Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Manila Bay (1898). I won’t focus as much on the tactical analysis here, so if you want my in-depth analysis, you can check out my take on my personal Substack. Needless to say, naval combat in the Pacific was a uniquely American experience in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially considering how the major actions in which the U.S. fought were strategic as well as tactical victories. No other country has such a storied lineage in the last 130 years on the high seas. The names ring out as an honor roll: Pearl Harbor, Coral Sea, Midway, Leyte Gulf, etc. Manila Bay counts as part of that storied lineage because the Spanish-American War was the initial moment of imperial muscle-flexing by the United States.

Part of historical revisionism’s purpose is to ask additional questions about the given historical narrative for a certain time period. The Spanish-American War can also be recontextualized in such a manner. As an aside, I think that, for our purposes, Midway should be celebrated over D-Day in the future because of how stunning of an underdog victory it was, and because it refocuses the Pacific theater into a more prominent position compared to the European strategy of the (Atlantic) Anglo-American powers. It refocuses on the United States in its true role as a power which had a largely Anglo elite at the time — that is to say, as a maritime power.

So, how does this relate to Manila Bay? Well, the usage of Midway as a victory over an ascendant Asian third-world power by the U.S. can be applied as a pattern. Is the Battle of Manila Bay representative of a victory of a democracy over a tottering and decrepit Spanish Empire? Was it simply a “decolonization” project against a European power? Or was it more likely a younger “European” power outside of Europe flexing its muscle in the scramble for territory during the halcyon days of the colonial period? Was it simply a “Nordic” Anglo assertion against a Hispanophone power? The evidence of the American and European attitude a few years later during the Boxer Rebellion is instructive. America was perceived of as a colonial power in its own right and was not perceived of as lacking Europeanness in any way.

No, this idea that America was against Europe is indeed a post-mid-20th-century view. Despite the Spanish-American War setting precedent in many ways for the patterns which governments and media adopted to control the emotions of their populations, this was not the messaging at the time. Probably only the Marxists of the period considered it as such. No, that is the narrative which was invented to turn the period of Western dominance of the world on its head. It required the “European” nations and peoples to fight each other. The easiest way to do this was to play up colonial rivalries about which country had the most prestige and to maximize their petty hatreds until they boiled over into real conflict. In this way, one could recontextualize these intra-European conflicts into a story about who exactly had the leadership position within Western Civilization. That position of the dominant power, the leading core-state, changes within civilizations over time.

The battle itself is instructive of the necessity to combine the strategic, operational, and tactical levels of military operations in order to have these elements work toward the same purpose. The United States Navy post-doldrums era was rather top-heavy, with slow promotions for officers. This created situations unheard of in volunteer militaries. Men would reputedly stand bridge watch with their own sons, or at least men who could be young enough to be their sons. This naturally created a maturity and professionalism within the USN, with plenty of institutional knowledge. One criticism of a “leadership only” approach is that it tends to ignore the competency of mid-grade leadership in favor of senior leadership and executive roles. It tends to meld the necessity of overwhelming competency in the commanding officer and ignores his true purpose: that of vision and direction. Needless to say, the USN at the time had plenty of competency at the mid-level, with extremely experienced people who had been in service in some cases for an entire career as a lieutenant. Despite the advanced age of some of the junior officers, their morale was extremely high, as one can imagine. Fighting a high-seas battle would have been the high point of their careers, a capstone event. Victory would grant honors more than any commendation ever could.

