Knights of the Final Filibuster

The Knights of the Golden Circle: The Last of the Land Pirates

The 19th century was an age of clandestine secret societies and rogue paramilitaries roaming the New World. Among the vast pantheon of secret societies, the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC) is one of the most famous but least understood. The allure of the KGC mythology is the intersection of early American-Latin diplomacy, the collapse of the early American Republic into the Civil War, and conspiracy theories regarding the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and hidden caches of Confederate gold.

The goal of the organization was grandiose and tantalizing for alternate history buffs: the conquest of a vast swath of territory within the 2,400-mile circumference of Havana, Cuba, on behalf of Southern expansionist interests. The membership of the KGC consisted of an ideological coalition of large Southern plantation landowners known as Planters, pro-slavery orator Fire-Eaters, fire-and-brimstone Calvinist pastors, disgruntled veterans of the Mexican-American War, and plundering land pirate filibusters. Some KGC members embodied all five of the separate elements of the coalition, such as John Quitman. The method by which the KGC wished to expand into the Caribbean was through the aforementioned method of filibustering.

Filibuster was originally a 16th-century French term for Dutch sea-roving pirates. The term was later used as a synonym for buccaneers and Caribbean pirates. Spanish colonists then began ascribing the term filibuster to Anglo-American land pirates in the early 19th century. Between 1783 and 1865, the United States produced a plethora of volunteer militias which attempted to overthrow the legitimate governments of former Spanish colonies and seize the colonial land on behalf of American interests without the authorization from the American government. The early 19th century was the age of the filibuster. As I defined in my previous Old Glory Club article “A General History of American Land Piracy”:

In the early to mid-19th century, American adventurers had a get-rich-quick scheme for land piracy that could be distilled into a general formula:

Acquire political backing from politicians who see the addition of new land as a geopolitical boon.

Sell bonds and promise land to wealthy patrons in exchange for funding to acquire guns, ships, and mercenaries. Bonus points if American business interests have a foothold in the targeted territory before the invasion.

Invade a lightly defended Spanish colony with an irregular paramilitary force and topple the tin-pot colonial administration.

Declare independence.

Apply to America for annexation.

Get annexed by the United States before the Spanish can mount a decisive counteroffensive. If the U.S. refuses to annex the territory, politely ask to be made into a protectorate territory of the “informal empire” or “economic sphere of influence.”

Sell off the newly acquired territory for profit.

At the peak of their power in 1859, the KGC began mustering approximately 14,000 men in Texas in preparation for a paramilitary invasion of Mexico. This invasion never came to fruition due to the Election of 1860 and the Civil War, at which time the Knights pivoted to supporting the secession of the Confederate States of America. The KGC paramilitary militias became the backbone of the early Confederate militias while the KGC castles north of the Mason-Dixon Line became Copperhead Democrat networks for spies, saboteurs, and antiwar activists.

By 1863, the Knights of the Golden Circle permanently dissolved due to prosecution from the Union government in the North and the redundancy of its modus operandi in the South. However, survival theories abounded immediately after the Civil War, and the KGC’s legacy as a megalomaniacal secret society of American history’s most vilified political persuasions (belligerent jingoists, rogue militias, pro-slavery activists, and religious fundamentalists) still lives on in popular culture to this day.

The First Filibusters

From the birth of the American nation in 1776, the United States had aspirations of territorial conquest. While Federalists like Alexander Hamilton wished to finance an industrial mercantile empire of urban commerce, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, wished to expand their Empire of Liberty through territorial expansion. In 1786, Jefferson wrote:

Our continent must be viewed as the nest from which all America, North and South, is to be peopled.

Jefferson later wrote to Jacob Astor, America’s first millionaire, in 1812 that he

looked forward with gratification to the time when the entirety of the Pacific Coast would be populated with free and independent Americans. It is impossible not to look forward to distant times, when our rapid multiplication will expand itself and cover the whole northern, if not the southern continent.

The means by which Thomas Jefferson’s Republican coalition intended on carrying out the multiplication of his idealized population of yeoman citizenry (self-sufficient, land-owning homesteaders) was peaceful territorial acquisition via diplomacy and small, irregular hostile takeovers.

Caitlin Fitz writes in her book Our Sister Republics that, in 1800:

Many U.S. onlookers felt like passengers aboard Noah’s Ark, a lonely republic bobbing alone in a churning sea of monarchy and responsible for the fate of republicanism itself. “Now we stand in a trying, a peculiar, and an isolated situation,” one Philadelphia newspaper avowed. “We are the only free government upon the earth. America is left among the nations, a solitary republic.”

Some Federalists even lamented the republicanism unleashed upon the world following the catastrophic Haitian Revolution and French Revolution. In 1810, former President John Adams wrote:

Did not The American Revolution produce The French Revolution? And did not the French Revolution produce all the Calamities, and Desolations to the human race and the whole Globe ever Since? I meant well, however… I was borne by an irresistible Sense of Duty.

While the American public of the 1790s and early 1800s lamented the atrocious descent into violence as seen in the French Revolution and Haitian Revolution, glimmers of hope emerged out of Latin America. In 1808, the vast territories of Spanish-colonized America erupted with sporadic waves of independence movement insurrections, often proclaiming aspirations towards the founding of republic governments modeled after British parliamentarianism and American republicanism. Early America orators would frequently refer to the nations founded in the wake of these movements as America’s Sister Republics.

According to Our Sister Republics by Fitz, the early American perception of Latin America was that of enthusiastic optimism. Although the Kingdom of Spain aided the United States in their War of Independence with military and financial aid, the American public across the political spectrum rhetorically supported the Latin American Revolutions against Spanish and Portuguese colonial overlords from the end of the War of 1812 until 1826. In this period, around 200 Latin American revolutionary emissaries traveled to the U.S. in search of aid and asylum, universally embellishing the righteousness of their causes and the similarities between their own struggles and those of the American Revolution. Simón Bolivar’s gradual abolitionism and social reforms appealed to Philadelphian and Bostonian audiences while Latin American economic free trade policies and republican governance appealed to both Yankee mercantile interests and Southern Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican political aspirations. While Napoleon occupied the Spanish mainland, starting in 1808, the Spanish colonies were ripe for the taking.

Fitz notes that out of 904 recorded 4th of July toasts, over half included toasts to the independence movements of Latin American nations, predominantly Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, and Peru. Bolivar hats were commonly worn during 4th of July barbecues, and over 200 babies were named after Simón Bolivar.

Throughout the Latin American Wars of Independence, Fitz notes that the American public contributed in three ways to aid their Sister Republics: thousands of Americans volunteered to fight for Latin American independence (usually as privateers and occasionally as mercenaries and commissioned army officers), New England merchants supplied revolutionaries with more guns and ammunition than any other supplier (other than Great Britain), and the United States became the first country in the world to extend formal diplomatic recognition to Gran Columbia (1822) and Brazil (1824). As I wrote in “Land Piracy”:

One such American filibuster was William Stephens Smith, the brother-in-law of John Quincy Adams. Smith and 200 other filibusters joined the revolutionary army of Francisco de Miranda to liberate Venezuela in 1806. Smith’s ships were intercepted by the Spanish before they could invade. Smith was then sent back to America, where he was found not guilty of violating the Neutrality Act of 1794. Smith would later have a successful career as a Federalist congressman.

