Return to East Palestine

The state of American rail, what happened, and what should have happened

The East Palestine derailment was a circus when news of a chemical explosion burst onto everyone’s social media feed on February 6, 2023. Pictures of a massive plume of black smoke were everywhere. Worse yet, there were unverified reports of carcinogens contaminating the entire Ohio River basin. I even presented my measured stance on the accident on an Old Glory Club livestream three months ago. Given four months of reports, hindsight, and my own independent water test, I want to put the minds of our dear readers at ease. The derailment did not contaminate the post-industrial American Midwest water drainage basin, but it did expose the inadequacy of the public relations department for one of America’s largest railroads.

Anatomy of Railways

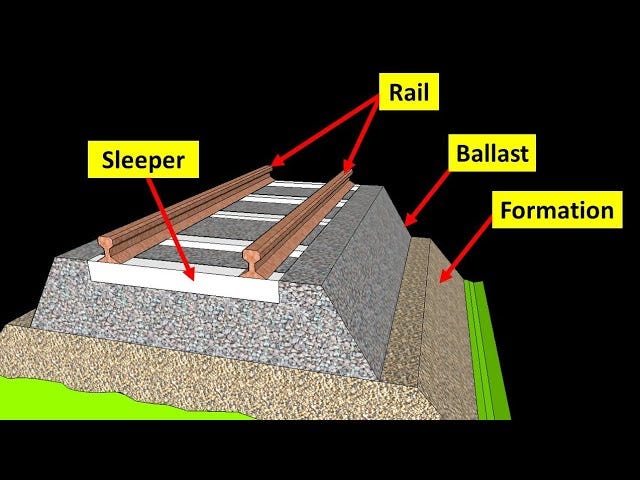

Railways are a network of tracks and rolling stock that transport either freight or passengers. Two parallel steel rails are fastened to sleepers that are perpendicular to the rails. These sleeper slabs can either be lumber planks or concrete blocks. Lumber sleepers are cheaper and easier to replace. Concrete blocks are rarer and more expensive than lumber, but they are occasionally used on tracks that expect heavier or faster-moving loads. Only one in four of sleepers need to be functional for trains to be able to run safely on rails. The rails and sleepers rest on ballasts, usually composed of some form of aggregate stone.

The distance between the two rails is called the gauge. In present day, most American railway lines use the Standard Gauge width of 4’8.5”.

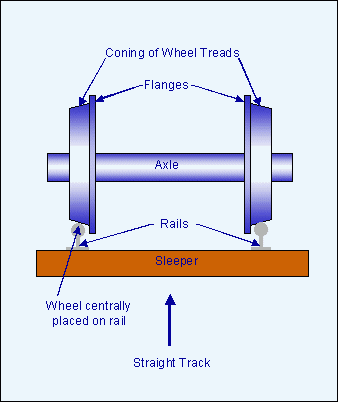

Rolling stock is the term used for the railway vehicles that roll on top of the rails. This term includes locomotive engines, freight cars, coaches or passenger cars, and maintenance vehicles. A locomotive hauling multiple cars is called a train. To generate forward thrust, locomotive engines rotate their wheels around an axle while the wheel treads rest on the rails.

Trains weigh A LOT. A single diesel locomotive engine weighs between 150 and 200 tons, and most railway cars weigh more than 100 tons. Trains usually consist of over 100 cars, making the total weight between 3,000 and 18,000 tons. Due to the massive momentum of modern trains, it can take a train over a mile to decelerate from full speed to rest.

A Brief History of American Railways

The history of American rail is one of early exponential growth, overextension via speculative bubbles, stagnation due to government overregulation, collapse, and then profitable retrenchment.

From 1826 to 1850, upstart American railway companies were founded with the purpose of connecting natural resource extractors (mostly coal mines) to canals, factories, and ports. In this early period, several smaller firms were created to transport passengers. The first passenger railways were novelty attractions, but they evolved to become an extremely lucrative and practical means of transporting suburban homeowners to their inner-city workplaces. The scope and design quality of these railways varied greatly. There were no standard design specifications for railway gauge widths, meaning that trains could only roll on the rails specifically made for them. Train operators would transport their freight for 50 miles on 4’0”-wide gauges and then stop, unload their cargo, and then reload their cargo onto a new train that runs on 5’0”-wide gauges for the next 50 miles. There were also several small speculative bubbles and incalculable train accidents. In spite of this chaos, in that 24-year span, 9,000 miles of railway track were constructed.

