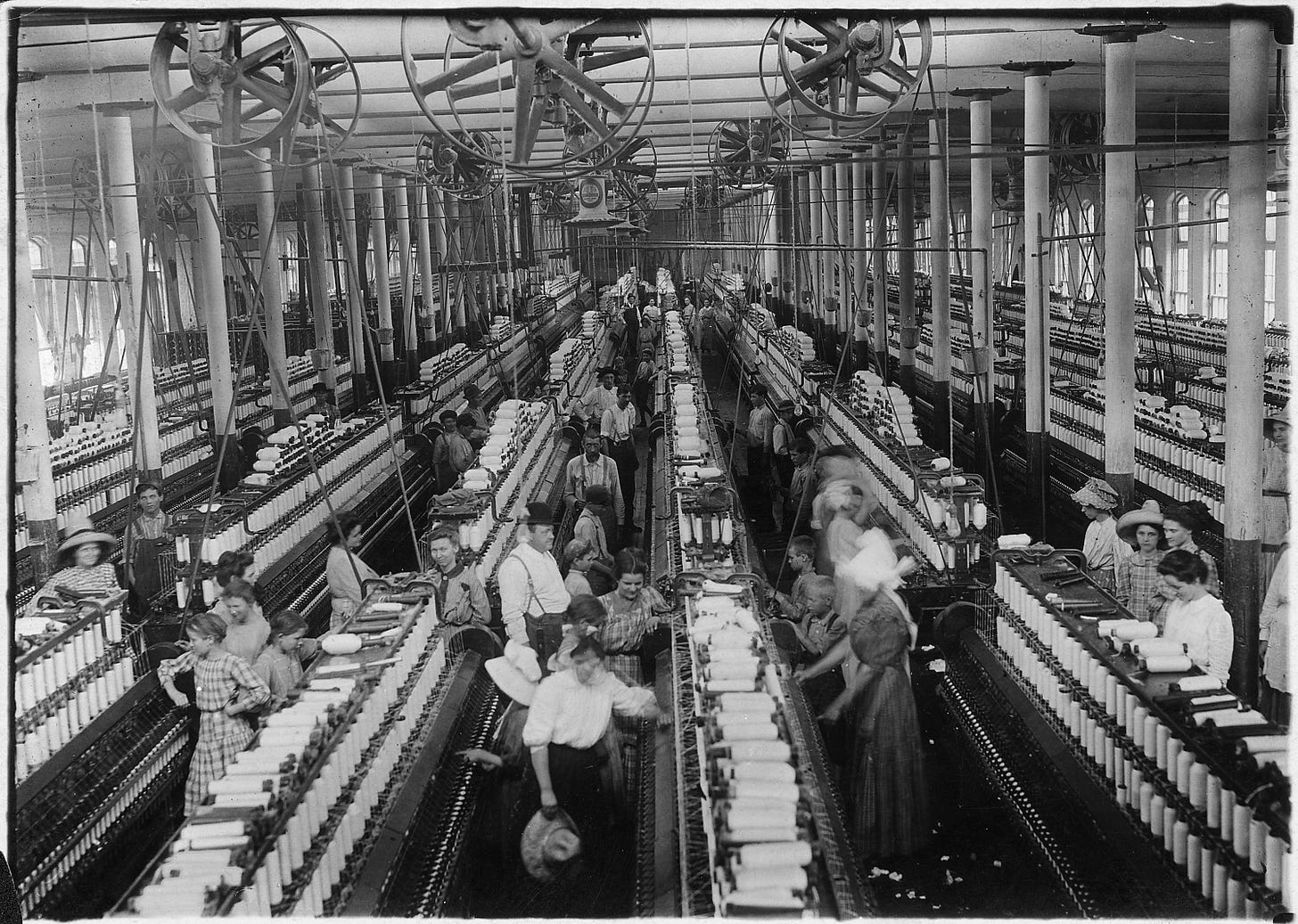

One of Foucault’s most famous concepts is that of the “Disciplinary Society.” He used this term to describe the cultures of the 18th and 19th centuries and the institutions they evolved to manipulate their subjects, institutions which Foucault described as “environments of enclosure.” Some examples include The School, The Barracks, The Factory, The Prison, and The Hospital. (Something else that Foucault considered one of these institutions, quite stupidly in my opinion, was “The Family,” which I have omitted. A mistake and miscategorization that the Left has gone on to make again and again now for decades.)

