The battle of Midway is a quintessential American Naval Victory. The 81st anniversary of that battle is this week. It represents the pinnacle of American military achievement as well as the typical Anglo-American “can-do” attitude. This battle, which took place only six months after the disaster at Pearl Harbor, was the decisive Naval victory in the pacific theatre and set the tone for the rest of the war. This article will attempt to analyze the battle according to the U.S. Army’s Nine Principles of War. To summarize these principles briefly, they are: Economy of Force, Unity of Command, Mass, Maneuver, Security, Simplicity, and Surprise.

Naval doctrine up until this point had been focused on delivering a singular, decisive engagement as per pre-war plans such as War Plan Orange. However, naval thinking over the previous two years of war was required to adapt to the usage of aircraft deployed from aircraft carriers, which made surface engagements between ships in sight of each other no longer the decisive form of naval warfare. Whilst there was no one single engagement which decided the war in totality for the naval realm, Midway was decisive in its outcome because the Japanese were unable to sink more than one of the American carrier forces and lost four carriers themselves.

It must be mentioned that the battle of Coral Sea, which had taken place in the Coral Sea southwest of New Guinea and Northwest of Australia, had taken place only a month earlier. It was in that battle that naval forces engaged each other in an actual high seas battle without ships being in sight of each other during the fighting. The outcome of Coral Sea determined the order of battle for both the Americans and Japanese during Midway. Whilst the United States had lost USS Lexington, the Japanese had lost the escort carrier Shoho and suffered damage to the carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku. This damage meant that The Japanese could not use the Shokaku or Zuikaku for the Midway campaign. USS Yorktown, which had taken damage at the Battle of Coral Sea, was repaired enough to take part in the Midway battle, providing a critical boost in carrier-launched airpower for the battle, which ensured that the United States Navy had numerical parity in carriers for the actual forces engaged in the battle. So, instead of having a numerical advantage after Coral Sea of seven total carriers to the United States’ three total carriers including the damaged Yorktown. the Japanese only committed to battle four carriers against the American three.

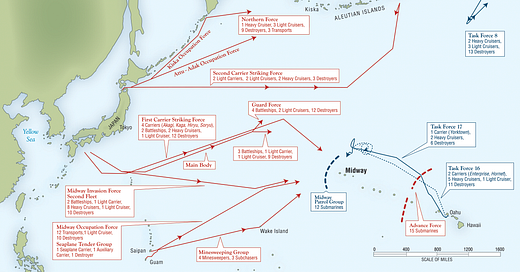

Furthermore, the Japanese did not realize that they were operating without the benefit of surprise: American code-breaking efforts had understood the Japanese operational plan for Midway long before battle was joined. This was overly complex, splitting the Japanese fleet into multiple parts. They were spread out so that they could not provide mutual support. This could have worked as a plan, but only if the United States was completely unaware of Japanese intentions. It relied on multiple strikes towards the Aleutians as feint attacks obscuring the true Japanese goal. So, no security for the Japanese forces, nor the element of surprise.

Thus, we can see that in addition to the lack of security and surprise for the Japanese forces due to their operational planning being known to the U.S., they failed to sufficiently mass their forces to accomplish their objective of invading Midway Island. The American Task Forces 16 & 17 at least were close enough to be able to provide support to each other. To a certain degree, Admiral Yamamoto was delegating this action to Admiral Nagumo Chuichi. So, the command on the Japanese side was somewhat disunified because the man carrying out the battle plan did not create the plan. The Admiral who created the entire plan for the conquest of Midway was not present for the fighting.

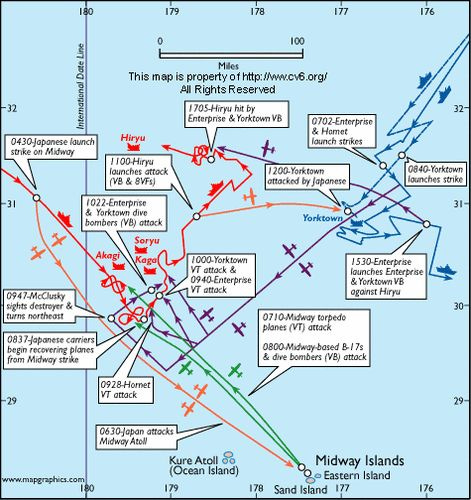

On the 4th of June, 1942, Admiral Nagumo launched a dawn attack on Midway Island with 108 of the planes in his strike force, losing 38 planes in the attack. Midway’s airfields were still operational, requiring a second strike. Nagumo had retained 93 planes in reserve, which were armed with armored piercing bombs for usage against ships because he was still unaware of the location of the American carriers. He therefore ordered the re-arming of these remaining 93 aircraft with fragmentation bombs for a second attack on Midway. At 0728, he received a report from a scout plane that there were American ships to the northeast. He hesitated for ten minutes and halted the previously ordered change-over of ordnance. During this time, American bombers from Midway launched an unsuccessful retaliatory attack on the Japanese carriers. He then received a report from the scout plane that the American ships which had been sighted included carriers. Nagumo now had to make a snap decision: should he launch the attack at once, even though his 93 reserve planes would have no fighter cover? Or should he wait for the return of the planes which had originally attacked Midway Island, and launch a full strike?