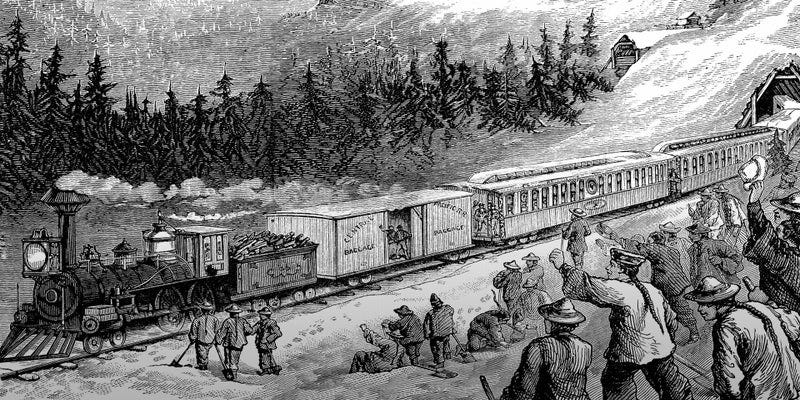

Between 1855 and 1871, the federal government supported several schemes that would financially incentivize the creation of a nationwide rail network. The most famous of these schemes was the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, which commissioned the Transcontinental Railroad, a 1,912-mile long railway from the Mississippi River to California. The feds required that the Transcontinental Railroad and all new rail infrastructure projects in the Reconstruction South use the new standard gauge of 4’8.5”.

In 1880, there were 93,000 miles of railways in America, and the railroads were the second largest national employer outside of agriculture. In 1890, there were 163,000 miles of rail, and the first electric railways were being introduced. The awe-inspiring exponential growth of the national railway network was met with concern by everyday Americans due to the predatory freight shipping practices, the consolidation of the railroads by several large corporations, and the overextension of the railway network. In 1887, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was founded to cap freight shipping rates. The Panic of 1893 burst the railway speculative bubble, resulting in the failure of a quarter of all railroad companies and the closure of 40,000 miles of railways. In the wake of the Panic, seven companies consolidated ownership of American railways. In 1916, the railroad network peaked in terms of mileage with a total of 254,036 miles of rails and 1,700,000 workers.

The American railway network was briefly nationalized during World War I, but the general trajectory for U.S. rail was that of gradual decline from 1916 to the 1970s. The ICC price caps slowly starved the freight network of capital incentives to invest in new rolling stock, and the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 funded the creation of a nationwide 46,800-mile network of modern highways. The proliferation of the automobile meant that suburban commuters no longer had to rely on the slower, unpredictable passenger rail network.