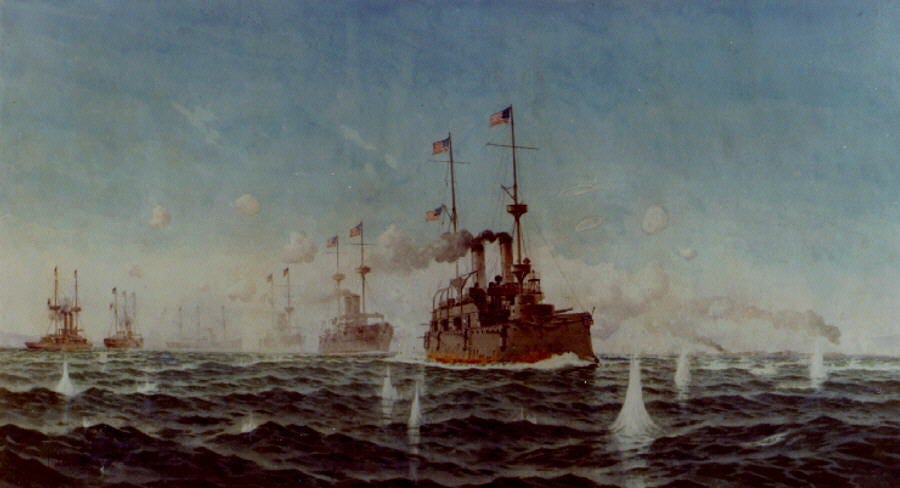

Commodore George Dewey was obviously a man with the requisite qualities of leadership. His men trusted him. The squadron under Dewey did not initially have the requisite logistics for a campaign. For example, the beautiful American paint job which would become famous during the “Great White Fleet” of Teddy Roosevelt had to be painted over. The brilliant white and gold of peace had to be replaced with wartime haze gray. Painting an entire ship is a huge, labor-intensive undertaking. It can’t really be done quickly, unless the weather cooperates. Furthermore, they had to get rid of flammable materials such as wood furniture and fixtures before going into action.

Second, the Pacific squadron under Dewey was stationed in Hong Kong. Since the British would remain neutral in the conflict, the American squadron in Hong Kong had to relocate to avoid a diplomatic incident. Hosting a belligerent party in port during a conflict, providing supplies and fuel etc., is usually the act of a hostile power. So, to avoid unnecessarily embroiling Britain in the conflict, the Americans had to relocate thirty miles north to Mirs Bay. China apparently turned a blind eye despite also being neutral. Coal and supplies were difficult to come by because many nations had ships in Hong Kong. This left Dewey with the necessity of having to contract out to the British ships Nanshan and Zafiro for collier and supply ship duties.

As we can see, there was a lot of work involved just to get into the fight. Without Dewey’s open approach to ideas provided by the officers beneath him, he might not have been as successful. If an idea was sound, it was taken onboard during the planning process.

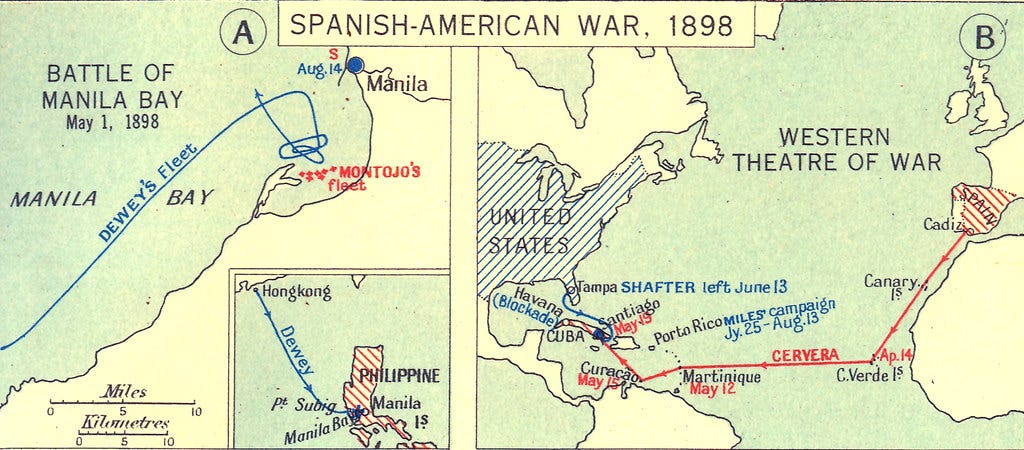

As for the actual action itself, Dewey’s ships first went to the expected location of the Spanish fleet at Subic Bay. The Spanish commander, Admiral Patricio Montojo, had elected to move his fleet to Cavite inside of Manila Bay rather than stick around in Subic Bay. This was because the large-caliber fortress guns which were supposed to be installed at Subic Bay had not been. Subic Bay was also deeper, which precluded the possibility of rescuing crew in the case of disaster.