He decided to wait. His crews worked from 0830-1030 refueling and re-arming his returning planes. However, the American naval forces under the command of Admirals Spruance and Fletcher decided to launch the attack of their planes. They too had a big decision to make: whether to wait or launch immediately despite being outside the optimal range of 100 nautical miles. Spruance decided to launch at 175nm at 7:00am with Enterprise and Hornet’s nearly full aircraft loadout: 98 bombers and 20 fighters, retaining only a few fighters for defense. Admiral Fletcher, preferred to wait, and launched at 8:30am. However, the American planes which had launched did not find the Japanese force initially, because Nagumo had turned to the Northeast by 0915, leaving only empty sea in his wake. However, 15 Devastator torpedo bombers of Torpedo Squadron 8 from USS Hornet, led by Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron found the Japanese carriers, despite being completely unsupported, he ordered his torpedo bomber squadron to attack. They were annihilated by Japanese Zero fighters. None of these 15 bombers survived. Next to arrive on scene were the Torpedo bombers from Yorktown and Enterprise. They suffered a similar fate. Of the 41 Devastator torpedo bombers launched, 35 out of 41 were shot down. None of these Torpedo bomber attacks scored a single hit.

Just as the last of the Devastator torpedo bombers were being shot down, the American dive bombers appeared at fourteen thousand feet. These bombers would change the course of the war. Thirty-seven Dauntless dive-bombers led by Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky made this next attack and had previously been part of the group of aircraft originally unable to locate the Japanese carriers. They had been launched from the USS Enterprise. They guessed the likely location of the enemy carriers based off of the course followed by a lone Japanese destroyer, extrapolating the direction of travel that the carriers would likely have taken. At 10:25, these dive bombers found a Japanese fleet whose fighter cover was occupied temporarily with the remaining torpedo bombers. The rearming and refueling of Japanese planes were nearly completed by that point, but this was a terrible time to receive bombs, penetrating the wooden flight deck whilst fuel lines and ordnance were not stowed away. The Japanese carriers Akagi and Kaga began sinking in minutes. The dive bombers from Yorktown then arrived and began attacking the Soryu, which also sank as a result.

Despite this, Nagumo launched the planes from his remaining carrier Hiryu. These planes scored 3 bomb and 2 torpedo hits on the jury-rigged Yorktown, causing her to have to abandon ship, but yet she still stubbornly remained afloat. Despite the loss of Yorktown, the American planes again found the Japanese strike force and sunk the remaining carrier Hiryu later that the afternoon. All four of Nagumo’s carriers, the pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy, were sunk. The final fate of the Yorktown was not actually to be sunk by carrier aircraft, but by a torpedo salvo launched by IJN submarine I-168 as it was being slowly towed back to Pearl Harbor, along with the USS Hammann, a destroyer who was alongside the Yorktown as she was being towed.

So much for the battle, now for some strategic and tactical analysis. As has been mentioned, the Japanese lacked the element of strategic level surprise and security because their plan was known to the U.S. through broken encryption. Second, they lacked a simple plan, which had spread out their forces over thousands of nautical miles, which meant that they could not support each other. The U.S. military knew where the Japanese would attack, which forces they would likely attack with, and roughly when they were likely to attack. The Japanese did not sufficiently mass their forces for an attack. Strategically, this is an attempt to use economy of force and split up a smaller American fleet, engaging only with what was tactically necessary to achieve victory. Rather, what the Japanese should have done, given their true objective at Midway, was to centralize all their forces and meet the U.S. Navy in battle with overwhelming superiority of numbers. The Americans massed the carriers they had and did an excellent job of getting the Yorktown just repaired enough that it could participate in the battle. This gave them the number of carriers required to actually effectively engage the four Japanese carriers. Without Yorktown, the USN would have been outnumbered two-to-one in carriers at Midway. If the Japanese had massed their forces and the Americans could not get Yorktown back into action, the ratio of carriers would have been seven-to-two.

In terms of maneuver, the Japanese did make an interesting decision to attack Midway Island before they had located the American carriers. Once aircraft were launched, they had to be recovered once the attack was completed. This left the Japanese vulnerable to carrier-based attack, which is more maneuverable than island-based aircraft. An island is indeed an unsinkable aircraft carrier, but that means its static nature should be used against it. The Midway based bombers launched against the Japanese carriers after the initial Japanese attack did not do substantial damage, so it is fair to say that Nagumo's initial focus on Midway was somewhat misplaced. Admiral Spruance’s aggressive launch of the planes under his command resulted in high casualties for the squadrons involved, but also ensured the sinking of multiple enemy ships, thus ensuring victory.

The decisions for the commanders of either side, and the courage of the pilots involved proved decisive to the outcome of the battle. They represent the highest point of American Naval prowess. They are worthy of remembrance by true Heritage Americans.

References:

Symonds, Craig L., Historical Atlas of the U.S. Navy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1995). 146-151.

U.S. Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-0 Operations. (Washington DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, February 27, 2008).