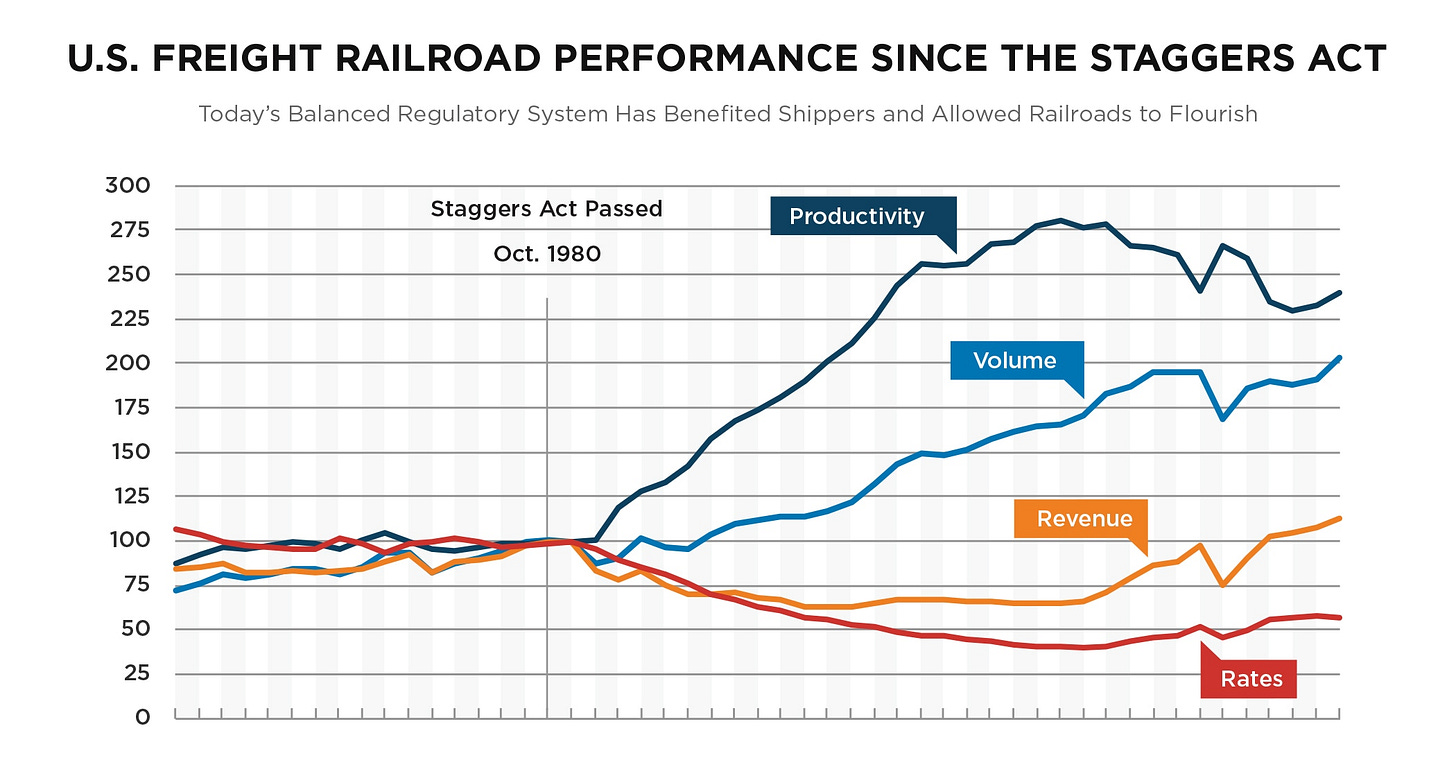

By the late 1960s, almost every railroad company filed for bankruptcy or was on the verge of bankruptcy. Inner-city passenger trains were unprofitable and falling apart as urban blight and crime waves terrorized commuters. In 1970, the Rail Passenger Service Act created Amtrak, a federally funded, quasi-public, for-profit corporation, by assuming control of dead or nearly defunct urban passenger railroads. Amtrak would quickly come to control half of all urban passenger railways. Today, Amtrak is the only passenger railway, outside of several small regional private passenger railways like Philadelphia’s SEPTA or Florida’s Brightline. In 1976, Congress passed the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act (4R Act). This Act created Conrail, another federally funded, quasi-public, for-profit corporation, for the purpose of keeping the freight railway lines of the defunct private Penn Central Transportation Company in-service. The 4R Act was also the first of four Acts of Congress to deregulate the railway industry. With the passing of the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, the ICC was effectively defanged and no longer able to cap freight prices, and federal safety and environmental regulations of American railways were scaled back.

After 1980, there was a great retrenchment of the American rail network. Two railroads, Norfolk Southern and CSX, took control over almost all railways east of the Mississippi River, and two railroads, BNSF and Union Pacific, took control over almost all railways west of the Mississippi River. Unproductive tracks were shut down, and Conrail was fully privatized. Today, half of Conrail’s stock is owned by Norfolk Southern, and the other half owned by CSX. Conrail is a rump railroad that consists of all of the unproductive, expensive, and inner-city railway lines that CSX and NS do not want to own directly.

Many democratic socialist ideologues bemoan the corporate consolidation and deregulation of the American railways. However, if one actually looks at the productivity of the railways as a whole and productivity per worker, American rail has bounced back since the doldrums of the 1960s. Railways charge lower rates to ship more volume of freight while using significantly fewer employees, at the cost of the federal government giving four railroads almost complete sovereignty over the industry.