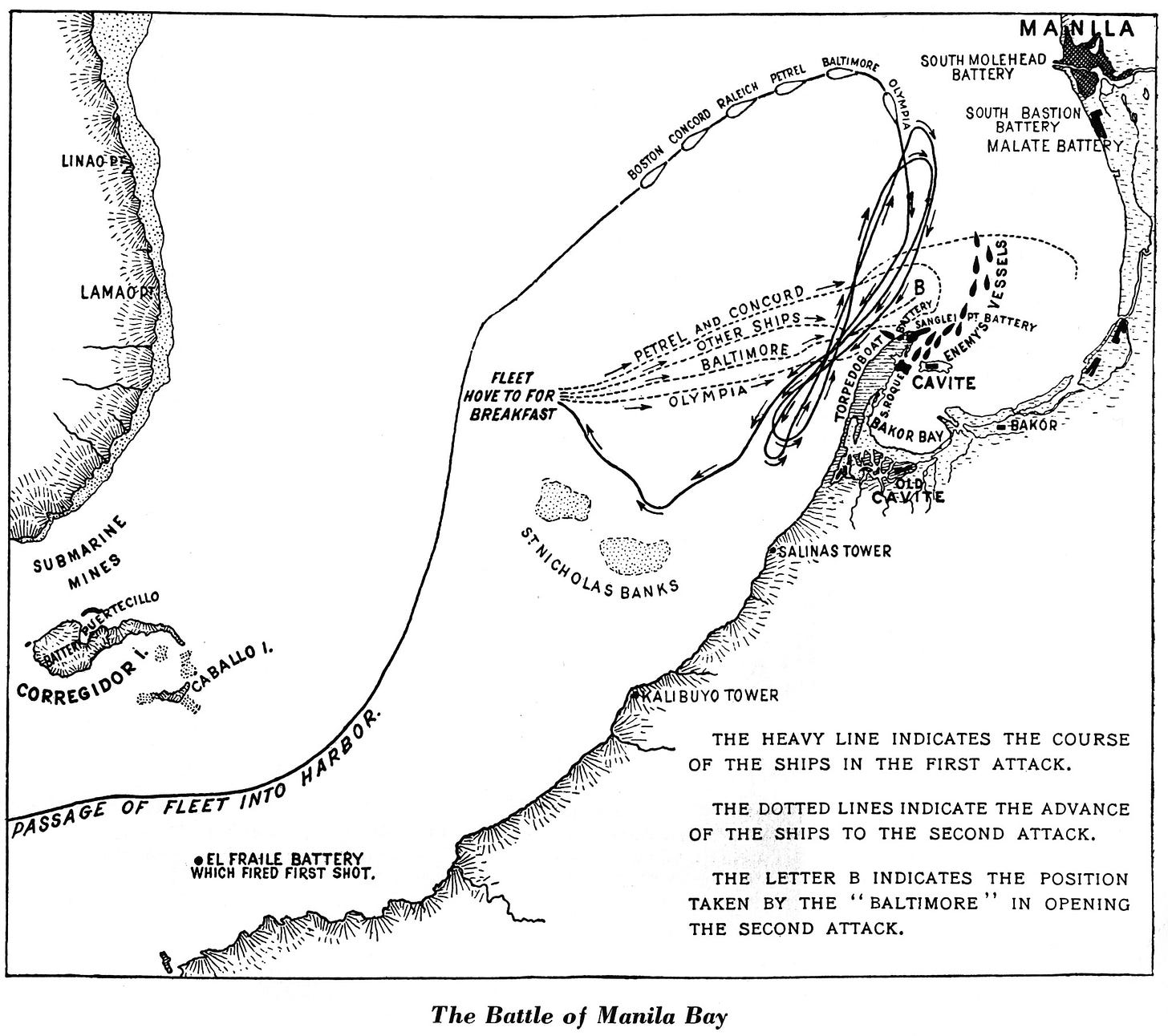

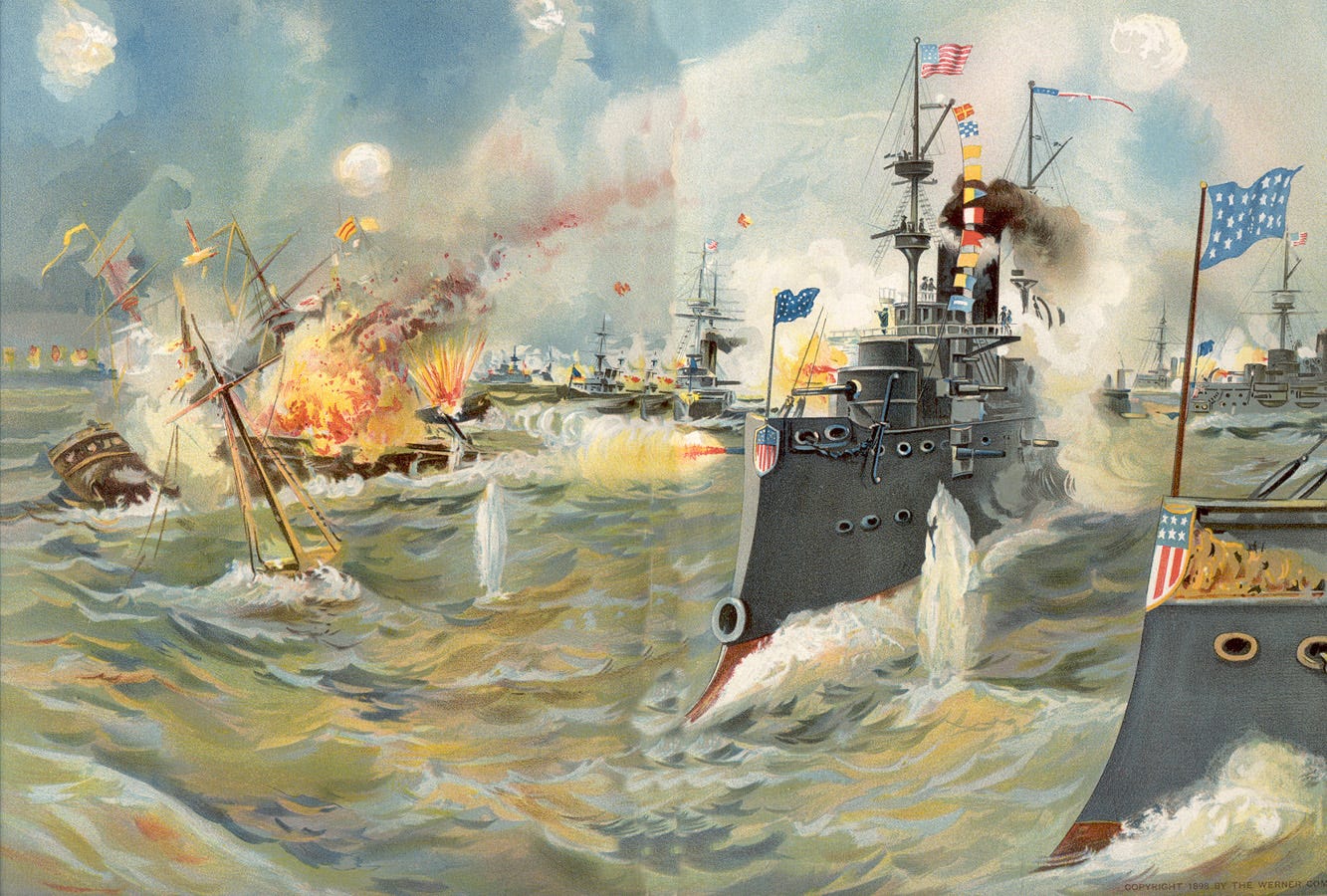

You can see from the map that to attack Manila Bay took some guts. The American squadron had to exercise skillful navigation in order to maneuver inside of the bay whilst also avoiding minefields. They timed their approach at night, to avoid being spotted by the many Spanish forts. Led by the cruiser Olympia, the attack began at 5:15 a.m. The Americans had largely achieved surprise, despite being spotted by the forts thanks to Revenue Cutter McCulloch emitting sparks from its smokestack. The Spanish forts and fleet were less than effectual in terms of gunnery. The Americans were under fire for a full twenty minutes before they began returning fire. The