The New York Yankees & The American Century

If Ovid were American, he’d write about Baseball.

By guest contributor T.R. Hudson.

Baseball is the American pastime, and the New York Yankees are America. There have been 120 World Series between the American League and the National League, the two main “conferences” of teams in the United States. Of those 120 World Series, the Yankees have won 27 and participated in 41. The team with the most wins after the Yankees are the St. Louis Cardinals with 11. The team with the most appearances after the Yankees are the Dodgers, originally from Brooklyn before moving to Los Angeles.

You can’t get more American than a Yankee. I’m sorry to report, my Southern brothers, but around the world, Americans are called Yankees. South of the border, no matter if you’re from Biloxi or the Tidewater, you are a “Yanqui.” Every doughboy and GI who went to Europe was a “Yank,” even if he was from Austin or Charleston. In some alternate reality, perhaps we’re known as Dixies or Rebs, but we live in this reality. Around the world, people wear Yankees caps without knowing the sport the team plays, only knowing that it is American and, therefore, cool.

The Yankees, like the United States, are the most hated organization in the MLB. When you’re on top, you’ve no choice but to look down on the rest of the world. I perused the Internet to figure out what Yankees fans thought of all the hate they and their team receive from baseball fans, and I found this choice quote on the Yankees subreddit:

Our historical rival are the Boston Red Sox.

Our rivals of the past decade are the Houston Astros.

Our current rival is our incompetent ownership & front office.

The Blue Jays are just a team in our division.

One could easily replace Boston with Russia, Houston with China, the ownership with our government, and the Blue Jays with Canada and not miss a beat. The 20th-century rivalry of the Red Sox and Yankees could easily fill as many volumes as the Cold War between the USSR and USA. Both red menaces came up short against the Yanks, getting their licks in here and there but never quite putting it together enough to win it all. The 21st century has seen both Russia and the Red Sox ascendant, though I will put an end to the analogy here before it gets too ridiculous.

The last 120 years of American history have seen the rise of a continental power to global power, global power to superpower, and we are now witnessing the fall of a superpower back down to Earth and possibly further still. Like the country it represents, the New York Yankees, too, have followed the path that destiny has laid out for the United States, and this rise and fall can be mapped out on the play of a few players who best represent the team and the nation.

Before the Yankees

Much like America before the Constitution, there is a long, storied life of baseball before the Yankees that few outside the devoted historian pay much mind to. Groups of independent clubs would eventually band together to form the two leagues we associate with the Major Leagues, just as the country would have to come together and rip itself in two in a bloody Civil War that changed how America saw itself. Pre-Yankee baseball was a small, growing sport that grew to national heights and, soon, international acclaim. America, too, had entered the 20th century ready for a larger place on the world stage, establishing itself as an economic powerhouse and global empire after its victory in the Spanish-American War. From 1900 to about 1919, baseball established itself as the national pastime in what would later be known as the “Dead-Ball Era.” In 1912, the Yankees were officially named, though they were known for 12 years prior as The Highlanders and The Americans. This era was defined by defensive play, pitching chicanery in the form of ball manipulation. There was only ever one ball used, and the pitcher could do anything to it. Some balls were described as black from all the chew tobacco spit that stained them. This era was dominated by hitters like Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, Joe Jackson, and Nap Lajoie as well as pitchers like “Smoky Joe” Wood, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, and Cy Young. One name loomed large over the Dead-Ball Era, the father of the modern game: John McGraw.

McGraw managed the New York Giants from 1902 to 1932, appearing in nine World Series (there was no 1904 World Series), winning three of them. He is one of the winningest managers in the history of the game, tying his disciple Casey Stengel for most Pennant wins with 10, and is the second-longest-tenured† manager in Major League history. His tenure was marked by an intense desire to win, getting the best out of his players, while also exacting dictatorial control over his roster and players’ behavior. McGraw innovated the game with the advent of “relief pitchers” who substituted the starter on the mound. Before Billy Beane and “Moneyball,” McGraw built his teams to play “inside baseball,” a strategy of getting on base and thereby scoring runs. John McGraw was the example that later Yankees manager Casey Stengel learned from. John McGraw’s early 1920s teams were the best he’d ever assembled, and he said as much. He probably would have won more World Series titles with that team. But Babe Ruth happened.

The Babe, Big Baseball, and Big America

Imagine the cavalry as it looked at the first machine gun. The cavalry officer, inheritor of the prestige and noblesse of the medieval knight, would look at the big industrial eyesore with scorn, unable to imagine a use for such a crude device on the field of battle. He’d think it was too slow to move, so it couldn’t be on the front lines, its range of fire too short, so it couldn’t be artillery, and it would easily be captured by the horseback soldiers who’d defined European warfare since Alexander the Great. On the first charge, if the cavalry officer was lucky, he’d survive the wall of lead fired in his direction and would spend the rest of the war carrying ammunition and supplies from one place to another or slum it in the trenches with the infantry; either way, his way of doing things was dead. This is basically what happened when Babe Ruth joined the Yankees.