Since the 1990s, nearly every railroad has adopted Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR), a logistical project management method of optimizing route efficiencies, cutting the number of locomotive engines, and increasing the number of railcars per train. This practice means that it costs people less to ship freight over the rails. As a rule of thumb, freight rates go down the longer the trains are. PSR has the downside of being incredibly taxing on railway employees, making train derailments more dangerous when they happen. Under PSR, train conductors have to work longer shifts and oversee longer trains.

The length of trains matters from a safety perspective because when trains travel around a bend, conductors should be able to look at the cars behind them and check to see whether there are any problems with their cars’ wheels. Conductors cannot see cars further back if the trains are longer than 100 cars. To make up for the lack of conductor visibility, railways use hot box detectors and security cameras. Hot boxes use infrared sensors to measure the temperature of train car journal bearings, the components that hold wheel axles in place. If the hot box detects overheating axles, the conductor receives immediate notifications and can act accordingly. If train axles overheat due to manufacturing defects or wear and tear, the wheels can fall off the rails and cause the entire train to careen off the tracks. Whenever trains inadvertently go off of their tracks, the incident is referred to as a train derailment.

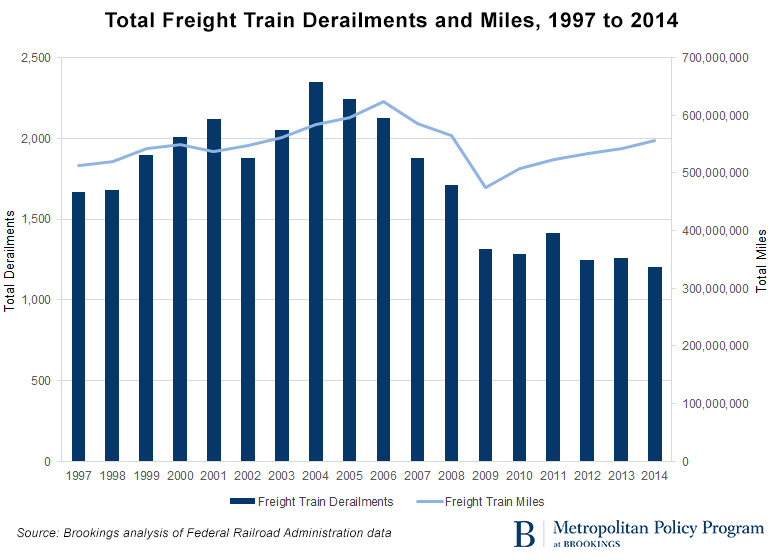

The number of train derailments has declined over time in spite of maintenance and staffing cost-cutting measures. Most train derailments are minor and result in few cars going off of their tracks. Even when major derailments occur, they are usually handled professionally and ignored in the media. Train derailments are not flashy news. There are over a thousand derailments happen each year, a little over three derailments per day, but almost none have explosions or chemical burns.

Timeline of the East Palestine Derailment

On February 3, 2023 at 8:12pm, Train 32N, a Norfolk Southern freight train of 149 cars, was spotted by a security camera with several of its wheels on fire.

At 8:54pm, according to the National Transportation Safety Board, the train passed over a hot box detector at milepost 49.81, east of East Palestine, Ohio, and sent the train crew a critical alert message that a train axle was 253°F. The crew immediately applied the train’s emergency brakes, but by that point, it was too late. The 23rd car of the train, the car seen in the footage with its axle on fire, flew off the tracks. Thirty-eight of the train’s cars derailed just east of the town of East Palestine (population: 5,000). Eleven of the derailed cars contained hazardous materials including vinyl chloride, butyl acrylate, and isobutylene. Another 12 cars did not derail but were found to have been singed by fire.

First responders arrived at the crash site very shortly after the derailment. No conductors or civilians were harmed during the crash.

At around midnight, members of the U.S. Environmental Protective Agency (EPA) arrived at the crash site. They immediately took air quality samples and monitored the site for volatile organic compounds.