As generous as Americans were to South American independence movements, Americans rarely, if ever, toasted to Mexican or Haitian independence. South American independence was geographically far enough away from the United States for it to exist as a flattering abstraction. Northern Abolitionists and Southern Jeffersonians could indulge themselves with vindication of revolutions modeled after their own taking place in a far-off land. Information from South America was more frequent and more positive in affirming of their American audiences on the righteousness of the U.S. form of government. The United States also received more news from South America than from Mexico. In the port of Philadelphia in 1807, for instance, only seven ships were sent from the Mexican port of Veracruz, compared to 138 from Cuba, 18 from Puerto Rico, and 29 from La Guaira (Argentina). Less trade means less press coverage. At the same time, news coverage of Haiti and Mexico was often bleak. The brutal Haitian Revolution and the bloody Mexican War of Independence were seen as repugnant by most Americans, and unlike the South American independence wars, they provided fewer safe ways of profitably intervening unless the Americans acted like piratical opportunists extracting a pound of flesh off of Spain’s rotting colonial corpse.

As I discuss in “A General History of American Land Piracy,” the borders of the early American Republic were sparsely populated, scarcely defended or governed, and legally ambiguous, leading to several invasions, coups, and hostile takeovers. The first of these filibuster invasions was on September 23, 1810. In retaliation against the poor governance of the abusive Spanish alcaldes, 80 armed American settlers rushed the Spanish garrison of Baton Rouge, West Florida. These men then declared independence from Spain as the Republic of West Florida. This new nation was absorbed into the State of Louisiana two and a half months later.

This incursion was the first of many, with American western and southern frontier colonists raiding poorly defended Spanish garrisons in hopes of being able to hold on to them long enough for the United States to annex the territory. Several filibusters tried and failed to seize East Florida, such as George Matthews and Gregor MacGregor. Several filibusters also tried and failed to seize Spanish Texas.

Seeing fertile, unused, and unclaimed land, Louisianans jumped at the chance to cross the Sabine River and lay claim to Mexican land. This coincided with a hairbrained scheme by Vice President Aaron Burr to launch a frontier invasion of Mexico and declare independence from the United States in 1806. Burr was discovered and arrested, and these border settlers were then pushed out by a large Spanish military buildup of 1,368 men on the Mexican riverbank of the Sabine. Only four years later, Father Miguel Hidalgo launched the Mexican War of Independence.

In the chaos of the revolution, retired army captain Juan Bautista de las Casas attempted to launch a coup against the Spanish Texan governor. This coup was quickly put down, but survivor Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara was able to flee to the United States to request aid in his rebellion. Rather than overtly support a coup in a Spanish colonial province, the governor of Louisiana permitted Gutiérrez to recruit Americans to filibuster Texas. Alongside U.S. Army artillery officer Augustus Magee, Gutiérrez and 300 men marched into Spanish Texas, only to meet a Spanish army over twice their size and perish in 1813.

In 1819, another American, James Long, attempted to seize Spanish Texas and declare an independent Republic of Texas — he failed twice. The fatalities due to the Mexican War for Independence and Comanche Indian raids resulted in the province of Texas becoming depopulated and even more susceptible to American filibuster incursions.

Americans eagerly supported Latin American independence movements abroad while opportunistically and underhandedly attempting to seize their Spanish neighbor’s land. However, support for Latin American independence reached its limits in 1826, with the failures of the Latin American republican experiments and the birth of the Democratic Party.

In 1826, a congress was held in Panama known as the Amphitryonic Congress, organized by Simón Bolivar. Discussed at this Congress were proposals for mutual military assistance and the creation of a supranational congress representing every nation in the Western Hemisphere. Although the John Quincy Adams administration wished to send attendees, many denounced the congress as a “love fest” and as subterfuge for Latin American abolitionists to subvert the Peculiar Institution of the American South. Among the detractors of the congress was U.S. Senator from Virginia John Randolph, who denounced the idea of U.S. delegates taking

their seat in Congress at Panama, beside the native African, their American descendants, the mixed breeds, the Indians, and the half breeds, without any offense or scandal at so motley a mixture. These principles — that all men are born free and equal — I can never assent to, for all the best of all reasons, because it is not true. Inalienable rights, self-evident truths, equal creation? A most pernicious falsehood. No rational man ever did govern himself by abstractions and universals.

The early United States was a functioning tapestry of civic republican engagement. What had Latin America produced after decades of struggle for independence? An Age of Caudillos — juntas overseen by authoritarian aristocratic military strongmen. Multiracial Catholic republics that freed their slaves from their bondage did not prosper; rather, they sunk into dictatorship and oligarchy.

Even if the United States was no longer the only nominal republic in the Western Hemisphere, it was the only exceptional one. This sense of exceptionalism spurred a rise in nationalistic chauvinism among the new Southern Democrats who embraced Jacksonian democracy — expanded suffrage for all white men — and embraced the institution of slavery, not as an outmoded and antiquated technology but as a positive societal good, and pushed in favor of territorial expansionism to seed the entire continent with American planters. To the new Southern Democrats, their fallen Sister Republics were not allies; they were roadblocks.

Rather than tiptoe around the Jeffersonian contradiction of being a slaveowner egalitarian proclaiming that “all men are created equal,” the Southern Democrats amended their party rhetoric to match the reality that political equality is an obvious myth, slavery is a positive and profitable good, and Catholics and Africans cannot create republics. In their view, America is exceptional, and its republicanism is due to the content of its citizenry rather than the universal applicability of its structure; and its expansion is manifestly obvious in the competence of its governance and the incompetence of Latin America’s. As Simón Bolivar astutely prophesized, “The United States appear to be destined by Providence to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.”

The Filibuster Wars

In 1819, Scottish novelist Walter Scott published the historical fiction book Ivanhoe. This romantic epic depicted the titular Wilfred of Ivanhoe’s chivalric deeds and his struggles against the dastardly Knights Templar. Like many fantasy novels of the modern era, Ivanhoe grew a following of LARPing nerds who liked to pretend to be medieval knights. The chivalric pop culture craze of the 1820s became intermixed with the Southern U.S. fascination with civil society boys’ clubs, creating the modern chivalric secret society, not just for the elite, but for the masses.

The 19th century was the Golden Age of the Fraternity, with an estimated 40% of the adult male population being members of at least one secret society in the year 1897. From its inception, American republican civil society was a pluralistic tapestry of freely associating men. It was common for men of good standing to drill monthly with their state volunteer militias, participate in municipal committees of safety, education, and governance, and to belong to exclusive boys’ clubs for fun and mutual aid. For all their practical utility and encouragement of the common man to engage in political and economic communal decision-making, James Madison warned in the Federalist Papers:

A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation, as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions who have been interesting to the human passions, have, in turn, divided into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good.

In the mid-19th century, there was a plethora of secret society filibuster organizations, often using pre-existing secret societies like the Freemasons as networks to recruit mercenaries for invasions of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. From Andrew Jackson to Harry Truman, seven out of ten Democratic presidents were Freemasons.

In 1821, Freemason Stephen Austin began emigrating 300 American families into newly-independent Mexico’s province of Texas. At the time, Texas only had a population of roughly 3,500 residents, so the government of Mexico began encouraging Americans to colonize Texas and act as a buffer between the wild Comanche Indian raiders and the stable, populous, and profitable provinces south of the Rio Grande River. As part of the assimilation process, the Mexican government required that American immigrants to Texas convert to Catholicism, learn Spanish, and abandon the use of slave labor. One problem: Eastern Texas has the ideal geology for growing cotton, a profitable cash crop when slaves are used as a labor source. Tens of thousands of white Americans flooded into Texas, often illegally and bringing slaves with them. By 1834, the American population outnumbered the Tejano Mexican population four to one.