By the time Babe Ruth was sold to the Yankees, he was already one of the best players in the league. Had he remained a pitcher, he probably could have made the Hall of Fame on the strength of his arm alone. In 1916, he pitched nine shutouts, and though Ruth wanted to play every day at a different position, it was a gamble that most managers would not want to risk. But the gamble paid off in a big way, and Babe Ruth’s power in the batter’s box introduced a new way to play the game. John McGraw’s Giants faced off against the Yankees in four consecutive World Series, splitting the difference. McGraw’s old way of playing the game came face to face with Ruth’s new way, which was “get guys on base so Babe can score them with a home run.” Their first two meetings, McGraw came away with the wins, having to assemble “the best team I’ve ever seen” to beat Babe Ruth, who did not even get to play most of the games in these two Series due to injury. By 1923, playing in their own stadium, the Yankees were able to overcome the grand designs and system of McGraw with the raw power and ability of Babe Ruth.

Babe Ruth did not score the first home run. Home runs had been part of the game since the beginning of the sport in the 1860s. However, Babe Ruth was the first player who could consistently hit home runs. In 1919, Ruth broke the single-season home run record with 29. He would break that record again the next season, his first with the Yankees, with 54. He’d do it again the next season with 59. Ruth would later break his own record again in 1927, setting the league record that would later be topped by New York Yankee Roger Maris in 1961. (Ruth completed this feat in 154 games, but Maris did it in fewer at-bats, so…)

The Babe was the first baseball superstar and represented America’s growing wealth and status, even representing its excesses. America loved Babe Ruth, and Babe Ruth loved America. As America was victorious in the First World War and showing itself as a major world power, even a leader on the world stage, Babe Ruth represented America’s growing need for more, to the point of excess. Food, drink, women — enough was never enough for Ruth or the generation of the Roaring Twenties. Even when Black Thursday hit the stock market and many fortunes were wiped out, followed by a decade of Depression, America never lost its taste for the finer things in life.

Building great skyscrapers, winning wars across the globe, building the empire, and going to the Moon — all these accomplishments were born out of America’s drive to be exceptional, and while Babe Ruth was not the first man to walk on the Moon, nor was he around when the first settlers headed West to accomplish that first great American journey, Manifest Destiny, he was a man of his time, for his time. Ruth, like the other men on this list, and like most baseball stars worth remembering, is like a Greek Hero in his representation of his people. He was the first major athlete that everyone knew, thanks to the radio, but also because of his athletic prowess and humble beginnings. Anyone could be Babe Ruth because he was just any other guy. When John F. Kennedy declared that America would go to the Moon, one could swear he was invoking Babe Ruth, calling his shot, pointing out into the great unknown, and, best of all, pulling it off.

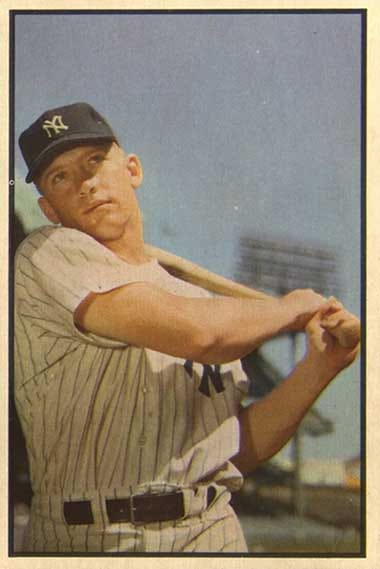

Babe Ruth was the greatest ballplayer that ever lived. He was this way because he was a New York Yankee. But it was also Babe Ruth who made the Yankees what they are. Yankee Stadium is “The House That Ruth Built.” Before his tenure on the team, the Yankees shared a stadium with that Remus of New York, the Giants. After both the Giants and Dodgers left, the Yankees have remained the sole kings of the Empire State (the Mets and their two World Series Championships and four appearances notwithstanding). Ever since Ruth, the Yankees have had a standard for their players: they needed to be Homeric in their play and personas. Flaws were airbrushed away (especially in the case of Mickey Mantle — more on him in a bit), and stories were embellished about them and, better yet, believed (e.g., some people think Babe Ruth saved Johnny Sylvester’s life by hitting a home run). If Babe Ruth had played for the Detroit Tigers or the Cincinnati Reds or remained forever with the Boston Red Sox, he would have done just as well on the field and maybe better, not having the great distractions of New York to indulge himself on. But he wouldn’t have been Babe Ruth, the legend we still remember today.

Babe Ruth means victory. It means that every at-bat could send the ball out of the field and even out of the park and into someone’s house. Babe Ruth had seven World Series Championships, the MVP Award, and the All Star of All Stars. He was in the first class of Hall of Famers four years after he’d retired. Even 100 years after he played, Babe’s face is still one of the most recognizable in America sports. Hell, it’s because of Babe Ruth and his international tour that Japan adopted our pastime and now lays claim to the best player in the league, Shohei Ohtani, whose ability to hit and pitch at an elite level has drawn comparisons to Ruth himself. The man was a machine gun against a cavalry charge, and the terrible beatdown he put others through changed the way the sport was played forever, making baseball the biggest sport in America. Babe Ruth embodied the attitude of a country that wanted to do great, big things, coupled with the will and ability to do them.

