I will immediately address a glaring issue. The subtitle says, “Civil Rights Act of ’63,” but such a thing was never passed. We have a ’64 Civil Rights Act. Yet, if one were to read through the Congressional Record, say for June 11, 1964, one will find a section titled “CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1963.” No, this was not a defeated predecessor or something brushed under the rug. Instead, the Civil Rights Act of 1963 was later passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

To address continuity, we will return to the 1960 Civil Rights Act eventually. What I am about to talk about came up during my research for the ’63/’64 Act, and it illustrates a narrative trick still used to push the country leftward in all offices of power to this day.

While the Act was still in consideration, under the ’63 name, the debate was surprisingly direct. To summarize what you can quickly read from the Congressional Record for yourself, Senator Long, speaking for the Southern Bloc against the Act, has spotted a potential avenue for abuse. The Act was seeking to outlaw any discrimination from federal assistance, and Senator Long wanted to clarify that this assistance did not apply to insurance and guaranty. Long explains himself:

Mr. President, this amendment is intended to make sure that the bill does not do what its sponsors say it does not do… In connection with title VI, the distinguished manager of the bill said that section 601, which provides that in federally assisted programs there shall be no discrimination, would not apply to a bank which might be a member of the national banking system and would not apply to a State bank insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. As I understand, they are all required to be so insured.

This is the problem: The question is whether it could be construed to mean that a State bank, which must be insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, would be considered as being under a federally assisted program. The sponsors of the bill say that is not intended. If it were construed to be under a federally assisted program, it could be said that a person would be discriminated against because someone would not want to sell him his home—his own private castle—because he did not feel like selling it to him, or because a group of neighbors wanted their homes to be sold to persons whom they thought would be suitable as neighbors.In other words, section 601 could be construed to be an open housing ordinance in every city in America on the ground that no building and loan association or any lending agency that has guarantees from a Federal program could make a loan where there was discrimination involved on the choice of a neighbor.

Senator Long goes on to explain that this application would be insane and very much contrary to the wishes of most every American. He also seems to understand how the Civil Rights Regime was being established, saying:

Suppose it is not done. We are very likely to have some more of these 5-to-4 decisions by the Supreme Court in which someone can bring out a decision and say, “Hurrah! No bank or lending agency can make a loan to any person who wants to sell his private home—his own castle—who discriminates in any way in the acquisition or disposition of his home.”