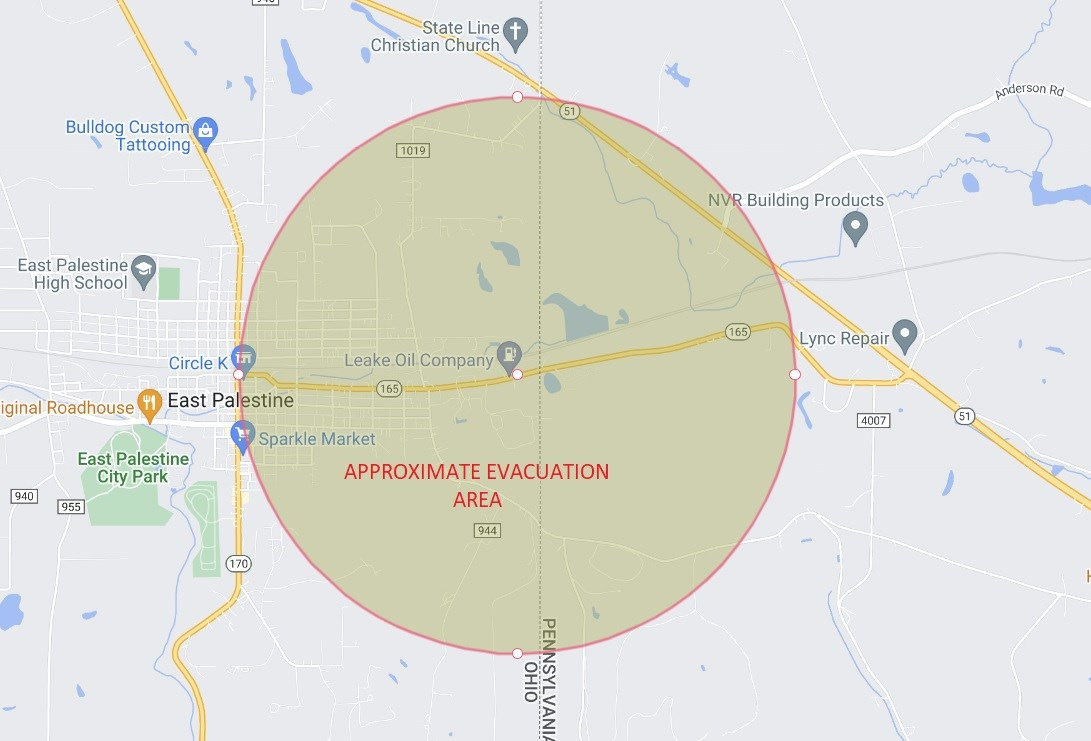

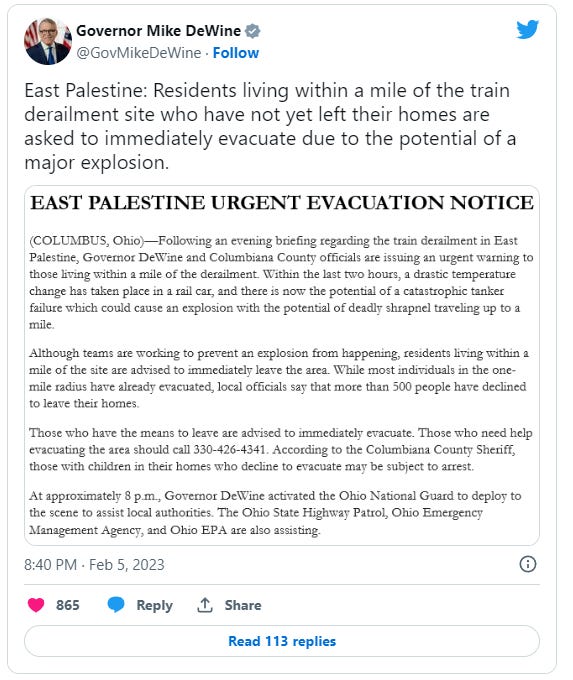

Due to the presence of hazardous gases in unstable crashed train cars, first responders started knocking on the doors of the 2,000 residents who lived within a one mile of the accident, urging them to evacuate. East Palestine High School was made into a makeshift evacuation shelter.

Early in the morning of February 4, the EPA instructed contractors to install underflow dams the ensure that no hazardous liquids could leach into the nearby Sulphur Run or Leslie Run streams.

By February 5, the derailed train cars were still on fire and had the potential to explode at any moment, hurl shrapnel into nearby buildings, and release toxic gas into the air. If there was an explosion, it would have turned the hazardous liquids into hydrogen chloride and phosgene gas. In its liquid form, vinyl chloride is extremely cancerogenic. When set on fire or exposed to sunlight, vinyl chloride breaks down within a few days into hydrochloric acid, formaldehyde, and carbon dioxide. Throughout the day, EPA employees tested the conditions of the nearby streams and the East Palestine water treatment plant’s water, finding no contaminants.