A Brief, Bright Flash

It feels like sacrilege to skip over Lou Gehrig’s career with the Yankees. Lou Gehrig, The Iron Horse, The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth, The Pride of the Yankees. But, while Lou was all these things and more, his legacy, like those of most tragic heroes, is the terrible ordeal that leads to his untimely death. Lou Gehrig died of ALS in 1941, and it will forever be known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He played 15 ½ seasons in the Majors, retiring as the disease took its toll on him. His 2,130-game starting streak was thought of as one of baseball’s untouchable records (later broken by Cal Ripken, Jr.). It’s one of those great ironies: the man who played through grave injury, every game, sometimes barely limping into the batter’s box to play that day, finally being brought down to Earth by illness; what the Greeks would prescribe as a punishment from Mt. Olympus for Gehrig daring to be immortal like the gods were immortal. Lou Gehrig played all of his baseball in and around New York. He was only ever a New York Yankee in the Majors. It’s such a shame that he’s remembered for the disease that took him so young.

Bedding Marilyn Monroe and Playing Ball to Win the War

I think there was one man that actually loved Marilyn Monroe, and that was Joe DiMaggio. It seems like every American worth looking up to (and Arthur Miller) had a liaison with Ms. Monroe in her “Candle in the Wind” life, but it was Joltin’ Joe who loved her. When she died, it was DiMaggio who arranged her funeral, keeping Hollywood and the Kennedys away from the service. He sent roses three times per week, every week, for 20 years to her crypt. In a time where it was undignified for a man to express emotion in public, DiMaggio cried when his divorce to Monroe was finalized.

I started out this part of the essay on DiMaggio’s life after baseball because he’s really the first Yankee to have an “after baseball” life. Babe Ruth, after retirement, was a celebrity, but he was professional baseball. For the rest of his life, he tried to be around the game in some capacity. He was heartbroken never to get a proper manager’s position with a big-league club. Lou Gehrig died in agony after his career was over. Joe DiMaggio lived a full life, dying at age 84, his reported last words being: “I’ll finally get to see Marilyn.”

The Yankee Clipper helped to make Italians American. Even when his parents were considered enemy aliens during the war, DiMaggio joined the Army and, in true Italian-American fashion, was given a no-show job coaching soldiers on physical fitness while playing baseball to entertain the troops. Ted Williams was a better ballplayer than DiMaggio. He was a bona fide fighter pilot and later hero in the Korean War, and though he resented the government for stealing his prime from him, never said so out loud. That said, Teddy Ballgame did not have “it.” Joey D did more for Italian assimilation than any politician or policy, and maybe even more than that other great wop, Frank Sinatra. If assimilation into America is possible, it is in the model of Joe DiMaggio.

Assimilation is a dirty word these days in America. Those on the Left see it as oppression and cultural chauvinism to be avoided, instead opting for a multicultural “melting pot” of ideals centered on the promise of economic stability and prosperity. Without those, we’re living in Samuel Huntington’s world (we always have been). The Right, meanwhile, seeing multiculturalism as impossible, reckons that there can be no assimilation. In fact, many of America’s premier novelists say as much. Philip Roth in American Pastoral, for instance, shows how an American Jew who gives up his “Jewishness” to buy into America achieves neither and, instead, exists in this strange middle ground with no one to turn to. The Godfather goes into this as well, in the beginning with the undertaker Bonasera, who first tries to use the American justice system to right wrongs done against himself and his family, but must fall back to Don Corleone to get real justice. Assimilation means the destruction of your previous identity in favor of the identity of your new home. It’s the deal you make. Nothing’s free.

Anyway, the Daeg, as DiMaggio was known by his teammates, was used to being taken care of. Wherever he went, people wanted to be around him and get him things. Gangsters looked up to him and wouldn’t even dream of asking him to throw a game. Joe was so fast and so good at hitting and so good for Italians in the country, gamblers couldn’t ask him to take one for the team. It would be like clipping an eagle’s wings or shooting a unicorn.

When America saw Joe D, they did not see the typical Italian, whose greasy hair and greasy skin and Roman Catholic ways were a nightmare for Anglo sensibilities and society. They saw a laconic, almost aloof man, who went about his business in the restrained, dignified way that your typical WASP could find kinship with. Where the standard view of Italians had been figures of organized crime and ethnic strife in cities like New York and Chicago, Joe broke the mold. His marriages to both Dorothy Arnold and Marilyn Monroe, both beauties and representatives of American culture, were another bit of stitching that brought Italians into the American identity.