In 1835, General Antonio López de Santa Anna repealed the Mexican constitution of 1824 and plunged the country into a state of civil war. Americans in Texas then jumped at the chance to declare independence from Mexico. The early Texan revolutionaries were able to oust the Mexican garrisons at the Battle of Gonzales and the Siege of Béxar. However, by the spring of 1836, Santa Anna was able to consolidate his power in Central Mexico enough to be able to march north with an army to exterminate the Texan rebels. Santa Anna’s northern march was stalled at the forts of the Alamo Mission and the Goliad fort La Bahía. The sacrifice of the heroes at the Alamo and Goliad, including Freemasons David Crockett, James Bowie, William Travis, and James Fannin, allowed for their Masonic Brother Sam Houston, the first president of the Republic of Texas and general of the Texan armed forces, to recruit more men from the neighboring American states of Louisiana and Arkansas for the organized Texan army. Houston’s counteroffensive against Santa Anna ended decisively at the Battle of San Jacinto, in which Freemason Santa Anna was captured and forced to signed the treaty recognizing the independence of Texas under duress.

In the years immediately after the Texas Revolution, the Mexican government refused to accept the independence of Texas, often raiding Texan border towns between the Rio Grande and Nueces Rivers. To pay Mexico back for their harassment, the Texas government under President Mirabeau Lamar encouraged Texans to aid the Republic of the Rio Grande in revolting against the centralized Mexican government in 1840. The Republic of the Rio Grande was crushed in less than a year.

In its short life, the Republic of Texas maintained a small navy. Due to the exorbitant price of maintaining a navy and the immense amount of debt Texas was accruing, in 1843, Texan President Sam Houston formally disbanded the Texan Navy. Rather than disbanding his fleet, Texan Commodore Edwin Moore disobeyed Houston’s orders, retrofitted his fleet in New Orleans, and then sailed to aid the Republic of Yucatán in its war for independence against Mexico. In exchange for a monthly fee, Moore’s fleet patrolled the Yucatán Peninsula for Mexican navy vessels. on April 30, 1843, Moore’s fleet encountered a Mexican fleet off the coast of the Yucatán city of Campeche. Over the next month, the two fleets barraged each other in periodic naval engagements until the Mexican fleet lifted its blockade of the Yucatán city. The Republic of Yucatán used this tactical victory to bargain for increased autonomy from the Central Mexican government. Upon returning to Texas, Moore was welcomed back as a hero.

In spite of Texas’s occasional military victories, the Republic of Texas drowned in debt and was under constant threat of an invasion from Mexico to reclaim their lost territory. Although the American public was split along partisan lines on the annexation of Texas, Sam Houston began inviting ambassadors to begin talks of diplomatic recognition and Texan economic incentives for British investments in the country. This deft diplomacy forced the American State Department to annex Texas, for fear of having a potential British puppet state on its southern border.

To consolidate the Texan border at the Rio Grande River, Southern Democratic President James Polk instigated a war with Mexico in 1846. To provoke a war, Polk sent surveyor and spy John Fremont to stir a California rebellion against Mexico. Polk then sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico City to negotiate the American buyout of New Mexico and California from Mexico. The Mexican delegation refused and rebuffed Slidell, causing a diplomatic incident. Finally, Polk sent a contingent of two companies of dragoons into the disputed region of Texas between the Rio Grande and Nueces Rivers. When Mexican soldiers opened fire on the American patrol, Polk seized on the opportunity and invaded Mexico. The Mexican-American War was a decisive, one-sided war, ending in the American occupation of Mexico City.

During the American blockade of Mexico during the war, the autonomous Second Republic of Yucatán broke out into a bloody Caste War between the coastal elite mestizos and the poor, indigenous Maya. While the Maya rallied around the Cult of the Talking Cross to fuel their revolt, the Yucatán President Mendez send emissaries to Spain, Great Britain, and the United States, requesting military intervention in their race war in exchange for territorial annexation. On April 28, 1848, President Polk sent his Bill for the Relief of the Yucatán to Congress along with a letter for American lawmakers. In the letter President Polk wrote:

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States: I submit, for the considerations of Congress, several communications received at the Department of State from Mr. Justo Sierra, Commissioner of Yucatán, and also a communication from the Governor of that State, representing the condition of the extreme suffering to which their country has been reduced by an insurrection of the Indians within its limits, and asking the aid of the United States.

The communications present a case of human suffering and misery which cannot fail to excite the sympathies of all civilized nations. From these and other sources of information, it appears that the Indians of Yucatán are waging a war of extermination against the white race. In this cruel war they spare neither age nor sex, but put to death indiscriminately all who fall within their power. The inhabitants, panic-stricken, and destitute of arms, are flying before their savage pursuers towards the coast; and their expulsion from their country, or their extermination would seem to be inevitable, unless they can obtain assistance from abroad.

The Yucatán Bill was rejected. Only three months later, with the Mexican-American War over, the Mexican government intervened and quelled the Maya uprising in exchange for an end to the autonomy of the Republic of Yucatán.

Rather than settle for the acquisition of new territory from the Rio Grande River to California, filibusters began organizing militias to chip even more territory off of the ever-fragile Mexico.

On October 15, 1853, the 5′1″ “Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny” William Walker and 45 filibusters began marching to Baja, Mexico. The men easily captured the tiny town of La Paz and declared independence from Mexico. Word of Walker’s new Republic of Lower California quickly reached San Francisco, and the locals outfitted a ship full of reinforcements and provisions. After 250 more men arrived at La Paz, Walker and his filibuster army marched eastward to seize Sonora while leaving a small garrison behind in his capital. Walker would not reach Sonora. Instead, he was turned back after running out of supplies and being ambushed by Apache Indian raiders. Meanwhile, local Mexican landowners south of La Paz assembled a large militia, which forced Walker out of Baja California. Walker was president of the Republic of Lower California and Sonora for eight months.

Rather than settle for failure, Walker intervened in the Nicaraguan Civil War on behalf of the Nicaraguan Democratic Party in 1855. Walker and his 56 filibuster mercenaries (nicknamed the Immortals by the American press) were able to turn the tide of the war. Then, with the aid of 300 filibuster reinforcements, he was able to seize control of the entire country. As the new president of a united Nicaragua, Walker legalized slavery and made English the official language of the Nicaraguan government.

British industrialists, American tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Central American landowning conservatives feared the expansion of Walker’s filibuster nation, so they began to hire mercenaries and consolidate their forces on the Nicaraguan border. Walker’s fortunes turned in April 1856 when he launched a preemptive invasion of Costa Rica. Walker’s disastrous Filibuster War ended in Walker fleeing back to the United States and Walker’s filibuster cronies being ejected from power. A few months later, Walker attempted to stir up a revolution against the British-controlled Mosquito Coast (modern-day Honduras). Rather than extraditing Walker, the British authorities executed him for the crimes of “piracy and filibusterism.” William Walker died as one of the two great filibusters of the 1850s; the other was Narciso López, who attempted two filibuster invasions of Cuba in 1850 and 1851.

Throughout the early 1800s, Cuba faced the most violent slave revolts in its history. Many Cuban planters accused British abolitionists, such as David Turnbull, and British military intelligence of instigating the slave revolt and arming the slaves. In the mid-19th century, the Spanish government began toying with the notion of eventually abolishing slavery in the Spanish Empire at the behest of the British government. This shift resulted in some Cuban slave owners turning to agitating for Cuban independence or American annexation because of America’s extensive history of putting down slave revolts.