Americans performed a disciplined figure-eight maneuver, staying in formation. The Spanish ships which could heave anchor and get underway were not able to get into a formation and mount a coordinated attack. Thus, they blocked each other’s fields of fire as they attempted to maneuver.

The action was broken off mid-morning due to Dewey’s concern for ammunition. Once it became clear that there was enough ammo to continue, he began the attack again after a meal, with this second portion of the battle beginning at 11:16 a.m. After this latest onslaught, the Spanish put up the white flag. It was over. Supposedly, only one man on the American side was killed, and not even by enemy fire. He died of a heart attack.

This victory is significant because it created the American sphere of influence in the South China Sea, which still exists to this day. It is a uniquely American victory in an incredibly aesthetic and European age. Hail Columbia.

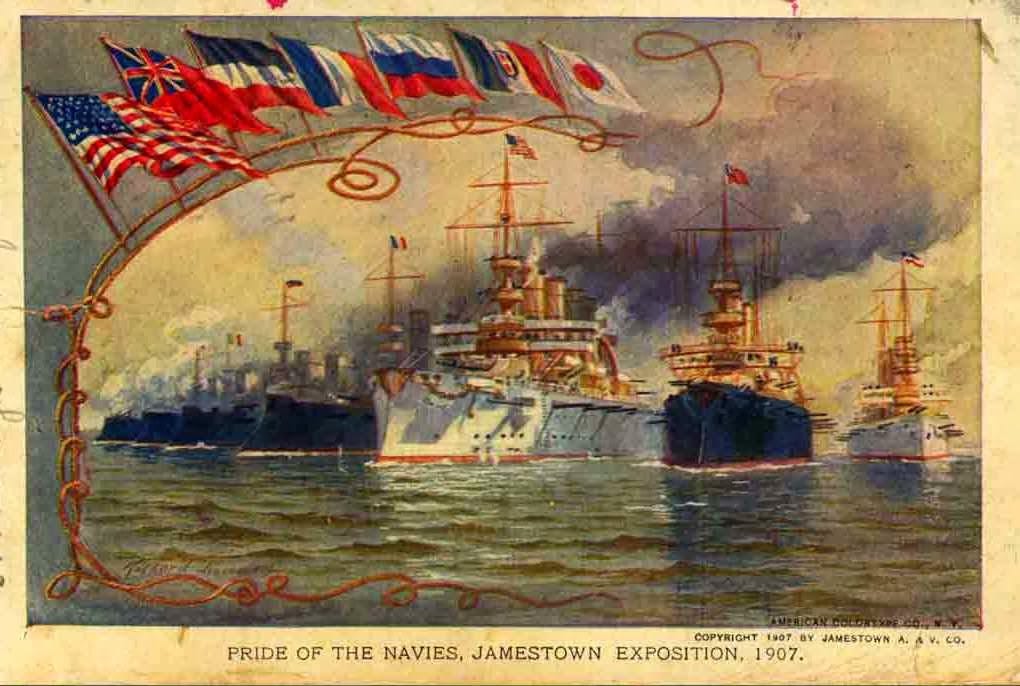

Regarding the point about Revisionism and conflict between Europeans. The postcard included includes the USA, Britain, Russia, France, Italy, Japan, one or two others, but not Spain. This often seems to be the case. In the 19thC nobody cared about Spain. I suppose they were rather diplomatically isolated (not involved in the Great War), waning in power, and beset by revolution and upheaval. The Spanish Empire was for game for European nations to pick apart. It was also populated by brown people