Ghosts of an Undiscovered Country

A review of “Thrilling Adventures Among the Early Settlers” by Warren Wildwood

Back in the old days of YouTube, just before COVID, when the sides of the Culture War still talked to each other and everyone was trying to figure out “those crazy SJWs,” I remember discovering the phenomenon of leftist Twitch political streams. I first encountered this genre late in 2019 when someone sent me the link to a transgender political streamer who dished out leftist political screeds in long form. In the video, the individual gave an hour-long diatribe against everything traditionally normative: any concept of hierarchy, religion, gender, or even the notion that people should be allowed to raise their children. However, as a pallet cleanser to the outrage, the streamer seamlessly transitioned into a celebratory soliloquy about his favorite video game, much to the delight of his live viewers. The broadcaster breathlessly informed his audience that this beloved video game series was such a masterpiece, such a pinnacle of human artistic accomplishment, that its legacy would be near-eternal. Without a hint of irony, the speaker then confidently predicted that in 300 years people would still be reveling in the sublimity and depth of the game, truly art for the ages!

At this point, I couldn’t help but laugh.

This leftist Twitch streamer condemned all past normative and aesthetic values as “fascist.” Not only would his life be anathema to any one of his ancestors; he had declared war against anyone seeking to carry forward the traditions which had created him. In the streamer’s worldview, the past was nothing more than a bleak morass of oppression, offering nothing in the way of wisdom but a shackle that prevented him from embracing his truth in the present. Yet his understanding of the future was not an infinite flowering of novel possibility, but the eternal return of his ego, to the extent he fancied that future ages would celebrate his self-sterilization as mankind’s greatest act of heroism, and his favorite toys as the highest form of art. It was the world of the eternal narcissist: the past could be nothing more than a primordial bleakness before the emergence of the self; the future would be nothing other than an Egyptian celebration of the ego, frozen in aspic.

Of course, even in 2019, I was aware of the common Internet narcissist disconnected from history and values outside the fulfillment of desire. The word bugman had been in broad circulation since 2016, and “Reddit-brain” was becoming more common as an insult. But what was less clear to me, until that moment, was how central this problem of atomization and disconnection was to our modern political crisis. It wasn’t simply a matter of being shallow or “small-souled.” It was a larger issue with how modernity understood the role of the individual and his relationship to the past.

As a child growing up in California, I was always taught the distinction between being “forward-looking” and “backward-looking.” We were instructed always to be looking towards the possibilities of the future; looking back was the purview of bitter clingers poorly adapted to the time. History was perfunctory, maybe superfluous. The real task was to understand change, reconcile yourself to where the world was going, and make those circumstances work for your life.

Altogether, I didn’t recognize until later in life how important an understanding of the past was to the task of building a future. The person who could not conceptualize a past of which he was a part could not properly form an understanding of a future worth living and dying for. He would remain the eternal child, as Cicero put it. Only those living as part of that great chain, only the men and women “living historically” as Thomas777 puts it, could persist in the history that would carry on after their brief lives passed from the scene.

But how exactly does one live historically?

It sounds easy enough in theory, but it is much harder in practice. Because, as much as we might want to tell ourselves otherwise, the bugman is not some creature from the darker sides of Twitch and Reddit, but an element of our own souls, a mode that we fall back into again and again once we become comfortable, a mode of life that all modern systems are designed to promote.

Living historically means living inside of a harsher reality, one that requires investment. And as we have all learned in the 21st century, reality is hard. That’s the issue with modernity: you want to connect with something more instantiated, deeper, and more collective, but you don’t even really know what that would mean.

Over the last year, I have noticed a subconscious theme in my writing, the theme of “peoplehood.” I originally addressed this topic in passing at the Witan conference in early August. Subsequently, this concept seemed inescapable, both online and in everyday life. The critical reason why mass immigration doesn’t work? The driving force behind various international conflicts? The reason we don’t know our neighbors in our diverse housing community? Even the difficulty my students experienced in understanding why God would call a given tribe “chosen”? Each problem was driven not so much by a presence as by an absence, an inability of modern people to understand collectivity as it was experienced in history, and an inability to live under a collective understanding of being both political and distinct at a given time and place.