In 1849, Narciso López began to campaign for a filibustering expedition to free Cuba from the yoke of their oppressive Spanish overlords. López was promoted through partisan Democratic Party newspapers by John O’Sullivan and funded by several governors and prominent politicians, such as U.S. Senator from Missouri John Henderson and Mississippi Governor John Quitman — a war hero of the Mexican-American War and notable Freemason. López promised to sell these men public land owned by the Cuban government in exchange for cash. López also used American and Cuban Freemasonic lodges to network with potential benefactors. A long-term goal of many of López’s financial backers was to invest in Cuban sugar plantations. López originally invited several different veteran officers of the Mexican-American War to lead his invasion, including Robert E. Lee. However, every trustworthy officer López approached turned his offer down, forcing López to lead the expedition himself.

Both of López’s expeditions to liberate Cuba and preserve slavery ended in abject failure. López’s September 1850 filibuster saw 600 men raid a small Cuban city, starve in the Cuban jungle without the aid or goodwill of the locals, and flee back to America. In August 1851, López launched his second filibuster with fewer men, fewer supplies, and more immediate resistance from the locals. López’s smaller filibuster army of 425 men was ambushed by a Cuban militia, also starved in the Cuban jungles, and was eventually surrounded, captured, and executed.

In spite of the numerous filibuster failures, the backers of the Walker and López expeditions were not discouraged. Instead, they pooled their resources, money, and manpower into a single network whose goal was the annexation of Cuba and Mexico. This organization was known as the Order of the Lone Star (OLS). The Order of the Lone Star predated the López and Walker expeditions, but their membership exponentially expanded after the Filibuster War.

The OLS was a hierarchical secret society based on three degrees of membership: an entry-level military degree, a fundraising/networking degree, and a political influence degree. First-degree members would meet monthly and conduct firing and marching drills. They were also expected to enlist in potential filibustering expeditions when the time was right. Second-degree members were usually wealthy businessmen and well-connected state politicians who were not expected to travel in filibuster expeditions but who were still expecting to profit from them. Third-degree membership was reserved for governors, congressmen, and the upper echelons of Southern society and headed the OLS organization.

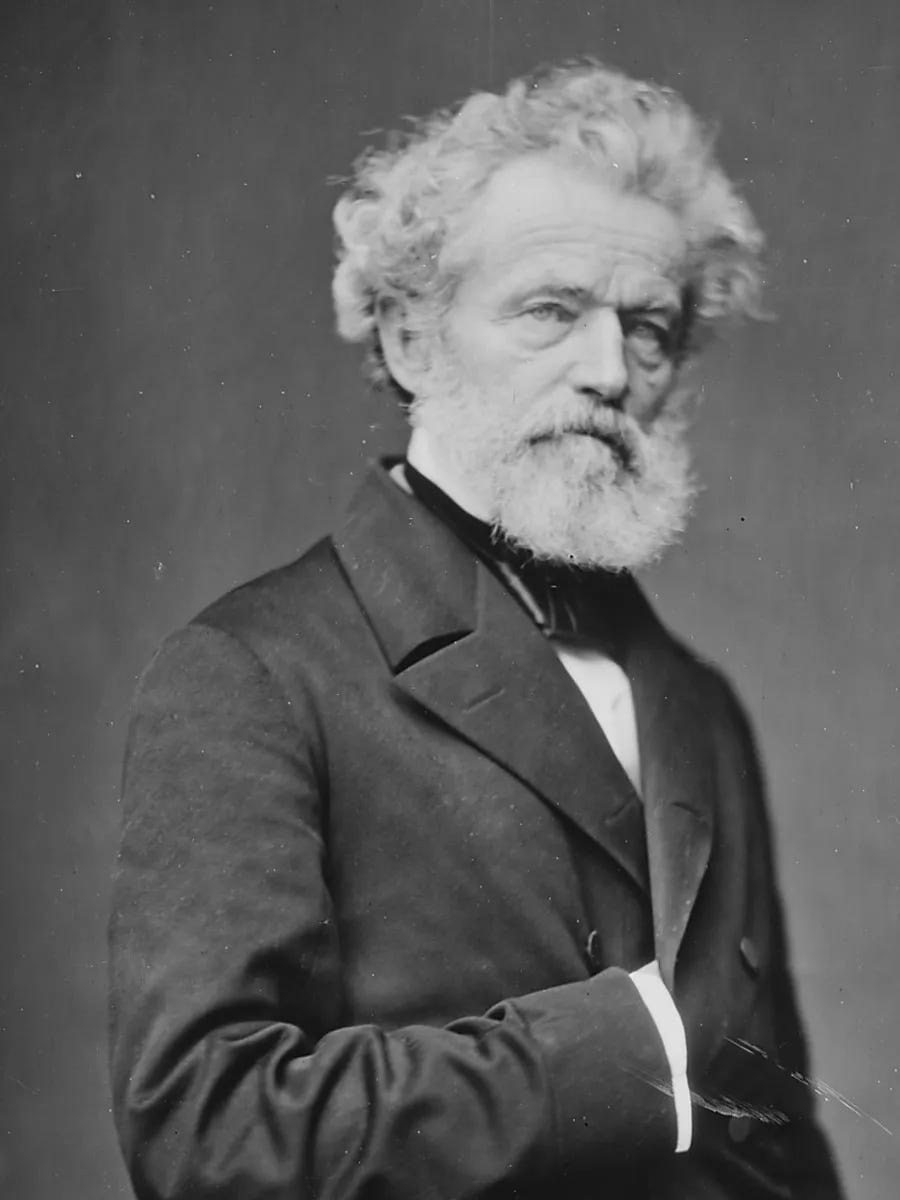

Senator John Henderson of Missouri developed special rituals, handshakes, and passwords for each degree, based on the template of Craft Freemasonry, while Senator Pierre Soule of Louisiana acted as the OLS’s first president and used his political contacts to form a political inner circle. By 1853, Mississippi Governor John A. Quitman became the formal leader of the OLS, imbuing the filibustering secret society with the additional political aim of expanding the institution of slavery to new territories. In addition to subsidizing filibuster expeditions, Quitman financed Southern Rights Associations across Mississippi and ran for vice president for the Southern Rights Party. Quitman was also a founding member of the Aztec Club of 1847, a 33rd-degree Scottish Rite Freemason, and the protégé of John C. Calhoun.

The annexation of 525,000 square miles from Mexico after the Mexican-American War resulted in a tidal wave of American settlers flooding into the new territories. The conversion of these new territories into states was an issue of contention. The addition of new states meant shifts in the number of congressional seats, adjusting the sectional partisan balance of power between Northern and Southern interests. Southern Rights Associations supported filibustering organizations, such as OLS, under the assumption that the newly-annexed territories would adopt the institution of slavery and elect pro-slavery congressmen. The North’s population and congressional representation was expanding faster than the South’s. So, Southern Rights Associations opted into opportunistically supporting filibustering operations so as to augment the representation of the South in the federal government. Jingoistic expansionism was generally opposed by the Federalists, Whig Party, and Republican Party. Filibustering was seen by these three political parties as practically ineffective and diplomatically disruptive. In the case of most filibuster expeditions, they were kind of right.

In the wake of López’s disastrous second invasion of Cuba, Quitman was convinced that the scale of the next filibuster army needed to be drastically scaled up. Instead of López’s puny force of 425 men (mostly Hungarian mercenaries) and a single steam ship, Quitman wanted to send a filibuster armada to Cuba. In two years, Quitman was given $1 million in advance from Cuban planters and expats, able to raise about $200,000 in funding, and aimed to recruit 3,000 men. Quitman wrote a letter to wealthy Georgia planter and illegal slave smuggler C.A.L. Lamar:

Our great enterprise has been planned with the advice and approval of some of the most distinguished men of the country. It contemplates aiding a revolution movement in Cuba with from three to four thousand well-armed and provided men in swift and safe steamers.