DiMaggio is probably best known in baseball for his 56-game hit streak. In a league where you are considered good if you can get a hit 1 out of every 3 at-bats, DiMaggio got a hit in 56 straight games. Where many wondered if Lou Gehrig’s game streak would be broken, no one wonders if DiMaggio’s record will ever be broken. It won’t. Statistically, it might be the most unlikely event in the history of the sport. This feat is made more impressive when understood as the second time DiMaggio had done it in his professional career: he’d previously done a 62-game hit streak in the 1930s with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.

America, after the war, was on top. They boasted the highest living standards, greatest economy, and a new medium for mass media — the television. Joe DiMaggio, normally a face-for-radio type, was already famous across the U.S. as being the best ballplayer on the best team, but with televisions making their way into American homes, the most popular sportsman in America was chasing names like Joe Dempsey and Babe Ruth in the American consciousness.

DiMaggio knew this, too. Whatever heroics he put out in the field, he always expected to get his share. “To wet his beak,” to borrow from The Godfather Part II. Baseball was his career. He had no great love for the game. Even as a kid, he only played with his friends when everyone could gather enough pocket change to make it worth Joe’s while. He’d attempt to sit out if he didn’t like his contract. He even got nightclubs to pay him appearance fees whenever he hit the town. Later in life, he was the face of Mr. Coffee. When Mickey Mantle died in 1995, commemorative balls were created to celebrate the Mick, and those were sold for $10 per ball. The Yankees also created Mickey Mantle Day. Joe didn’t like that, demanding a Joe DiMaggio Day and his own custom ball, every single one of which he signed, netting him a big payday. Such balls go for about $1,300 today.

That, above everything else, was the Clipper’s dark side. He needed to be loved. He needed to be taken care of. His marriage to Monroe didn’t work out, in large part because he was neurotic and took that out on her and beat her and drank too much and beat her more. He resented Mickey Mantle, who was the golden boy behind DiMaggio, waiting for Daeg to retire and fill his shoes, as the Yankees center fielder, as the team’s best player, and also as the most recognizable name in sports. The 1951 World Series was both DiMaggio’s swan song as well as Mantle’s coming out party. The tragedy of that day, with Mantle’s injury on the field and DiMaggio’s culpability in the events — Mantle never said so out loud, but implied that DiMaggio was at fault, while DiMaggio, later in life, tried to smooth over his role in the injury, saying that he’d told Mickey he could snag the fly, which, knowing DiMaggio, definitely didn’t happen — was that DiMaggio’s legacy was blemished, and Mantle, as great as he became, was never going to be as good as he could have been.

The Mick and Boomer Heroism

When I came up with the idea for this piece, it was supposed to be an essay about Mickey Mantle. The Mick was America in the 1950s and ’60s. There are marketing men who wish that they could find another name like Mickey Mantle. It rolls off the tongue and inspires imagery of flags and fighter jets and road trips and baseball. He was our Achilles, to go back to the analogy of Greek heroes. Where Achilles had his heel, Mickey had his knee. In the 1951 World Series, Mickey Mantle was a rookie and was the next big thing in baseball. Depending on your version of the story, either a) Mantle had been told he could grab a fly ball by center fielder Joe DiMaggio or b) Mantle, who’d not learned the proper etiquette of the outfield, was trying to shag a fly that the Clipper had also claimed. Whatever the story, Mickey stopped his dead sprint to allow DiMaggio to get the ball and tripped over a hidden drain pipe in Yankee Stadium. Mantle’s injury was never properly diagnosed, but it is now believed that he tore his ACL on that play. He would play in agony on that torn knee for 16 more seasons.

Mantle came from the American Heartland, a little nowhere mining town called Commerce, Oklahoma, the kind of town Thornton Wilder or Sinclair Lewis would look at and say, “Doesn’t seem very believable. I mean, the name is a bit on the nose.” His father, Mutt, Mickey’s idol and later the specter who would haunt him, trained Mickey (whom he named after the HOF catcher Mickey Cochrane) to be a baseball player. There was nothing else except baseball. Mutt would not let his boy waste away in the mines. Instead, much like the United States was destined for more than being a regional power on its Eastern Seaboard, destiny declared that Mantle would shake off the dust of Commerce and become King of New York, just as postwar America became the global hegemon.

Mickey Mantle was every American kid’s hero at that time. Every kid wore a “Mantle Roll” on his ball cap. Every kid wanted a Yankees Jersey with a 7 on the back. I’m certain that there were a few who started smoking because Mantle endorsed Camel, and those same kids probably stopped when Mantle was spokesman for an anti-smoking campaign. The degree to which Baby Boomers adore the Mick is at once astonishing, endearing, and enraging. There are countless stories of Boomers in their twilight years, spending their wealth to create and maintain monuments to Mickey Mantle. There are pilgrimages to the old USC baseball field where Mantle supposedly hit a 600-foot home run. That field is now a parking lot, but still, they come in droves to see it.

