By guest contributor Charles Carroll.

Discovering a continent is no ordinary feat. Yet, it is something so vastly under-appreciated, if not scorned, by the ingrates of today. We should probably get it through our heads first and foremost just how era-defining it was for the New World to have been discovered. When our schools tried to teach us the approved narrative, it may have even seemed boring, if not also a matter of embarrassment and shame; but the reality is that the real history of the New World’s discovery was one of the greatest adventures Western Man has ever set out on. I would go out on a limb and say that it was only ever truly bested by our adventures to the Moon.

The only other hindrance to truly appreciating this era in Western history is our bias toward our comfortable and modern lifestyles. A fact often lost on us is that merely having something as simple as air-conditioning has elevated our living standards beyond those of the kings and queens of Europe during the Age of Discovery. Okay, I am not entirely sure how accurate that judgment would be, but you get the point. Life in Europe during that time was hard enough, and Europe had already long been settled and built! Imagine how much more difficult it would be, then, to step out of a compact, wooden boat onto an unknown landmass with the intention of building and replicating European civilization from scratch.

The land we are graciously allowed to call our home today had to be subdued by our ancestors. In our current comfort, we must remember that it wasn’t always like this. For the newly arrived European, the Americas were a vast and unexplored landmass. No one knew the boundaries, and all freely speculated about its extent and what lay in it. Treachery and danger lay hidden in every tree and behind every bush. There were no maps with which to navigate — those would eventually have to be made. Whatever tools you brought along were all you had for the road. Everything would have to be built here, or else you would be forced to wait for unbearably long times for needed replenishments from the Old World. The most harrowing of all were the inhabitants. It must have been nerve-racking for the Europeans to be by themselves in such small parties compared to the large tribes of the Indian peoples. Factor in as well the ignorance on the part of the Europeans as to how many Indians they would ultimately have to deal with, and the stakes only get more dire. Would they be friend or foe? As we know from history, at times they would be peaceful and gladly extend a helping hand. Of course, we also know that at the worst of times, they would be just as vicious in combat as the Europeans.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom, misery and mayhem, however. There must’ve been something attractive for the Europeans in order for them to stake their lives in settling this newly found land. One of the greatest contributing factors towards European settlement, and something I don’t see or hear even discussed, was European imagination. Here is a new land, brimming with potential! A land that might be teeming with gold and silver. The Spanish discovery and conquering of the Aztec peoples confirmed many of their hopes of vast wealth ripe for the taking. Here was a continent that shouldn’t be here — let alone a vastly wealthy and barbaric civilization — that attracted all sorts of men hoping to make a name for themselves in the annals of history.

The New World tempted the Spaniards as much as Troy and her vast wealth tempted the Greeks. Yet, in both cases we see the daring adventurers become entrapped into horrific quagmires. Much like the eponymous hero of Homer’s great epic The Odyssey, our Spanish hero found himself in someone else’s adventure, only for fate to make it his own story. Similar to Odysseus, this man would depart from his home country in search of glory, only to labor ultimately for a chance to return home, which might take a decade. Homer’s Odyssey saw the gods use their powers over nature to persecute Odysseus and hinder his return home, while in the New World expedition that concerns us today, one would be forgiven for reckoning that the gods just as well conspired to persecute this Spanish man. One by one, the Greeks fell, until all that was left was just Odysseus. In a similar vein, the Spaniards, through a series of unfortunate events, were whittled down to only four survivors.

Pánfilo de Narváez

The namesake of this expedition, Pánfilo de Narváez (1470–1528), is not our Odysseus here — we shall introduce him soon enough — but first we should introduce Narváez. Narváez was the expedition leader who was made governor of the then-unexplored territory stretching from the Cape of Florida to the Rio Grande. King Charles I of Spain appointed the conquistador as governor in order to subdue and conquer this territory for the Spanish Crown and also in order to bring Christ to the Indians who resided there. As part of compensation, Narváez would be entitled to profits from this territory after the Crown received its share. If Cortés’s experience was representative of anything, surely Narváez would strike just as big and stumble upon hordes of gold and silver. This was the siren-like appeal behind exploring the New World for the Spanish, the possibility of untold riches. Unfortunately, as we shall see later on, Narváez will not make it home.

