American Culture?

In the time I have spent interacting with people outside America, there is always a phrase that inevitably crops up. The refrain usually goes as follows:

American culture? Ha! What a joke! Americans have no culture!

Upon my first time hearing this, I was certain it was just a joke. There is no way that anyone could believe that a group of people separated from the rest of the world with a distinct religion, heritage, and history could be cultureless for five centuries, right?

Well, against all reason and good judgment, this sentiment is common. I would like to address it in a very practical manner. We do not have to worry about any one particular group or person or even argument. I will not be pontificating as to the nature of culture or making checklists for what makes a real culture. No, instead I have been handed the perfect opportunity to simply showcase one of the West’s richest cultures.

Ocean Wide and Ocean Deep

“American Culture” is such a gargantuan topic that I could not satisfactorily compile it into a set of encyclopedias, let alone a simple article. Given this reality, we will simply be focusing as much as possible on one aspect of one part of this culture, specifically the development of American classical music.

American classical music? Why this? Surely if American music is to be discussed, we should pick spirituals or ragtime or jazz or rock. Classical music, as we were all taught in schools if at all, is exclusive to the European continent. More to my insanity, we will actually be starting near the end of the Baroque Era, long before America was even an independent polity.

I have good reason for starting as far back as the Baroque Era. This earliest form of American musical sophistication will form half a foundation for all other American music to build atop (the other half being British folk songs).

In order to understand the rest of American music, we first need to understand when music became exoteric, spreading from the sole domain of organists and clergymen.

John Tufts and the Puritans

We will start at the first uniquely American advancement in music, in particular at the publication of An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm Tunes in 1721 by John Tufts, right at the end of the Baroque Era. An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm Tunes was the first American book published with the intent to bring music into the day-to-day lives of Americans. Other books with similar intent had existed before this, but none were American in origin.

An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm Tunes makes its purpose clear, beautifully stating that it is “For Use, Edification, and Comfort of the Saints in Publick and Private, especially in New England. Let the Word of God dwell in you richly in all Wisdom, teaching and admonishing one another in Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Sings, singing to the Lord with Grace in your Hearts.” The book contains all 150 Psalms, most songs contained in the Old Testament from Moses to the Song of Solomon to the prayer of Jonah, and most songs of the New Testament.

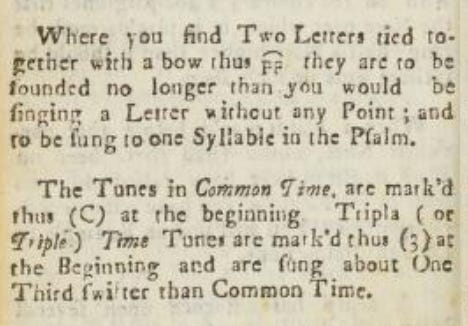

Every single song is arranged by meter, and at the back of the book is a collection of tunes for which to chant or sing these songs. Before these tunes, John Tufts includes a short explanation of not just chanting and singing, but of singing in general, a key innovation of this book. Tufts explains flats, sharps, lengths of notes, time signatures, clefs, syllables, measures, and any other basic musical concept.

A Distinct Culture

For the first time, all Americans, not just musicians and clergy, had the opportunity to learn music. Notes and staffs no longer referred to pieces of paper and walking sticks. Rather they were vital building blocks for Sunday services, midweek meetings, and home homilies.

Psalm chanting especially would become very popular, easily spreading outside Puritan New England into the rest of the colonies. Other churches (that allowed music) began fitting Scriptural songs and chants into their services.

This early unity would contribute to the development of a distinct American culture. The greatest effect would be seen in the Great Awakening, which saw great success due to a common form of worship that American congregants and parishoners loved, regardless of denomination or colony.

Well said

Good article Turnip. Studying the music of a people is a good way to study their culture, as music is something everyone can understand to some degree or another, but also something that every culture does slightly differently.

Are you familiar with Sacred Harp singing? It’s more of a New England/Old South thing than an Oklahoma thing, and something I associate less with Lutherans than with Appalachian congregations in the east, though it’s becoming more widespread across the country. It’s a singing tradition that goes back to the first half-century of American independence and uses shape note notation instead of the conventional key signatures. It’s very beautiful, very Protestant, and thoroughly American.