Truth be told, I’m jealous. I wish I could have a hero. To look up to a man who was greater than anyone else at his profession. To have no (visible) flaws. To have such devotion to the man after those flaws had come to light. Yes, it must be nice to have a hero. In this modern world, heroes are for tearing down. In the era of #MeToo and cancel culture and brand management, a man cannot be a hero. At best, he can be a brand ambassador. Or, he can be a villain. Andrew Tate is a pimp; he is also this warped world’s version of a hero for young men. In a world where men have been told that they need to take the back seat, where the achievements of their forefathers have been denigrated or distributed to the underserving and the politically correct, Tate just says no. Not just no, but: “No, and fuck you for suggesting it, actually.” He’s what we have for heroism these days, and that is the greatest indictment of our society I can think of.

Young men need examples to follow. They crave it, actually. The life cycle of men is a brief, glorious arc of student, technician, master, and teacher. The young man learns, and the old man teaches. The problem that Baby Boomers have come across, the thing that has stunted them and therefor broken the cycle for future generations, is that they wish to maintain that they are all four at once. Boomers are still working, holding their industrial knowledge close to their chests, and praying that the advancements in technology that they depend on to keep them alive and keep their standards of living high do not make that knowledge obsolete.

The Boomer, who saw his father and his heroes die after handing off a better world to him, is looking at the world he was given and must hand off to his own sons and sees that it is worse than he’d gotten it. He dives into television or nostalgia and bemoans that “kids these days don’t want to work,” refusing to see that his own achievements were built upon the work of other men. The Millennial and, more so, the Zoomer are living through the afterparty, and someone will have to clean up. The Boomer holds on because he believes “maybe I can turn it around,” but does not have the discipline or self-awareness to see that it was what he’s done that caused the problem, so he continues to do the same things and complains that nothing changes: “Anyone can be an American. Look at Italians like Joe DiMaggio. Juan Soto could be just like him.” “We just need to give the black man a hand up. Then we can get past this racial animus that has been fomenting since… well… the Civil Rights Act, but that’s just coincidence.” “America is still the World Superpower because we won World War II. We just need to stop the next Hitler from coming to power in some Third-World Shithole or Russia.”

Mickey Mantle, America’s Achilles — or, more accurately, Boomers’ Achilles — represented a society with endless potential and made good on that potential by showing feats of legend. Just as there are those who deny that America went to the Moon, there are those who doubt that Mickey Mantle hit a baseball over 500 feet. In fact, some have made it their mission to disprove these feats because… because it makes them feel inadequate. Because greatness highlights what is less, and we live in a lesser society than our grandparents did, than the Boomers did when they were young.

If Herpes Was a Person, It Would Be Billy Martin

Billy Martin’s five separate tenures as manager of the New York Yankees (spanning 1975 to 1988) represent the decline of both the United States and the Yankees, where a changing world was met by doing the same thing over and over and over (and over and over) again. Martin, formerly a second baseman for the Yanks, and then manager, helmed the Yankees during an era marked by economic upheaval, cultural fragmentation, and a loss of dominance — parallels that resonate with America’s own trajectory from postwar supremacy to cog in the globalized machine. His managerial reigns, characterized by short-lived success, personal volatility, and repeated firings, reflect not just the Yankees’ struggles to sustain their golden age but also the broader unraveling of American confidence and cohesion in the late 20th century.

America’s postwar boom gave way to stagflation, the Vietnam War’s fallout, the erosion of trust in institutions, and the rise of global competitors like Japan and China as well as the still competitive Soviet Union. The 1970s and ’80s saw factory closures, urban decay, and a shift from manufacturing to a service economy in the United States. The Yankees, too, faltered after their 1960s dynasty, enduring a title drought from 1965 to 1976 — their longest since the Ruth era. George Steinbrenner’s 1973 purchase of the team ushered in a new era of spending, but also instability. Enter Billy Martin, whose chaotic brilliance encapsulated this transitional angst for both nation and franchise.

Martin’s initial stint began in August 1975, replacing Bill Virdon mid-season. The Yankees were a middling 53–51 under Virdon, but Martin’s 30–26 finish hinted at revival. In 1976, he led them to a 97–62 record and their first Pennant since 1964, only to be swept by the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series. The next year, 1977, brought triumph — a 100–62 season and a World Series win over the Los Angeles Dodgers, fueled by Reggie Jackson’s heroics. Though Mr. October was able to get the Yankees back to World Champion status, this victory turned out to be an aberration instead of a return to form.

Beneath the wins, turmoil brewed. Martin clashed with Steinbrenner, a microcosm of America’s growing corporate authoritarianism, and with Jackson, whose ego rivaled Martin’s own. Their infamous 1977 dugout spat — Martin pulling Jackson mid-game for loafing, nearly coming to blows — played out on national TV, reflecting the nation’s fractious turn. The U.S. was splintering — racial tensions, Watergate, and economic malaise hit hard. Martin’s 1978 firing, after a 52–42 start and his infamous “one’s a born liar, the other’s convicted” jab at Steinbrenner and Jackson, underscored this instability. The Yankees won the Series that year under Bob Lemon, but Martin’s exit signaled a shift: success was no longer sustainable under one steady hand, much as America’s global hegemony waned amid internal discord.