Narváez is an interesting character even outside his appearance in the doomed expedition. His early ventures in the New World were without a doubt foreshadowing of the bad things to come. In 1520, the Spanish governor of Cuba, Diego Velásquez, ordered Narváez to lead a thousand-man crew to capture and arrest Cortés while Cortés was in the middle of conquering the Aztecs. The funny thing about Cortés’s expedition to Mexico is that it was technically illegal. You see, his permission to take a crew to Mexico was revoked by the Crown, but Cortés decided to ignore it and go ahead with it anyway. This so infuriated the Cuban governor that he commissioned Narváez to lead that thousand-man force to capture him. To sum it up quickly: Cortés convinced the men under Narváez to join him, Narváez lost an eye fighting Cortés and his men, and Narváez would be made a prisoner under Cortés for about two to three and a half years. Not the best welcome to the New World.

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca

The real hero of this journey was the second-in-command to Narváez, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (1490–1559), who coincidentally had the most stereotypically Spanish-sounding name. He’s the man to root for, the Odysseus of the story who was fated to return home. Cabeza de Vaca translates to “cow’s head,” but the significance of that surname remains unknown. He was primarily an adventurer and then became a historian later, and for that we are grateful. What we know of this voyage and its aftermath was chronicled in great detail by Cabeza de Vaca himself in his Relación (Account) published in 1542. During this voyage, he was both the treasurer and master-at-arms. As master-at-arms, he had the authority to arrest, and as treasurer, he was given the duties of sending gold back to the Spanish Crown and ensuring that the men were paid.

Hispaniola and Cuba

The group set sail from Spain towards Santo Domingo in Hispaniola (present-day Dominican Republic and Haiti) in June 1527. Along the way from Spain to Hispaniola, the crew had a brief resupplying layover in the Canary Islands, just off the coast of present-day Morocco. Come September, as they approached the shores of Hispaniola, they would receive premonitions of things to come. You see, another expedition had ended in a terrible disaster just the previous year, and the men under Narváez heard all about it. In 1526, that other expedition had been sent to found a colony to be named San Miguel de Gualdape in present-day Georgia. That expedition, led by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, would sadly only last three months, during which three-fourths of the men were killed off. Narváez’s men were not so thrilled at this news, and 140 of them decided that it was an appropriate time to desert. Narváez had landed in Hispaniola in hopes of resupplying and better preparing his men for the journey ahead, but now he had lost a decent chunk of his men.

They next ventured to Cuba to remedy this large desertion. In Cuba, they picked up more men and some horses, and even purchased another ship for their use. And this is when they received their next premonition. That area is known for hurricanes, and Narváez would be in luck to experience one! In this storm, Narváez lost 60 men and 2 ships. With his crew spooked, he would have to wait the winter out. Luckily, Narváez picked up another ship whose captain, Miruelo, claimed to have sailed the region they were sent to explore. By February 1528, Narváez decided that it was high time for some more sailing. Departing Cuba, Narváez now had 6 ships, 480 men, and 80 horses with which to explore Florida. For whatever reason, ten of Narváez’s men had decided to bring their wives on this highly dangerous expedition.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus became the target of Poseidon’s wrath after Odysseus blinded Polyphemus, Poseidon’s cyclops son. Well, someone in this crew must have ticked off the sea god in a similar way, because the Spaniards would be subjected to the mercy of the sea again. Two days after departing from southern Cuba, the ships ran aground on a shoal on which the expedition would be stuck for two to three weeks until the sea level raised them. Narváez had hoped that they could stop in northern Cuba to pick up another ship, but the storms and winds were too great to sail against, and they would be pushed out into the Gulf of Mexico. After a month of fruitlessly battling Poseidon’s unhinged anger, Narváez decided that he would no longer tolerate any more delays. He finally set sail towards Florida without a new ship.

Tampa Bay

After 48 days at sea since departing from Cuba, the expedition spotted land near the western portion of Tampa Bay. Unfortunately, 38 horses perished along the way on the seven-week journey just to get to Florida. Miruelo had guided this expedition to find a harbor that he claimed to have been familiar with. Instead, he led them to an unfamiliar spot which was likely 15 miles away from the intended destination. It was here that Miruelo got lucky, because the expedition was split into two components. Miruelo would be sent leading part of the expedition on the seas to find the port where they had initially wanted to land, while Narváez would lead the men on land.