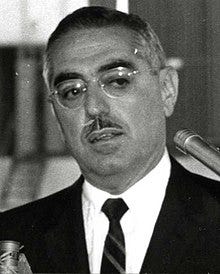

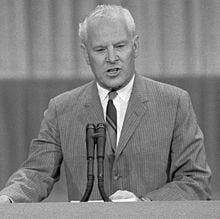

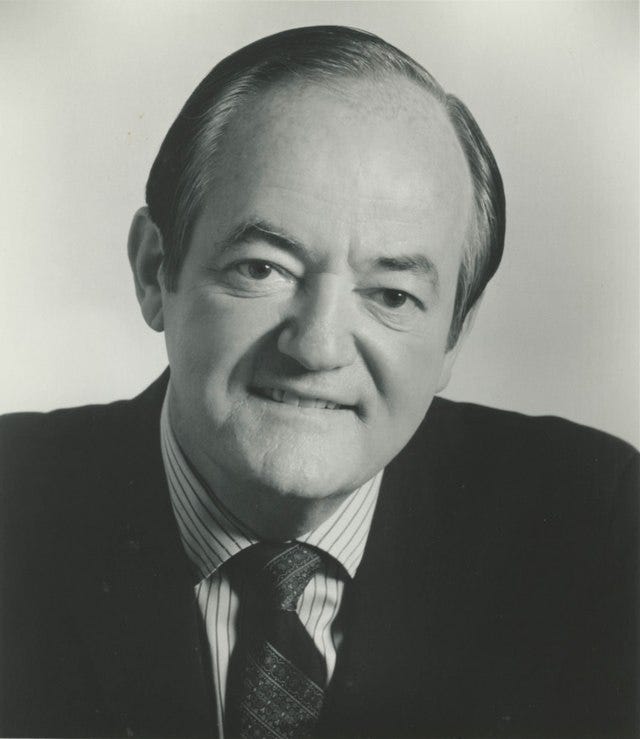

Senator Long was then accused of “beating a dead horse” by Senator Pastore, the Italian-American Senator from Rhode Island. Senator Pastore, and later, Senator Humphrey (the same one who ran in 1968 under the Democratic Party), both contended that civil rights legislation would never go so far as to have the federal government regulating the buying and selling of houses in the name of extinguishing discrimination.

Senator Albert Gore, Sr. then jumps into the mix to defend Senator Long. This attracts the attention of Hubert Humphrey, and the ensuing exchange is so valuable that I will just rip it from the archives beginning on page 13436. It reads as follows:

Mr. GORE: I yield for a question.

Mr. HUMPHREY: Mr. President, will the Senator repeat what he said? Hale any householder into court? For what?

Mr. GORE: For exercising discrimination in the selection of the person to whom he sells or rents his own home.

Mr. HUMPHREY: Even the wildest construction of that language could not possibly be interpreted to mean that.

Mr. LONG of Louisiana: Then, why not say it? Then, why not say it?

Mr. THURMOND: That is correct

Mr. GORE: I discussed this question with the Senator [Humphrey] yesterday. The Senator said the language did not mean that, and that he would accept an amendment.

Mr. HUMPHREY: No; I did not. I say most respectfully that the Senator [Gore] came to me and I said that, as far as I could see, I had no immediate objection.

This tactic used by Humphrey and Pastore is constantly used by regime apologists today. “We didn’t really mean what you think we meant, but we also won’t stop anyone from thinking we meant that either.” A more casual observer might say that “the mask is slipping,” that their true motivations have been revealed, and that they would affirm them entirely if they also didn’t need plausible deniability. Such a line of reasoning would surely make sense, especially considering how radically unpopular it would have been to force anti-discrimination laws onto housing.

Except they did exactly that, merely four years later. In the modern day, with our news cycles fluctuating at the speed of light, four years seems like forever. However, during the turmoil accompanying the founding of the Civil Rights Regime, four years is nothing. Four years is about how long each new Civil Rights Act was enacted, after all. Each four-year period brought with it a radically new overreach from the Federal Government, which was progressively involving itself in the lives of more and more Americans in the name of anti-discrimination.

So, far more than just a mask slipping, what we see are politicians using momentum, capitalizing on the turmoil and outrage resulting from their cultural revolution as justification to be more revolutionary. To put this into slightly different words, the slippery slope is being used as a deadly weapon, with each slide bringing us farther down the slope. The farther down the slope we go, the steeper the slope downward. The steeper the slope, the faster we fall. The revolutionaries recognize this, implicitly or explicitly in some cases, and they gleefully use it.

In the case of the ’63/’64 Civil Rights Act, this refusal to submit to a fairly basic request, specifically to add a small amendment to keep simple promises, furthered us along. If Humphrey and the other supporters wanted (or even needed) plausible deniability or good will or legitimacy, they would have agreed immediately and came back to this issue later. Instead, they decided to fight it.

They know everything naturally tends their direction under the current system, especially so under the Civil Rights Regime. If you are reading this, I’m sure you implicitly knew this too. Now that you explicitly know, one question remains. How is this knowledge to be used?

Here’s a good start: Do not grant the Civil Rights Regime any framing of its own. It is not good, and its fundamental assumptions are wrong. It is very clearly a tool for tyrants. Entertaining any of it is to push our country ever closer to the cliff edge out of a morbid curiosity to find out when and where we will plummet. And if revolutionaries are going to push their agenda using your outrage, the solution is not necessarily to inhumanly do away with emotion and reaction. Perhaps the solution is to remove the revolutionaries.