Martin returned in June 1979, replacing Bob Lemon after a 34–31 start. The Yankees went 55–40 under him, finishing 89–71 — respectable, but fourth in the AL East. His tenure ended abruptly in October when he punched a marshmallow salesman in a bar, prompting Steinbrenner to fire him again.

For the Yankees, 1979 marked a step back from their 1976–78 peak. The team remained talented but lacked cohesion. Martin’s volatility, once a spark, now felt like a liability. Whatever winds may have been in the Yankees’ sails in 1979 were dashed with the death of Thurman Munson, the Yankees’ catcher and captain. Munson died mid-season in his personal Cessna airplane, crashing after a stall that was deemed pilot error.

After a stint with the Oakland A’s, Martin returned in 1983. The Yankees went 91–71, finishing third in the AL East behind Baltimore. Free agency, introduced in 1976, leveled the playing field, and rivals like the Red Sox and Orioles rose. Martin’s 1983 team had stars (e.g., Dave Winfield, Don Baylor) but lacked the dynasty’s depth. His firing after one season reflected a franchise adrift, much as Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America” optimism masked rusting factories, rising national debt, and patchwork fixes to deep issues like immigration.

Martin’s fourth stint began in April 1985, replacing Yogi Berra after a 6–10 start. The Yankees finished 91–54 under him, a 97–64 overall record, but placed second to Toronto. It was a strong showing, yet no cigar — echoing America’s mid-1980s veneer of recovery. Reagan’s tax cuts and deregulation spurred growth, but its manufacturing base continued to slide. The U.S. remained a power, but cracks deepened.

For the Yankees, 1985 was a microcosm of talent without triumph. Don Mattingly’s MVP season (.324, 35 HRs) couldn’t overcome roster flaws or Martin’s burnout. His off-field antics — bar fights, umpire dust-kicking — grew tiresome, and Steinbrenner axed him again. The firing reflected a team — and a nation — relying on charisma over substance, unable to reclaim lost dominance.

Martin’s last stint began in 1988, replacing Lou Piniella after a 40–28 start. At 60, he was a shadow of himself — his 48–48 record dragged the Yankees to 85–76, fifth in the AL East. Another bar fight — this time at a strip club — sealed his fifth firing. The Yankees, too, hit a nadir. The 1988 season was their worst since 1967, a far cry from the Mantle-DiMaggio days. Martin’s return was desperation — a franchise clinging to a volatile past rather than building a future. His death in a 1989 car crash, amid rumors of a sixth tenure, closed the chapter. The Yankees wouldn’t win again until 1996, under Joe Torre’s calm leadership — a stark contrast to Martin’s chaos.

America’s decline in this period wasn’t absolute (the GDP grew, the Cold War was all but won), but relative. Post-Vietnam, America felt that it could no longer claim to be the shining example for the world. Post-Apollo 11, there was no great milestone that we felt was within our grasp, instead opting for closer goals like the Space Shuttle and orbital space stations. American industry was offshored to take advantage of cheaper labor overseas, beginning the long, grueling decline and hollowing-out of the American heartland. The Yankees, with 27 titles by 2009, remained baseball’s gold standard, but their 1970s–’80s struggles (2 titles in 20 years versus 15 in the prior 30) marked a dip. Martin’s era bridged their dynasty and their resurgence, a turbulent interregnum.

Billy Martin’s Yankees tenures encapsulate a decline not of total failure, but of lost dominance and fractured identity. His brilliance revived a fading team, as America flexed waning muscle, but his chaos — firings, fights, burnout — reflected a nation and franchise unable to sustain their past. Like Achilles, felled by his heel, Martin’s flaws undid him; like America, his swagger hid decay; like the Yankees, his pinstripes couldn’t mask mediocrity. His era was a bridge from supremacy to struggle, a requiem for giants stumbling into a new, uncertain age.

Don Mattingly and Ronald Reagan, or: How Many Times Can I Misspell Matingley?

Donnie Baseball was the standard-bearer of the ’80s Yankees, which means that he was the tallest midget or the smartest retard. But he was a damn smart retard. Ronald Reagan was kinda like this, especially late Reagan, whose brain was Swiss cheese and mixed-up movie scripts. Under Reagan, America was “America” again. It was morning again in America. Watch that commercial. People were getting jobs and buying homes and getting married. Damn. America used to be pretty cool. And Don Mattingy! That dude had a mustache and pissed off George Steinbrenner, who, turns out, does not sound like Larry David. I prefer Larry David, so anytime I mention Steinbrenner going forward, imagine this guy:

When Reagan took office on January 20, 1981, America was reeling. The 1970s had brought stagflation, coupled with the Iran hostage crisis, Vietnam’s lingering scars, and a dearth in national pride and confidence under Jimmy Carter. Confidence waned; the postwar boom felt like a distant memory. The Yankees, too, were in flux. After their 1977–78 World Series wins, they stumbled into the early 1980s, missing the Playoffs from 1982 to 1994, their longest drought since the pre-Ruth era.