If Miruelo couldn’t find the harbor, then he was to sail back to Cuba and pick up that ship awaiting them with some extra supplies. Miruelo could not find the harbor and was forced to sail back to Cuba as ordered. Unfortunately for Narváez’s men, when Miruelo returned to the Floridian coast with all the needed supplies and even a brand-new ship, he could not find the land contingent led by Narváez. For over a year, Miruelo and his men sailed up and down the coast of Florida trying to find their lost comrades to no avail, eventually deciding that it was time to call it quits and head back to Cuba. With that, Miruelo is out of the picture, stranding Narváez and his men on an unknown continent.

Finding Apalachee

If it sounds like a bad idea to separate from your ships in order to find a harbor of whose location and even existence you were uncertain, then you’re not alone. Our story’s Odysseus, Cabeza de Vaca, made sure to voice his concerns, only to be overruled by the rash Narváez and most of the other leadership. When the ships departed, the land contingent decided to set out and find the village of Apalachee (or Apalache) that was rumored to abound in gold. The party was led by an Indian they found, who most likely was playing a trick on the Spaniards so that the Indian’s people could avoid a fate similar to that of the people of Central America. For seven weeks they traveled, a party of 300 men and 40 horses, in hopes of finding the mythical city of gold. And the amazing thing is that they did find Apalachee, sort of. It turned out that Apalachee was a small village of around 40 huts, and the only gold they had was actually corn. This continent so far wasn’t panning out like it was supposed to.

It was at this point that they knew that they were in trouble. After not sighting Miruelo for some time, they came to the realization that they were stranded and would have to find their way home. It was also at this point that the Indians they started to encounter were of the aggressive variety and quite adept at archery. Seeing the situation deteriorate, with illness and arrows claiming the lives of the Spanish men, it was high time they built some boats to sail away from Florida to somewhere controlled by Spain.

Mind you, these were soldiers, not engineers or craftsmen, with only just one carpenter, so they were forced to make the crudest of boats. To do so, the boats would have to be made out of every scrap of plant and trees they could accumulate. They resorted to crafting their own bellows from deer skin and hollow wood so that they could melt their stirrups to make saws and axes for cutting down trees. The men had to sacrifice their own shirts if their boats were to have sails and any hope of navigating their way out of Florida. The horses didn’t fare well in this situation, either. Every third day, a horse would have to be eaten due to the lack of food amongst the men, and the horses’ hides were used to store freshwater. The sacrifices of those poor horses would not go unappreciated: Apalachee Bay, the area from which the doomed men would depart, came to be known as the “Bay of Horses.”

Obviously, these boats were hardly close to seaworthy, but it was the best they could do. Amongst 251 men, they had 5 boats built to accommodate their travels. It wasn’t quite a good sign either that, upon entering the boats, they found it was only barely six inches above the seawater. If they wanted any chance at making it home alive, then they would have to hug the shore as they sailed onwards. They had hoped to sail towards the Spanish settlement of Pánuco, but unbeknownst to them it was actually 1,200 miles away from them in the present-day Mexican state of Veracruz. Their vast underestimation is somewhat understandable, given that there were no maps, but this mistake would cost them their lives. Cuba, meanwhile, was only 400 miles away.