Finally, towards the end of the year, a friend who had read some of my writing and noticed the theme asked the real question pointedly: “So, Dave, whom do you consider ‘your people’?”

I had to admit that I didn’t have a particularly good answer.

I had answers that I wanted to give. I wanted to say, “American,” “Californian,” or even “Broadly European.” But these weren’t responses that would mean anything, not in the deep historical sense. Being “Broadly European” or “White” is far too general to mean anything. And was I really “American” or “Californian”? To the extent that the latter meant anything at all, the Golden State’s identity was dying in my grandparents’ generation and dead by the time I graduated from high school. As for being American, my family were recent immigrants, with no roots in the New World beyond those put down in the supremely memoryless West Coast in the early 20th century.

Still, I remember the desire to cultivate such an American identity throughout my life. There was a magic to the country that even my European-born father saw in his love of American historical fiction and Californian history, a magic that I also sought as a young man in folk tales, Old-Time fiddle, and obscure history books. What came of this exploration is hard to say, but as a father now, the question of identity, especially in the America of the 21st century, returns with urgency. I want to have a home, a people, and a history. I want to give these things to my children. But it is hard to understand exactly how such things can be cultivated.

Perhaps it’s for this reason that I jumped at the opportunity to review Antelope Hill’s new edition of Thrilling Adventures Among the Early Settlers by Warren Wildwood, an anthology of folk tales of Early America (originally published 1861), describing many of the more obscure stories and tales of early America well beyond what my progressive schooling gave me or what my independent understanding of American folk culture revealed.

I have read many collections of American historical anecdotes and folktales, and Thrilling Adventures was certainly not what I expected. Less a collection of developed narrativized history (e.g., Barbara Tuchman), nor a collection of pioneer yarn or Western short stories, Thrilling Adventures instead functions as a collection of mini-histories and vignettes decidedly focused on American military history and conflicts between settlers and natives, jumping radically across geography and time to provide a blended, somewhat chaotic, and tragic picture of an Old America very distant from the place we now occupy.

Altogether, I enjoyed the book thoroughly. If this were a technical review rather than a reflection, I would give it a high mark. Nevertheless, I anticipate that Thrilling Adventures Among the Early Settlers will provide a great deal of difficulty for the general reader, even in dissident spheres, and I would be hesitant to recommend it to anyone who didn’t have a deep knowledge of late 18th and early 19th-century history.

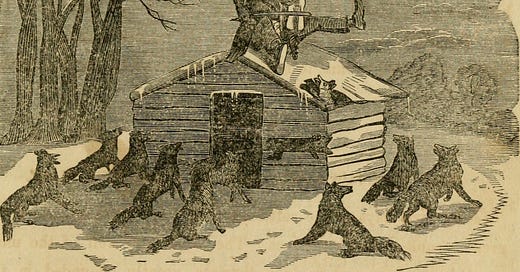

Yet the featured tales did speak to me, especially those that intersected somehow with the culture, geography, or history that characterized my own family’s time on the continent. Notable among the various chapters I appreciated: “The Jersey Refugee” and “How a Brave Man Saved Detroit” due to my familiarity with the described geography, “The Murderer’s Ordeal” which resembled the various popular murder ballads found in American Old-Time music, and probably not least “The Wolves and the Darkey Fiddler” because it featured the travails of a fiddler and reminded me of my favorite Grateful Dead song, “Dire Wolf.”

However, some readers will struggle to appreciate these stories. Each vignette is minimal, with a sparse background, and stated in a matter-of-fact, colloquial tone distinct to its time. As such, a reader may feel violently transported into any story with little in the way of the background necessary to appreciate the tension or the catharsis of the plot.

Still, I think broadly these stories succeed in their intended purpose. What we are receiving in Thrilling Adventures Among the Early Settlers is less a set of stories than a reel of snapshots, experiences torn out of their time and hoisted into ours like the Ghosts from a long-forgotten world. The encounter feels jarring and indecipherable, but that is probably part of the point.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Old Glory Club to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.