At 8:00pm, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine activated the Ohio National Guard to assist local law enforcement in removing the remaining 500 residents within the 1-mile radius who had not fled. None of the cars containing vinyl chloride had released any hazardous material. The EPA confirmed that they did not detect any contaminants of concern in the air. Sometime earlier in the day, the National Transportation Safety Board employees arrived at the site to document the conditions of the area within the 1-mile radius.

On February 6, Norfolk Southern made the decision to drain the vinyl chloride tank into a trench and light the hazardous material on fire, so as not to let the fires continue to increase pressure within the tanks and potentially cause an unexpected catastrophe. It was decided that a controlled burn would be safer than an uncontrolled explosion.

At 3:30pm, emergency responders controlled the release of the hazardous liquid chemicals and proceeded to burn them. A plume of black smoke could be seen from many miles away. The EPA detected low levels of phosgene and hydrogen chloride, and the ten remaining residents who had refused to evacuate complained of a faint chlorine smell. The contained fire continued for several hours.

On February 8 the evacuation order was lifted. Residents reported feeling headaches and respiratory problems due to the lingering chemicals. Residents continued to smell chlorine and reported experiencing increasingly adverse symptoms, including a family that got rashes and nausea after only spending 30 minutes in their home upon returning.

By February 10, the EPA conducted 500 residential air screening appointments and continued to investigate nearby streams for contamination.

On February 15, municipal politicians and Norfolk Southern officials held a town hall to alleviate residents of their water contamination concerns. That same day, Governor DeWine published an East Palestine water quality update.

For the next two weeks, the EPA continued to monitor water quality conditions and test indoor residential air quality. By this time, Norfolk Southern provided $2.4 million in direct financial assistance to families and $1 million to municipal emergency support personnel. Although municipal tap water was safe enough for the Norfolk Southern CEO and Ohio governor to drink, NS was unable to find a safe place to dispose of the contaminated soil that had been used as a trench during the controlled burn. The EPA threatened to fine Norfolk Southern if they did not remove the contaminated soil from the premises.

My Site Visit and Water Testing Results

I arrived in East Palestine at around noon on February 25. My goal was to take water samples from the nearby State Line Lake and see what the crash site looked like. I detailed what I saw in this Twitter thread.

The area marked in red was the site of the train derailment. I initially wanted to take water samples from the three locations marked in blue, but unfortunately, the pond in the southwest of the map was located on private property. That pond was located up a steep hill, far from the crash site. I did not believe that it would have been contaminated by spilled chemicals.

When I arrived at the town, E Taggart St, the main road connecting the town to Pennsylvania, was blocked off by Norfolk Southern employees.

Several non-railway onlookers were hanging out next to the blockade. They had been observing the site conditions and explained that every nearby landfill rejected Norfolk Southern’s plea to take the contaminated soil off of the crash site. There were several dump trucks waiting to take away the soil, but no truckers in sight.

I then proceeded to take water samples from the nearby State Line Lake and from a pond south of the lake. I spotted ducks splashing in the lake, indicating that wildlife was not disturbed by the scent of chemicals several weeks after the crash. I was cautious to avoid getting any water on my hands or feet, so I wore chemical-resistant nitrile gloves and chemical-resistant rubber boots. I was not concerned about breathing in hazardous chemicals because it had been raining for two days before I arrived at the town. Any lingering hazardous chemicals in the air were either dissolved by the sun or absorbed by the rain.

I then drove around the blockade and tried to get a water sample from the southwestern pond. I was not able to get that sample, but I was able to get a nice view of the crash site from the hill overlooking the railway.

Disappointed, I decided to get lunch from the McDonald’s that Trump had visited the prior week.

I initially wanted to ship my water samples to a subversive mad scientist friend who will remain nameless. This friend said that he would not test it himself but would send the samples to his sister who worked for a chemical testing lab. This friend’s sister “chickened out,” and he did not want to test the samples, so I decided to test them myself.