Setting Sail

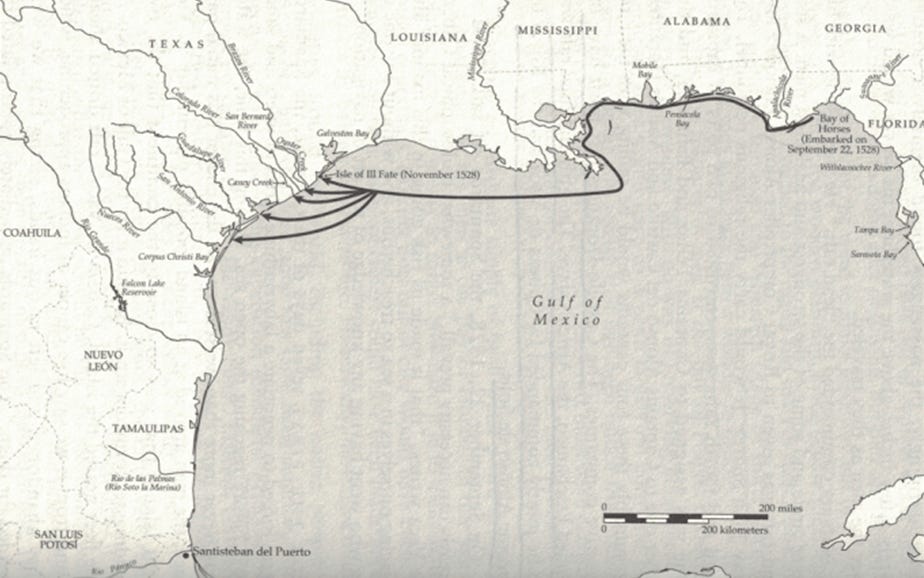

Towards the end of September 1528, it was time to put their boats to the test. For a month, it was actually smooth sailing and maybe, just maybe, their luck had improved. But as you can tell from the unfortunate occurrences that had so far befallen them, it wasn’t to last. Soon, they approached the mouth of the mighty Mississippi River, becoming the first Europeans to lay eyes on that majestic river of which Mark Twain would write so fondly centuries later. However, the river was not a welcoming host, venting its frustration and anger towards the Spaniards just as the cyclops had attempted to kill the Greeks under Odysseus’s command. The current of the river spewing into the Gulf alongside and some strong winds scattered the boats into the Gulf, leaving each ship to fend for itself. After a few long, agonizing days, each boat made landfall at various spots along the Texas coast.

Cabeza de Vaca landed on an island in close proximity to another boat, but he was unaware of this until they came across a friendly Indian group who provided food and other aid. When Cabeza de Vaca noticed a Spanish trinket in the hands of an Indian, he would quickly find out that another crew of Spaniards had landed nearby, and the two groups were reunited.

Narváez’s crew consisted of the healthiest men, and they likely were able to reach the shores of Louisiana intact for some time. They eventually came upon another boat that was wrecked near Follet’s Island. Her crew had decided that it would be better to walk than to sail. Those two groups eventually reunited as well and would attempt to enjoy a nice, quiet evening together. Narváez, however, was sick along with two other men, and they decided to stay aboard the boat with neither water nor any supplies. At night, strong winds picked up, and the boat carrying the three sick men was never to be seen again. The sea gods finally claimed their much-sought-after prize: the blood of Narváez. The final boat was left all alone, and the others had lost sight of it. From what we know, wherever they may have landed, they were quickly massacred by a group of Indians.

Winter of 1528–1529

With winter quickly approaching in late 1528, it was decided by each camp to settle down to ride out whatever nature would throw at them next. By this point, there were 160 men left out of the initial 251. At the end of the Texan winter of 1529, however, there were only 18 men left. Starvation and exposure finished men off one by one. In one camp, only one man by the name of Esquivel would survive by resorting to cannibalism. An Indian group discovered him feeding off of a fellow soldier’s corpse, and they took him as prisoner.

As for Cabeza de Vaca’s camp, four men were sent off in hopes of trekking it to Pánuco for help. Only one man, Figueroa, would survive, and he was captured as well by another group of Indians. Cabeza de Vaca’s group found some initial luck, being hosted by a friendly Indian group. However, as the winter worsened and food became ever more scarce, the Natives became increasingly hostile towards the Spaniards and even demanded that the Spaniards start chipping in. The Indians demanded that the Spaniards start healing the sick Indians, despite having no medical knowledge whatsoever. The Spaniards were obviously reluctant in the likely chance that their medical interventions failed, but when food started to be withheld, then they suddenly became doctors. Their treatment plan was to make the Sign of the Cross over the infirm Indians and to pray out loud for them. The Indians were satisfied and began sharing once again. By the end of that rough winter, 13 men assembled, and they started to make their way towards Pánuco on foot in April 1529.