According to Foucault, subjects of the Disciplinary Society passed through these different environments as they passed through different stages in life. They were never at any point free of them, or standing outside these enclosed spaces; they were always subjected to one or the other, moving from The School, to The Factory, to The Hospital. The point of the Disciplinary Society and its institutions was to extract production from its subjects. (This differed dramatically from what Foucault claimed preceded it, namely the “Societies of Sovereignty” which sought to tax their subjects, as opposed to organize their production.) It’s easy to see how the Disciplinary Society aligns with industrialization, and Societies of Sovereignty with feudal, agrarian societies.

A quick side note here is that, while there is maybe a certain Marxist heritage to Foucault’s thinking here — we are examining labor, production, economics, and class and how these things inform human subjectivity — I don’t find anything that I, as a reactionary, ipso facto need to object to or reject within Foucault’s model in order to maintain my legitimacy as a reactionary, with the one exception of his having categorized The Family as an institution of enslavement.

Societies of Control

In his 1992 essay Postscript on the Societies of Control, Deleuze stated that, while he found Foucault’s articulation of the Disciplinary Society and its institutions to be an accurate model of industrial societies, this form of society, along with its institutions, was well on its way toward extinction, at least within the West. To quote Deleuze: “Whatever the length of their expiration periods, it’s only a matter of administering their last rites and keeping people employed until the installation of the new forces knocking at the door.”

The new model of society that was beginning to emerge is what Deleuze termed the “Society of Control.” Unlike the old institutions of the Disciplinary Society, which operated within a closed system, the methods of capture that the Control Society utilizes are less explicit, linear, and sequential; more free-floating and decentralized; in a state of constant evolution; and, most interestingly, self-administered.

The Factory has given way to The Corporation. The disciplined factory worker has given way to the self-actualized entrepreneur. The watchful scrutiny of the assembly line foreman has given way to the panopticon of social media, to the perfectly affirming and positive LinkedIn profile.

One can argue over which society imposed more suffering and degradation on its subjects, but that would be missing the point. What is important here is how “captivity” (an umbrella term I am using to refer to either “control” or “discipline”) is administered. One unique aspect of institutions of the Control Society is that its subjects are required to affirm their captivity. To perceive their captivity as freedom, their limit as possibility.

I have often contrasted my own experience, in subjection to a Control Society, to that of my grandfather, who spent his life working in a mill (and therefore within a Disciplinary Society). While his life was no doubt brutal and difficult, his employer was, at the very least, mercifully indifferent to his inner state. As long as he was providing his labor and contributing to production, he was permitted his resentment. I doubt, for example, that my grandfather ever had to fill out an HR questionnaire that began with “Tell us what you love about your job.” The Control Society takes a more holistic interest in its subjects. Very few of us work in factories now. Since the lockdowns, many of us even work remotely, alone in a home office. But just because we are no longer physically entering in and out of disciplinary institutions does not mean that we have escaped captivity.

I don’t mean to limit this comparison to the domain of employment and the transition from the assembly line to the office. Deleuze is articulating an evolution here that is much larger and totalizing than something that merely impacts the workplace. The advent of the Control Society is also an evolution of politics, of power writ large. Deleuze saw this evolution out of the Disciplinary Society and into the Control Society as being facilitated by technological innovation. Power is no longer shaped to administer an industrial society, but rather to administer a digital, or cybernetic, society. The Disciplinary Society and its linear, sequential, explicit institutions are no more. Deleuze describes these institutions as having given way to a “web” or “net” of control — and keep in mind that this essay came out in the early 1990s, before terms like “Web” or “Net” were ubiquitous, and well before the Internet became a part of everyday life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Old Glory Club to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.