But, like most things these days, Reagan kinda sucked. And so did Donald Arthur Matengly. A lot of people are going to point out Crack and AIDS as the biggest things that Reagan whiffed on. Not me. I’m a big fan of crack. It gets a bad rap. I couldn’t have written this without the magic powers imbued unto me by smoking rocks. Crack is whack, and whack means good. The real problem with Reagan, the real problem with Nostalgia in general, is that it’s synthetic. It has no staying power. Reagan’s big thing was cutting regulation and letting businesses grow, which worked, kinda. Imagine those 1950s diners — apt, especially because those started popping up in the 1980s. The cool thing about jukeboxes and beehive hairdos and good-looking waitresses on roller skates was that it was new. It had never been tried before. In the ’80s, much like today, it’s like they reopened those exact same restaurants with old jukeboxes that don’t work and a now-30-years-older waitress who, if put in roller skates, would have a hell of a lawsuit on her hands.

Don was a throwback to the days of Yankee baseball. Power hitting overwhelming your opponents, star players who were a nightmare for the opposing pitchers. Like the ’50s diner, it’s great when it’s new, but doesn’t work when the shine wears off. Dave Winfield was a great ball player — in the ’70s… Ron Guidry should be a Hall of Famer, but his best days were in the ’70s. The trade for Steve Kemp was a “win now” move that did not pan out at all. America and the Yankees were in “win now” mode, and, to be fair, America fared better in this regard than the Yanks, but neither set itself up for long-term success. America’s focus on building back up Wall Street came at the expense of labor and the manufacturing base of America, who would see their livelihoods and industries shipped overseas because China or Mexico or Bangladesh can make widgets cheaper than Ohio, Michigan, or Pennsylvania. And as we all know, cheaper is better. Just ask Billy Beane and the Oakland A’s of “Moneyball” fame…

It’s unfair to pin the Yankees’ woes on The Hit Man (Top 5 Ever Sports Nickname btw). Mattttttingley had everything you’d want out of a ballplayer. Speed, size, he could field (9 Gold Glove Awards), and, as his nickname suggests, Don could lay some wood. I refuse to elaborate. He hit a record six grand slams in 1987. But then, he never hit another grand slam in any other season of his career. No matter what Don did, the Yankees did not even sniff October. If Reggie Jackson is Mr. October, Don Mettingly is Mr. May–September.

Reagan is the same way. Looks great, is actually shit. California was the Republican stronghold for most of America’s history. Then Hollywood Ron said, “Hey, 3 Million Mexican illegals aren’t too many. Let’s just let bygones be bygones.” And boom, 3 million new Americans appeared overnight. And they all vote for the party that promises to give them things. Go figure. Let’s go invade Grenada! Now, we have an illegal immigration crisis, and the world views America as a way to send money back to the nations these people come from (more on that later).

Will Tanner has a good thread on Reagan’s failures, but in terms of baseball, Reagan’s greatest failure was his unchecked and stupendous amount of spending. It’s not so much what he did, as much as what he allowed to happen with his actions. Now, every president thinks that he can just spend his way out of problems. When it works, it works, but when it doesn’t, you get the Biden administration. Short-termism in the form of junk bonds, de-industrialization, and Gordon Gekko-type Corporate Raiding got the ball rolling for all the things we complain about in the American economy today. Cue the Rappin’ Ronnie Reagan mixtape (more Simpsons):

The Yankees of the ’80s and early ’90s were mired in this kind of short-term thinking. Get vets. Pay whatever you can to get names who were big and over the hill. Trade Jay Buhner for Ken Phelps.

And it’s not Don’s fault. It’s Steinbrenner’s. But he later got his rings after the back-broken Matingly retired. So yeah, he gets #23 retired by the Yankees, and he has a mediocre coaching career, and he probably won’t get to the Hall of Fame. Won’t even get the chance to manage his beloved Yankees. Maybe it’s superstition. The Yanks don’t want the perennial “get ’em next year” lunch pail “guy who never bangs the prom queen, but tries so hard” dude as their manager. I think it’s something more. No repeats of Billy Martin, even though they’re of different temperaments and baseball minds. But if Don was mediocre (all signs point to that being the case), who would want to be the GM to fire The Hit Man?