Cabeza de Vaca’s Odyssey Continues

Along the way, they even ran into Figueroa, who gladly joined their group. Three men were left behind with the host Indians, including Cabeza de Vaca, who was too ill to travel. Among the men left behind, one died from his illness while Cabeza de Vaca and another named Oviedo recovered. Oviedo, however, was reluctant to leave the island, as he could not swim, so Cabeza de Vaca was forced to leave the island alone. Cabeza de Vaca then traveled village to village, becoming a trader of items that the Indians valued, such as dyes, seashells, and other nicknacks. Once a year, he would return to that island to plead with Figueroa to leave with him. It would be several years until Figuero finally decided, in 1533, that it was time to flee the island with Cabeza de Vaca.

The duo then encountered some Indians who informed them that they had run into six other Spaniards. The news was not all welcome, however, as three of them were killed by the Indians while the other three were enslaved — but there were at least three others alive! Oviedo lost heart and absconded with the Indian group they had just encountered, never to be heard from again. Eventually, the Indians led Cabeza de Vaca to his three friends whom he joined in slavery. It took until about a year later, in September 1534, that the four could escape from the bonds of slavery.

Not to bore you with more details, but these four men moved agonizingly slowly across Texas, where they did happen to have a string of lucky encounters with many friendly Indians. The important thing to consider here is that they were finally moving and making progress towards safety. After months of traveling across the interior of Texas, they approached the Gulf of California, where they finally hit their biggest break: an Indian was found wearing a Spanish buckle, meaning that the Spanish were nearby. They eventually found a Spanish outpost by the name of Culiacán, in the present-day Mexican state of Sinaloa, in the spring or early summer of 1536. They had left Spain in 1527, and would be in exile for nearly a decade before returning to the safety of their kin. The New World might have been a treasure chest for some, but as we see here, it could also be the ruin and source of misery for many.

Sources

“Narváez, Pánfilo De,” Texas State Historical Association, [1995] 2020.

On Cortés’s exploits: “Spanish Colonization: Conquest of Mexico,” OERcommons.org.

On the attempted arrest of Cortés: “The Narváez Expedition,” American Historical Association.

“Cabeza de Vaca, Álvar Núñez,” Texas State Historical Association, [1952] 2022.

Rolena Adorno and Patrick Pautz, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: His Account, His Life, and the Expedition of Panfilo de Narváez, 3 Vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

“1527 Detail, Narváez Expedition Leaves,” America’s Best History.

“The Misadventures of Pánfilo de Narváez and Nuñez de Cabeza de Vaca,” Exploring Florida, Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida, 2002.

“The Narváez Expedition,” TexasCounties.net.

Thanks once again for allowing me to write!

This is great. I think celebrating our adventurers and the entire high trust society that permitted and supported these voyages is a great endeavor. I took a shot at Columbus last year but I bet you can do better. One thing I learned when writing this up is that Columbus a) discovered the Panama canal and had the vision for it b) he charted the wind and water currents of the Atlantic and of the Caribbean as well as mapping out the tides and currents in the Caribbean in addition to the coast. I also learned that a huge motivating factor for sea exploration was the Ottoman sack of Constantinople which closed the land based trade routes with the east. (https://periheliuslux.substack.com/p/celebrate-columbus-day)

One bone to pick on Odysseus. This is very important to us today. Odysseus tricked the cyclops into not being rescued by a fellow cyclops by telling the the cyclops his name was Nobody. When his buddy passed, the cyclops couldn't be rescued and thus Odysseus and his crew eaten, because when asked, "Who is there?", the cyclops replied, "Nobody."

This is the fatal mistake of Odysseus' conceit. Once escaped and with his crew on the ocean in anger and a moment of vanity he screamed at the Cyclops, I am Odysseus and taunted him. Thus the Cyclops complained to his father Poseidon and it was only because of Odysseus vanity and fool hardiness in his escape that Poseidon knew who harmed his son and thus who to torment on the seas. If Odysseus had not taunted in a hot-headed moment and just quietly made his escape he would have had a much easier journey home.

This is wisdom that will serve us at some victory or set of victories in the future. Great post. Thank you for doing this. I would love a whole series on our great navigators.