His letter was leaked to the press, who took it upon themselves to embellish Quitman’s logistics. The press claimed that Quitman had accrued $1 million in fundraising, acquired twelve ships and 85,000 small arms, and recruited 50,000 men. The Cuban governor quickly got word of the planned invasion and began arming slave and peasant militias. The diplomatic incident caused by the OLS resulted in Democratic Party insiders distancing themselves from Quitman’s organization. By 1855, with a complete lack of approval from the Democratic Pierce administration and with crippled recruiting prospects, Quitman was urged by famed Texas Ranger John S. Ford and John T. Pickett of Kentucky to change his filibustering target from Cuba to Mexico and to pool the OLS’s resource’s with an upstart filibustering secret society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle.

The Rise of the Final Filibusters

George W.L. Bickley was born in 1823 in rural western Russell County, Virginia, to a poor family. George’s laborer father died of cholera when George was five years old, leaving George’s mother in a destitute, emotionally distraught, and neglectful state. At the age of twelve, George ran away from home and began working odd jobs at supply companies. By 1850, George Bickley had been married, briefly attended a community college somewhere in Indiana, had a child, lost his first wife, and settled back down in Russell County, where he established a county doctor practice in phrenology. The next year, Bickley convincingly fabricated New England and European medical school credentials and began teaching at Cincinnati’s Eclectic Medical Institute. At Eclectic, 19th-century pseudoscience and quack alternative medicines thrived. While teaching at Eclectic, Bickley wrote History of the Settlement and Indian Wars of Tazewell County, Virginia, as well as Adalaska; Or, The Strange and Mysterious Family of the Cave of Genreva and Principles of Scientific Botany. Adalaska was an anti-slavery novel in the same vein as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Bickley might have been a con man unable to deliver extemporaneous medical lectures, but he had a tireless work ethic, producing absurd quantities of literature in remarkably short periods of time.

In the spring of 1853, Bickley married Rachel Dodson, the wealthy heiress of a banking family fortune. Bickley then quit his job at Eclectic and began converting his wife’s assets into cash, which would then be used to fund Bickley’s zany media startups. One of Bickley’s first media productions was a short-lived journal called Bickley’s West American Review, a compilation of flowery articles on Manifest Destiny (mostly written by Bickley himself).

Bickley began dabbling in political secret societies around the same time he tried entering the realm of political polemic media. Bickley formed a chapter of the Brotherhood of the Union, a vaguely patriotic and pro-expansionist secret society that provided mutual aid benefits for their working-class members. Bickley joined a lodge of the nativist Know-Nothing Party and began participating in a drill company (volunteer militias that regularly marched in uniform and competed with other drill companies for prestige). It is unclear when the Knights of the Golden Circle began, but the first three castles were started around Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1857, Bickley’s wife caught him trying to sell her family farm for cash to fund another failed political newspaper, leading to Bickley being cut off from his wife’s financing.

Throughout 1858, Bickley refined the imagery and structure of the Knights of the Golden Circle while working for the Scientific Artisan patent journal. An Artisan coworker described Bickley as “an ignorant pretender, as restless and scheming as he was shallow, very vain in his person, exceedingly fond of military display, and constantly engaged either in devices to borrow money and crazy schemes of speculation.” Rather than annoy his coworkers further, Bickley quit Artisan and founded the American Colonization and Steamship Company of Monterrey, a shell company for investments into Knights of the Golden Circle activities. Bickley then traveled across the South, working closely with pro-slavery Southern Rights Associations and selling KGC steamship bonds to fund potential filibustering expeditions.

Around this time, the Order of the Lone Star was becoming both large and aimless. Their planned invasion of Cuba never occurred, and their leader, Quitman, began professionally distancing himself from his own organization. The OLS was massive by 1858, boasting an impressive membership list of Democratic Party politicians and wealthy planters, approximately 15,000 members in total, and at least fifty chapters, mostly concentrated in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi. OLS also had chapters as far north as New York City, with one chapter operating out of Tammany Hall.

The Knights of the Golden Circle were structurally very similar to the Order of the Lone Star, but perhaps more theatrical in their Ivanhoe-LARP ritual costumes. During meetings, Knights would don knightly cuirasses and helmets with crescents on the helm. The symbolism of KGC insignias incorporates various elements of Masonic Commandery of Knights Templar garb. Knights also met regularly in “castles,” which ranged in style and size from simple barns, such as a KGC castle located in Reading, Pennsylvania, to Planter estate houses.

The KGC consisted of three degrees of membership, each with its own respective rituals, handshakes, passwords, and responsibilities. The entry-level first degree was known as the Knights of the Iron Hand. These Knights met monthly at castles (the KGC term for a lodge or chapterhouse) where they would initiate new members, conduct marching drills, and coordinate filibuster activities under the leadership of a castle captain. These Knights were expected to participate in filibustering expeditions as soldiers. The second degree was known as the Knights of the True Faith. These Knights often came from wealthier and more well-connected backgrounds and had the responsibility to raise money and material for filibuster expeditions. The third and highest degree was the Knights of the Columbian Star, or the American Legion. Third-degree members were expected to organize and coordinate their states’ castles and eventually to move to conquered territories to rule on behalf of the KGC’s “Army Council.” The membership and political aims of third-degree Knights were not disclosed to lower-degree members. To quote the ritual of the third degree:

We aim at the establishment of a great Democratic monarchy — a Republican Empire, which shall vie in grandeur with the old Roman Empire, and which shall regenerate and vivify society in Spanish America… We aim at the establishment of a government the fathers and founders of which shall be the Knights of the Columbian Star. To each of you we plainly say, the high places are for you; you have done more, and are expected to do more for the American Legion than the First-Degree Knights, and you deserve more.

Throughout 1858, Bickley began the process of converting western OLS chapters into more secretive KGC castles, adopting the new KGC paraphernalia, organization, rituals, and codes. By the spring of 1859, Bickley had shifted his efforts to forming a power base around Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, in the east. Among the new Maryland recruits was actor and future assassin John Wilkes Booth. During this time, Bickley pivoted OLS’s target and invasion strategy. The Knights of the Golden Circle would not illegally invade Mexico; they would be invited in.

In the first half of the 19th century, Mexico suffered from twelve coup attempts, three civil wars, and countless insurgencies and independence movements. The political instability can partly be blamed on the inability of the Federalist Liberals and Centralist Conservative factions to derive a united sociopolitical consensus after Mexico gained its independence:

Elite factions split into Liberals and Conservatives, whose eventual goals overlapped despite differences that contributed to ongoing civil wars. Conservatives hoped to maintain much of the colonial social order, including legal status for Indian communities and a role for the church in governance. Liberals sought to overturn the colonial caste system and its legal intermediaries in order to exert direct state control over the population. Liberals were also committed to the idea of progress based on foreign investment and the development of an export economy. Liberals and Conservatives shared deeply elitist and racist views, shaped by colonialism, that placed Euro-descendants at the top of the social hierarchy and saw Indians, in particular, and the rural poor majority, in general, as an obstacle to progress, fit only for service to their social and racial betters.

When the Liberals triumphed toward the end of the century, two of the main victims were Indian communities and the church. While Indians had been marginalized and treated as inferior under the colonial system, the Spanish had also recognized a fair degree of autonomy and especially communal land rights. The church, too, held large tracts of land. Liberals wanted a strong state that would eliminate or control these alternate sources of power. Abolishing collective land holdings and putting land for sale on the free market, they believed, would be the key to stimulating export production and economic progress.