I purchased a water testing kit to measure the samples’ pH and chlorine levels. I took two water samples from State Line Lake and one sample from the pond south of the lake. The results for the pond sample were skewed because I scooped up trace amounts of dirt and organic matter. As far as I could tell, the water samples I took could have come from any other pond in rural Ohio. The pond’s pH was about 6.8, slightly more acidic than a pond should be, but I had expected that because it had trace amounts of soil. The Lake’s samples both had pH levels of between 7.5 and 8.0, normal for ponds. The pond’s measured total chlorine was about 1 ppm, but the two Lake samples both had roughly 3 ppm, moderately high concentrations for ponds in nature, but expected in post-industrial Ohio.

Next door to East Palestine, Ohio, is the Monongahela River, the second most polluted river in America. Due to Pittsburgh’s historic steel industry, East Palestine was downriver from some of the worst contaminated water in the country. After the East Palestine crash, I saw several videos of Ohioans seeing oil sheens in their local streams. The real threat to the lives of Ohioans is not new train crash chemical spills; it is the present condition of their post-industrial water supply.

What Norfolk Southern should have done

In late May, I had a chat with a CSX local claims representative at the site of a soil slide. A hill collapsed due to heavy rainfall, and debris ended up on the railway. He and I quickly struck up a conversation about East Palestine. From his public relations perspective, every decision Norfolk Southern made was incorrect. Official railroad policy is open and honest transparency with the local press, to accept full legal responsibility and to throw exorbitant amounts of money at anyone inconvenienced by the railroad. The first major mistake Norfolk Southern made was to avoid the press. It took NS several days to hold a press conference, and when they did host one, they did so in a cramped space and delayed it by several hours, angering journalists.

The second mistake NS made was to leave the evacuation response to the local municipal emergency responders. Official railway policy is to book hotel rooms for anyone inconvenienced by railroad activities. Removing residents with iPhone cameras from railroad explosions and removing residents from potentially breathing in toxic railroad fumes would have saved Norfolk Southern from the class action lawsuit they are having filed against them. The CSX legal rep added that NS should have given each East Palestine resident a $200 Walmart gift card to buy clothes and supplies. It is also standard railroad policy to buy all land affected by railway accidents. This measure would have been costly, but it would have also shown Norfolk Southern as proactive instead of reactive, and it would have demonstrated goodwill to the residents.

The third mistake NS made was to neglect to inform the public about the giant cloud of black smoke that they were intentionally going to cause. Instead of preemptively controlling the narrative, the railroad let disgruntled journalists and conspiratorial denizens of the Internet run wild with speculations. Infrastructure firms are not used to interacting with the public. If NS had simply held an emergency press conference to inform the public that vinyl chloride had not contaminated the town’s water supply before the controlled burn, a significant amount of panic could have been averted.

Train derailments are not new, and railway chemical spills will continue to happen as long as there are railways. According to most railroad statistics, freight transportation is getting safer each year. Nonetheless, railroads need to adapt to the new social media atmosphere that values corporations that proactively control the narrative of ongoing events. The CSX employee pointed to the Graniteville chlorine spill of 2005 as a case study for a rapid railroad cleanup response and public relations management. In that particular chemical spill, two Norfolk Southern trains collided due to a faulty railroad switch and derailed; and chlorine gas was spilled on the small South Carolina town. Nine people died on January 6, 2005, several hundred people were hospitalized, and one more person passed away over three months later due to chlorine inhalation. NS spent $40 million in responding to the emergency. They rented out entire hotels to evacuate the town and spared no expense to ensure that all damaged property was made whole by generous reimbursements. For the next decade, NS was embroiled in several environmental and damages lawsuits. In the long run, the railroad’s early concern for the well-being of the affected residents and the thoroughness of their cleanup saved Norfolk Southern from any serious fines or litigation.

When chaos strikes and you are responsible for ensuring the safety and sanity of thousands, moderation is never the answer. People need a narrative. People need heroes. When professionals quietly try to solve problems on their own, put in the bare minimum of effort to mitigate concerns, or neglect to take action, insanity will creep in from opportunists who want to capitalize on confusion. That is the real lesson of East Palestine.

Sorry for not being able to test the water!

Thank you for a well researched and interesting article. I was not paying attention to the news when this story broke out, so this was a good outline of the issue for me.