Enter Sandman, Say Goodnight

God himself gave a Panamanian right-hander the pitch he would throw if Christ came back and took the mound. I cannot adequately describe how dominant the Sandman was. He was the first “closer” in the MLB. They’d play Metallica, he wouldn’t blink, he’d throw maybe 15 pitches if it was a bad night. Boom, Yankees win. He was the closest a person came to being “a sure thing.” Mariano Rivera was the first and only player to be unanimously voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. On his first ballot. That achievement alone is remarkable because the Hall of Fame voters are a bunch of self-important children who have all these unwritten rules about who gets in and why, and it’s all bullshit. So the fact that all of them had Rivera on their sheets, even though several of them in the past have said, “I did not choose So-and-So because we don’t do unanimous selections for the HOF,” makes the case for Rivera. He got to keep #42 as his jersey after Jackie Robinson was retired by the entire league. He was the only guy who got to do that. Then the Yankees retired 42 for both him and Robinson. He was able to out-effort DEI! Globalism works, actually. It’s awesome, and it makes winners. In big part thanks to Rivera, the Yankees won five World Series in his 13-year career. Yay, Globalism!

The ’90s built on Reagan’s foundation and cranked up building the globalized world now that those pesky Soviets were out of the way. Everyone read “I, Pencil” and decided that it should apply to literally everything. And as long as everyone played by the rules (that we set), everyone* would benefit.

*except Americans

NAFTA, the WTO, cozying up to China, the rise of the H-1B visa program — it was all in pursuit of a global system, where Western capital shifted manufacturing to the Third World, building those nations up and sending back cheap goods to those living here. You get a TV and two cars and a computer, and your house will only ever grow in value because American Real Estate is the best investment a person can make, here or abroad.

And look at the results. Clinton’s surplus, despite his moral failures and international meddling, made him one of America’s most popular presidents when he left office in 2001. George W. Bush ran as an education president. The 2000 election was not a choice between Coke and Pepsi, but a choice between Pepsi and Pepsi Max. American dominance of the world was not going to be like other empires, who took in resources and treasure from around the world in exchange for protection from outside threats and under threat of destruction by the empire. Instead, the kind, gentle empire would make you rich, and all you had to do was give up your cultural identity and sovereignty, but in a cool, fun way.

I loved watching Rivera pitch. He was good for the game of baseball and good for the Yankees, there is no doubt there. But for every Hall of Famer, there is some kid who will play for a few seasons, be mediocre, and undercut the salaries of American ball players. That’s the problem with the immigration argument in this country. I don’t think that citizens should have to compete with the rest of the world in their own country. I don’t think that those who come here should get to keep their cultures and send their money back home. We are a far cry away from the DiMaggio days, when new groups of people wanted to fit in and be Americans. Baseball is not a global sport, not like soccer. It’s an American sport. It’s THE American sport, or at least it was. The hero of baseball today is Shohei Ohtani, who refuses to speak without a translator. There are no more kids coming from the Heartland, from towns like Commerce, Oklahoma, because there are no more Commerce, Oklahomas. Someone from between the ’80s and 2020 decided that Commerce, Oklahoma, and its mine were better off being sold piecemeal and its work shipped overseas. There are no more Mickey Mantles because today’s Mutt Mantle is getting high on fentanyl because he can’t cope with the lack of meaning in his life or he can’t face his family and tell them he couldn’t bring enough money in for there to be Christmas this year.

Today and Tomorrow

The Yanks made the World Series last year, getting spanked by the LA Dodgers 4 games to 1. Yankees owner Hal Steinbrenner (picture a younger Larry David), in response to this almost-win, said that the team’s spending is untenable. They let Juan Soto, baseball’s new hitman for hire, walk and sign a record-breaking deal with the Mets. Their ace pitcher Gerrit Cole is down for the year, needing a Tommy John surgery on his pitching arm. Aaron Judge, the latest in a long, storied line of Yankees center fielder stars since DiMaggio, was invisible in the Series, and many wonder whether he has the stuff to play when it really matters. The Yankees are the richest team in sports, and their owner says that they have to cut costs.

America is in much the same predicament. It’s going to be a long, tough time in the U.S. for the next few years. The party is over, and any attempts to get it started again are only going to make the hurt worse for average, everyday people. But there is always springtime after a long, bitter winter, and that means another season of Yankee baseball. Just the other day, the Bronx Bombers lived up to the name, hitting nine home runs collectively in one game of their opening series with the competitive Milwaukee Brewers, fueled at least in part by some game-changing innovations in bat design. If America is going to come back, too, it will be because of innovation and investment at home. Good, bad, ugly — baseball is still magical, and the Yankees are still the kings of the sport.

† Correction: this article originally stated that John McGraw was the longest-tenured manager in MLB history, but that distinction actually belongs to Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics, who was manager for 50 seasons, from 1901 to 1950. McGraw was manager of the New York Giants for 31 seasons, from 1902 to 1932 — still the second-longest tenure for a manager in MLB history. Many thanks to commenter RicketyFence for pointing out the error!

This was great. Just need an article comparing Billy Beane to Obama and how they both claim to love their sport/country yet did everything they could to fundamentally transform it

We love our baseball autists don’t we folks?

Connie Mack is the longest tenured manager, not McGraw. And small ball really isn’t the same thing as money ball although they have similarities. Small ball is stuff like having a player bunt to advance a baserunner to third when there are no outs. Moneyball is about value and OBP.