American filibusters, such as William Walker, Joseph Moorehead, and Henry Crabb, appealed to Liberal factions for invitations to provide mercenary aid in their respective political conflicts in exchange for economic concessions (usually land grants).

In 1857, the Mexican Liberal President Benito Juarez reformed the Mexican Constitution. Mexico “prohibited slavery and abridgments of freedom of speech or press; it abolished special courts and prohibited civil and ecclesiastical corporations from owning property, except buildings in use; it eliminated monopolies; it prescribed that Mexico was to be a representative, democratic, republican country; and it defined the states and their responsibilities.” These reforms alienated both the Liberals’ indigenous constituents, whose communal land was privatized, and the Conservative clergy and military, whose special economic and judicial privileges were revoked. Tensions erupted into an all-out civil war when Conservative General Felix Zuloaga marched his army on Mexico City and attempted to seize control of the wealthy Central Mexican states, plunging the country into a disastrous Reform War.

Rather than invade Mexico outright, the Knights of the Golden Circle negotiated with President Benito Juarez to invite the Knights to intervene militarily in the Reform War on behalf of the Liberals, in exchange for large tracts of land in Northern Mexico. In the Knights of the Iron Hand initiation ritual, every new KGC enlisted man was promised 640 acres of Mexican land (3,200 acres of land for each Knight of the Columbian Star) in exchange for his service in reinstating a Liberal Mexican government. Once the Knights firmly embedded themselves in their newly settled territories, they then planned either to secede from Mexico, similar to the Texas Revolution, or to overthrow the Mexican government in a coup.

Bickley held a conference to discuss an intervention in Mexico in early August 1859 at the Greenbriar Resort in White Sulphur Springs, Virginia, attended by between 80 and 100 of his Knights of the Columbian Star. In attendance at the resort were Texas Ranger Ben McCulloch, U.S. Secretary of War John Floyd, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson, former Governor of South Carolina John Manning, former U.S. Senator from Louisiana Charles Conrad, and notorious Fire-Eater Edmund Ruffin. The Greenbriar was packed with approximately 1,000 guests, and the KGC conference attendee list has never been disclosed. Some of the aforementioned statesmen could have been at the Greenbriar for other business, but all of these guests either were known KGC members or were known to have had close ties to the KGC.

By early 1860, American popular opinion of the Mexican Reform War was that of pity. In his 1860 State of the Union Address, Democratic President James Buchanan dedicated a fifth of his address to the War:

We have been nominally at peace with that Republic, but “so far as the interests of our commerce, or of our citizens who have visited the country as merchants, shipmasters, or in other capacities, are concerned, we might as well have been at war.” Life has been insecure, property unprotected, and trade impossible except at a risk of loss which prudent men can not be expected to incur. Important contracts, involving large expenditures, entered into by the central Government, have been set at defiance by the local governments. Peaceful American residents, occupying their rightful possessions, have been suddenly expelled the country, in defiance of treaties and by the mere force of arbitrary power. Vessels of the United States have been seized without law, and a consular officer who protested against such seizure has been fined and imprisoned for disrespect to the authorities. Military contributions have been levied in violation of every principle of right, and the American who resisted the lawless demand has had his property forcibly taken away and has been himself banished. From a conflict of authority in different parts of the country tariff duties which have been paid in one place have been exacted over again in another place. Large numbers of our citizens have been arrested and imprisoned without any form of examination or any opportunity for a hearing, and even when released have only obtained their liberty after much suffering and injury, and without any hope of redress.

The KGC liked Buchanan’s analysis of the Mexican conflict so much that they incorporated portions of the speech into their first-degree KGC initiation ritual. Popular opinion and the sentiment of the Buchanan administration were on the side of the filibusters.

On January 26, 1860, Bickley sent out a circular letter to the Knights of Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama declaring that the invasion of Mexico was imminent and stated their long-term goal of establishing a protectorate over all of Mexico. This letter also appointed Elkanah Bracken Greer as the Grand Commander of the two Texas KGC regiments, “Commander and Chief” of the Mexico invasion, and KGC President of the Texas Board of War. Greer had raised $500,000 in cash and organized two regiments with a total of about 3,500 Knights in his state of Texas.

Although Sam Houston, former President of the Republic of Texas and then Governor of the U.S. State of Texas, may have been a member of the Order of the Lone Star himself, he opposed the filibuster invasion of Mexico and refused to endorse KGC’s plans. In a letter from Albert Lee to Houston, Lee expressed the sentiment of Colonel Robert E. Lee upon being approached to lead the KGC invasion force, reporting that “Lee would not touch any thing that he would consider vulgar filibustering; but he is not without ambition, and under the sanction of government, he might be more than willing to aid you to pacificate Mexico.” To circumvent the wishes of old man Houston, the KGC opted to infiltrate and subvert Houston’s Texas Ranger Division.

Upon receiving news of the KGC’s mobilization, other KGC castles outside of Texas began drilling more frequently, in anticipation of news that they would be ordered to ship off to join their fellow Knights in invading Mexico. Hundreds of Knights, from as far as New York, preemptively moved to Texas to join Greer’s regiments.

As Greer eagerly awaited Bickley’s order to invade, Joseph Davis Howell, the brother-in-law of future Confederate President Jefferson Davis, published a public letter in the New Orleans True Delta newspaper accusing Bickley of being a charlatan and a fraud. With Howell’s pronouncement, an avalanche of allegations came forward against Bickley, accusing him of financial irregularities, often insinuating that Bickley personally embezzled KGC funds. It is not known whether Bickley embezzled KGC funds, but what was apparent was the fact that Bickley’s Knights of the True Star were not able to raise the $2 million necessary to fund Greer’s invasion and Bickley had not secured the blessing of the Juarez government to intervene in the Reform War.

In response to his critics, Bickley sent out a circular letter, giving as honest an inventory of KGC’s strength and financial status as Bickley could muster. As David Keehn wrote in his book Knights of the Golden Circle:

Bickley’s circular letter presents a unique breakdown of the strength of the Knights’ army as of April 1860, as well as its state regimental commanders. Bickley first notes: “There is a Division of about 3,500 men in Texas and Arkansas under the charge of General Greer.” This estimate was probably in the ballpark since in January 1860, Greer said he had two regiments of Texas Knights “ready to move immediately,” and close to a thousand Knights were subsequently reported in Arkansas. Bickley next states: “There is a Regiment of about 1,200 men in Maryland in charge of Col. R.C. Tyler… a Regiment of about 1,000 men in Virginia in care of V.D. Groner; a Regiment in North Carolina of about 600 men in care of Maj. R.C. Tillery.”

Discounting the more speculative portion of Bickley’s enumeration, the actual regiments in Texas/Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, Virginia, and Tennessee would together indicate a KGC army of 8,300 men. In general, the KGC military strength was concentrated in two power centers — the 3,500-man division in Texas/Arkansas under Greer, and the almost 3,000 Knights in Maryland/Virginia/North Carolina under Tyler/Gronter/Tillery.

Bickley then announced that the KGC leadership would host a conference from May 7 to 10 in Raleigh, North Carolina, at which Bickley could privately respond to his critic’s accusations. The meeting was chaired by Robert C. Tyler, former filibuster under William Walker and commander of Maryland’s 1,200-man KGC regiment. Although the attendees of the conference were able to clear Bickley of any financial wrongdoing, they did strip Bickley of his oversight powers over KGC state commanders. Regional commanders like Greer and state regimental commanders like Tyler were given autonomy to raise money, enact bylaws, and appoint their own subordinates without the approval of the American Legion. Bickley would remain the President of the Order of the Columbian Star, but his Legion would, from then on, coordinate and support state regiments rather than lead them.

From May 16 to 18, the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago, Illinois. This Convention ended with the nomination of Abraham Lincoln as the Republican presidential nominee for the 1860 Election. The rise of the GOP fanned the flames of Southern paranoia regarding sectional Northern aspirations to abolish the institution of slavery.

In the Election of 1860, pro-Republican paramilitary known as the “Wide Awakes” allegedly committed acts of voter intimidation, vandalism, and arson against their Democratic foes. In response to the popularity of the Wide Awakes, Democratic presidential candidates formed their own campaign fraternities. John Bell of the Constitution Party organized the “Everett Guard” and “Bell Ringers.” Stephen Douglas formed election clubs known by several names — “Little Dougs,” “Little Giants,” “Douglas Invincibles,” and “Chloroformers” (in reference to Douglas’s presidential aspirations putting the Wide Awakes to sleep). The KGC’s involvement in downplaying the Wide Awakes was the dissemination of schizopost fear-mongering propaganda about the Wide Awakes trying to filibuster Nicaragua to set up “free soil homesteading colonies” before the KGC could.

On July 3, 1860, several newspapers in New Orleans reported that, according to the Mexican Liberal Party diplomat, “it is true that [the] organization of the Knights of the Golden Circle, and other societies in the United States, have offered to the constitutional government their assistance in the civil war now raging in Mexico, but the President has constantly refused every aid of this nature.” Beginning in August 1860, the Juarez faction also began winning battles against the Conservative faction and started pushing from the Liberal stronghold of Veracruz to the Conservative-held Mexico City. The Knights were no longer welcome in Mexico — they never were.

On July 8, a fire caused by an exploding keg of gunpowder destroyed a large portion of the Dallas, Texas, town center. Hours later, another fire ignited in the nearby town of Denton, allegedly caused by another gunpowder explosion. In the following weeks, copycat fires were reported across Texas. Paranoid Texans quickly descended into a conspiratorial panic, with many slaves being accused of conspiracy to commit arson, murder, and poisonings at the behest of Northern abolitionists. In response, local KGC castles changed their activities from drilling for an invasion of Mexico to forming committees of safety. The Texas KGC was converted from a filibustering organization to a secret police force and surveillance system bent on persecuting Northern travelers and putting down hypothetical slave revolts.

On October 17, 1860, Bickley delivered a lecture in Austin, Texas, to promote the KGC. Bickley presented the KGC as an organization that would accept the Election of 1860 provided that any candidate other than Abraham Lincoln won, stating that if Lincoln won, “resistance would surely follow, and the KGC would become the rallying army for the Southern disunionist.” During the Q&A portion of Bickley’s speech, retired judge George Washington Paschal asked Bickley, “I have understood that it has been said the order acts as spies upon travelers, and even marks baggage, and that baggage has come marked to this city as suspicious. Is it so?” Bickley glibly responded by saying, “It is. Baggage searching, the spotting of men ought to have been such an order thirty years ago. It was intended for the nutmeg men, the Yankee peddlers and other suspicious characters. Does anyone object to these sentiments and practices?” Paschal then went on a tirade, accusing Bickley of being a tyrant in the mold of Robespierre, aiming to overthrow the U.S. government.

Shortly before the Election of 1860 kicked off, a federal informant infiltrated a KGC “Council of War” in Texas and reported his intelligence to U.S. Army Colonel Joseph Mansfield. According to the informant, the Buchanan administration was infested with KGC members, including Secretary of War John Floyd, Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb, and Vice President and Democratic Party presidential nominee John Breckinridge. According to the informant, in the case that Abraham Lincoln was elected president, the KGC planned to seize navy yards and forts, seize Washington, D.C., and inaugurate Breckinridge as president. Mansfield believed that his informant’s intelligence was credible, so he sent word to incoming Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase. The newly-elected Republican President Lincoln was now aware of the looming threat of a KGC coup against his administration. The effort of the Knights of the Golden Circle to aid the secessionist movement and later to forge the Confederate States of America would be the KGC’s greatest accomplishment and the source of their eventual downfall.

The Fall of the Final Filibusters

The election of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican President, sent shockwaves throughout America. In spite of the fact that not a single voter south of the Mason-Dixon Line cast a vote for Lincoln, as the Republican Party did not run any candidates in the South, Lincoln nonetheless won the election on the sheer numerical advantage of sectional Northern electoral votes alone. Although Lincoln himself pledged not to interfere with the Southern institution of slavery in the states where it was already practiced, the principle that the Northern Republican Party could outvote the South was unacceptable, leading to the Secession Crisis.

Just as Bickley promised in his October 1860 speech, the Knights of the Golden Circle set out to coax Southern states to secede from the Union, attempted to launch a coup in Washington, D.C., attempted to assassinate Lincoln before his inauguration, and then became the vanguard of the early organization of the Confederate Army, before being sidelined in favor of West Point-educated officers with real military experience.

On October 7, 1860, South Carolinians drafted the constitution for the Minute Men for Defense of Southern Rights. Minute Men was a term originating from the American Revolutionary War for citizens who were willing to take up arms against their British overlords at a minute’s notice. Similarly, the citizens of South Carolina mustered Minute Men militias in support of a Southern secession movement, warning in their constitution that “the election of a Black Republican President will be a virtual subversion of the constitution of the United States and submission to such a result must end in the destruction of our property and the ruin of our land.” By the end of November 1860, an estimated 20,000 South Carolina Minute Men drilled, marched in parades, and demonstrated throughout the state, harassing Unionists and showing their support for the South Carolina secession convention. Hundreds of thousands of Minute Men rallied throughout the South in the fall of 1860, often spearheaded by Knights of the Golden Circle. Meanwhile, in Baltimore, Maryland, the city’s National Volunteers militia had KGC members in positions of high authority.

Seeing military conflict between secessionists and federal forts as imminent, General Winfield Scott demanded that the sitting president James Buchanan reinforce Washington, D.C., and federal forts in the South. Buchanan did not want to aggravate Southern states while they held secession conventions, so he obstinately declined to reinforce federal forts. Between December 1860 and January 1861, over 20 federal arsenals and forts were raided by states’ rights Minute Men. Meanwhile, Buchanan’s Secretary of War, KGC member John Floyd, covertly used federal funds to smuggle small arms to the Minute Men.

January and February of 1861 were characterized by a series of close calls for the incoming Republican administration. A Washington, D.C., company of National Riflemen was disarmed after Colonel Charles Stone discovered that the men had coordinated with former Virginia governor and KGC member Henry Wise to arm 1,500 volunteers and overthrow the D.C. government. During his February whistlestop speaking tour, Lincoln’s Pinkerton detective bodyguards received news from a mole in a KGC Baltimore castle that the KGC planned to detonate a bomb when Lincoln visited the city. The next day, while Lincoln visited Cincinnati, an undetonated, defective bomb was discovered in Lincoln’s passenger train car. It is unknown whether that particular bomb was constructed by the KGC.

While Lincoln dodged bombs, Sam Houston feebly attempted to defuse the Secession Crisis in Texas. Houston spent the bulk of his time as President of Texas fervently lobbying the Jackson administration to annex Texas, assume their national debt, and enforce Texan land claims up to the Rio Grande. As Texas’s governor, Houston remained a staunch Unionist, to the chagrin of most other Texans. The KGC’s 8,000-Knight army harassed unionists, interrupted unionist speakers, and advocated for secession in the January 28 secession convention. During Texas’s convention, an estimated 11 out of 177 delegates were KGC members. The convention voted overwhelmingly to leave the union. The Texas KGC then focused on exporting their secession success to nearby Arkansas and Indian Territory. The Confederate government formed a Bureau of Indian Affairs in March 1861 and then dispatched KGC Commander Ben McCulloch and Indian-advocate lawyer Albert Pike (famed Scottish Rite Freemason and alleged KGC member) to negotiate an alliance with the Indian Nations and the enlistment of several regiments of Indian soldiers.

In January 1861, in Virginia, the KGC prepared to lead in the seizure of key federal military installations. Virginius Groner rallied a regiment of 1,000 KGC “Military Knights” alongside KGC member Henry Wise and his Minute Men. The two units drilled throughout December 1860, preparing to rush Fort Monroe in Norfolk Harbor immediately after Virginia seceded. Virginia secession convention decided in a 122–30 decision to stay in the union… unless the federal government provoked an armed conflict. Then, CSA cannons bombarded the federal Fort Sumter on April 12, pushing President Lincoln into authorizing the creation of a 75,000-man Federal Army to pacify the rebellious states. In response, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the creation of a 50,000-man Confederate army. As the Charleston Mercury stated: “Bickley’s forces are the most available nucleus for an army.”

While Davis built a nation and an army from scratch, George Bickley requested that the Confederacy also muster an army of 30,000 men in Texas to prevent rogue Mexican General Ampudia from invading the Confederacy’s southern border. Greer’s Texan KGC regiments, using Dr. E.L. Billings as an emissary, had concocted a plan to construct a railroad from the U.S. into Mexico, which would be used to transport an invasion force of 5,000 Knights into Sonora. Davis quickly uncovered that there was no imminent rogue Mexican invasion.

On May 7, 1861, Bickley sent circular letters out ordering that each of his KGC castle commandants muster his members into military companies and swear fealty to the Confederate government. Bickley estimated that he “has now 17,643 men in the field, and has no hesitation in saying that the number can be duplicated if necessity requires.” In the early stages of the Civil War, the KGC founded some of the first military units of the Confederate Army, but the KGC also engaged in sabotage against the North.

One company of New Orleans volunteers was named the Walker Guards, as it was largely composed of veteran filibusters of William Walker’s Nicaraguan campaign. KGC member Henry Wise organized the 60th Virginia Infantry Regiment, also known as Wise’s Legion, out of his KGC regiment Knights and other ex-filibusters. Wise’s regimental second-in-command was Charles Henningsen, William Walker’s Nicaraguan artillery commander. Almost every Texan unit consisted of KGC Knights. Notable Texan units either led by KGC members or consisting of KGC members included: the First Texas Infantry, the Lone Star Rifles, John Bell Hood’s Eighth Texas Infantry Regiment, Ross’s Texas Brigade (mostly KGC members and ex-Walker filibusters), and William Edgar’s Alamo Knights. An estimated 45 out of 55 of Texas’s KGC captains enlisted in the Confederate Army, 42% of whom were commissioned as officers of the rank of captain or higher. Other famous KGC-member Confederate officers include: Nathan Bedford Forrest, Joseph Shelby, John Marmaduke, and Jesse James.

As the war raged on, KGC membership lost its sheen. The KGC castles south of the Mason-Dixon Line ceased to function as organizations independent of the Confederate military; they were the Confederate military. Even George Bickley became a simple surgeon under the command of General Braxton Bragg.

In July 1863, Bickley applied for a permit to pass through Union Army lines so that he could visit his old home in Cincinnati, Ohio. Bickley pretended to be the nephew of “the famous General Bickley” to get through Union lines, but the officers who permitted Bickley to pass also requested that a detective tail Bickley. On July 17, 1863, the detective confiscated Bickley’s possessions, discovering KGC paraphernalia, KGC correspondence, and opium. Bickley was then apprehended and sent to prison in Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor without a trial.

Bickley attempted to bargain with his captors, insisting that he could act as a double agent on behalf of Unionists. He even insisted that he could convince his remaining KGC affiliates to support Lincoln in the upcoming 1864 Election. Bickley’s bargains were in vain. The KGC fell dormant in the South as the war raged on. Meanwhile, embers of the KGC continued to glow until the end of the war in the Midwest.

The Finale of the Final Filibusters

If the Knights of the Golden Circle disbanded in 1863, why does popular media today insist that they survived? Didn’t the KGC go underground and linger on after the Civil War? Didn’t the KGC organize John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of Abraham Lincoln? Didn’t the KGC hoard gold in anticipation of a second Civil War?

The answer to all of these questions is: “No.”

After the Civil War erupted, Abraham Lincoln suspended the right of habeas corpus and began prosecuting KGC members as Confederacy-sympathizing spies, often imprisoning them without trial. In April 1863, Philip Huber and the leadership of the KGC at Reading, Pennsylvania, were discovered, arrested, and imprisoned without trial. As a result of their persecution, the Northern KGC castles went underground, leaving only sparse evidence for modern-day historians to recover and record.

As George Bickley rotted in a Union prison, his Northern KGC castles reorganized as the Order of American Knights (OAK). OAK was a three-degree secret society located mostly in the Midwest from Ohio to Minnesota. Their purpose was to undermine the tyrannical Unionist federal government through logistical sabotage, promote insurrections in the Border States, and support Northern Democratic Copperheads. OAK was quickly infiltrated by Unionist spies and later rebranded itself as the Sons of Liberty. It is estimated that the SOL’s membership peaked at around 250,000 to 300,000 members, including former NYC mayor Fernando Wood and Ohio congressman and leader of the Copperhead Democrats Clement Vallandigham. As a means of smearing OAK as traitorous, Northerners invoked the SOL’s old Southern-affiliated KGC name as frequently as possible.

Alleging KGC affiliation in the North became a means of tarring and feathering one’s political opponents. Based on Confederate spy network documentation, the CSA maintained limited contact with OAK and SOL. However, paranoid Northern newspapers invoked the KGC as the archetypal embodiment of Yankees’ fears.

As entertaining as National Treasure: Book of Secrets may be, the film is pseudohistory. Although John Wilkes Booth, assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, was a member of the KGC, almost every historic event depicted in the film is fictitious. The KGC did attempt to assassinate Lincoln in 1860 but failed, and they disbanded in 1863. KGC survival theories are mostly nonsense. The KGC did not plan Booth’s assassination of Lincoln, and they probably did not directly bury gold bullion in anticipation of supporting the Confederacy in a second Civil War.

In early April 1865, Union forces engulfed Richmond, Virginia. The fleeing CSA government officials, including Jefferson Davis, were able to escort approximately $500,000 (roughly $10 million in today’s currency) in gold, silver, and bullion reserves out of the city. Six weeks later, Davis was captured in Georgia with only a fifth of the Richmond cache. Where did all of that gold go? Conspiracy-minded individuals of the post-Civil War era, as well as of today, theorized that the gold was buried in the hopes that it could be recovered at a future time by a revived Confederacy. The simple answer is that Davis spent most of the gold fleeing the Union Army and two Confederate naval officers stole $86,000 and fled to the U.K. The KGC was a post-Civil War boogieman, not a real underground organization preparing to launch a second Civil War.

To this very day, the Knights of the Golden Circle exist in the popular imagination as boogiemen. The ghosts of pirates past, waiting for the South to Rise Again.

“Wake up babe, the longest read since Tolstoy’s *War and Peace* just dropped.” 😂

Ok, but when are the Knights of the Silver Square going to filibuster the Maritimes and Canadian Prairies?