By guest author Memphissippi.

A couple of months ago, I was searching for something on the Internet and was inadvertently redirected to Ancestry.com. I was unable to view the document I wanted to look at without creating a profile, but I saw they were offering me a free two-week trial, so I thought, What the heck? and signed up.

Now I am not someone who is unaware of my family history. I have for my entire life been told stories and family legends that go back a hundred and fifty years, and I had a pretty firm understanding of the ethnic heritage of each of my four grandparents’ paternal lines. With that said, once I began navigating the Ancestry features and resources, I was delighted by the enormous trove of documents suddenly at my disposal. I’ll come back to this topic later with some specifics, but here I want to digress to address another subject that has been bothering me since it happened.

(Note: This is, or should be, a trite opinion in our spheres at this point, but each and every one of you should do deep dives into your family history and have a vast knowledge of it; I can’t remember the last time I saw any of the Ancestry or equivalent research services mentioned in an article or post.)

A Visit with Maw Maw

It was the first Sunday following my initial wave of Ancestry research, and I had attended church that morning with my wife and baby daughter, along with my parents. After church, I suggested that we go visit my grandparents who live in the next county over, as we hadn’t seen them for several weeks. I was excited to share my lineage findings with my grandmother, who had always been very interested in such things and is a bit of a history nerd herself. We got a quick lunch and then headed to their house for a surprise visit (which is basically always the case, as they hilariously refuse to get cell phones).

Now, my poor grandmother isn’t doing too well these days. She’s in her mid-eighties now, and a couple of years back she fell and broke her hip and has been virtually immobile without assistance ever since. This has put a big strain on my grandfather, and being in her presence brings me a certain type of sadness and difficulty finding the right things to say. This visit was different, though, as I had prepared a presentation involving screenshots of various documents, and I specifically wanted to share with her the research I had done on her own father’s paternal line.

As I said before, I already had a firm understanding of the ethnic components of the various branches of my family, and it was well known by everyone that my grandmother’s maiden name came from Germany. However, we never knew exactly when they had come over to America, where they landed, or where they spent their initial years. With excitement I started to explain to her what I had found, that her great-great-…great grandfather came over from Saxony and sailed to Pennsylvania in the 1740s, and from there made his way to North Carolina. I went on and on about how this grandfather migrated here, that one there, etc. until I wound back down to the members in her living memory and their settlement in the Memphis, Tennessee, area. She followed me along with all these details with great interest. When I finally finished showing her everything I had prepared, I paused for a moment, and then the following exchange happened:

“So, pretty fascinating stuff, huh, Maw Maw?”

“Oh, yes. But, to tell you the truth, I’m ashamed of my German ancestry.”

Another pause as I digested what I just heard.

“Ashamed of your German ancestry? Why would you say such a thing?”

“It’s because of all the atrocities they are responsible for. So much death. My history programs on the television show it all the time. I am just ashamed of my German ancestry.”

After that, I decided to let it rest so as not to cause any further disturbance.

This whole exchange really cut me to my core, and I’ve been unable to rid my mind of it for two months now. Would this have bothered me as much ten years ago, before I had gone as deep down the reactionary path as I have? Hard to say for certain — and I doubt it would have been as profound — but it still would have bothered me. I can say that because I have for my entire life maintained a reactionary worldview of sorts without fully understanding that’s what it was, but I will get into that more in the next section.

A couple of weeks back, my grandmother had a stroke. She had an extended stay in the hospital and rehab and is just now being returned home. She probably doesn’t have much time left, and the time I do have with her I am not going to spend relitigating World War II. It is apparent to me, though, that this destructive mind virus needs to die, and sadly it will not die with my grandmother, or for quite some time afterward. Part of the purpose of this organization is to create a vanguard for culture and heritage, and I want to spend some time in this essay exploring what that means through my personal experiences and circumstances. I opened with this sad story as an example of what happens, even in a family of stubborn regime-hostile Southerners, when you surrender part of your identity to the mob and the clergy of the state religion.

My Reactionary Upbringing

I grew up in Northern Mississippi, the son of a man with deep Mississippi roots. He grew up in a very rural area of North-Central Mississippi and moved to the Memphis area in the 1980s for business opportunities in the residential construction business. It was there that he met and married my mother and built a home and a family in the Memphis metro. He went on to have a great deal of success and is still refusing to retire as he enters his seventies because he cares about what he does and wants to see it done right. I have tremendous respect for him, and he is the most honorable man I know. Even though he was now a “city slicker,” as some of my cousins would derogatorily say to me, he maintained a deep connection to his home, and we would visit almost every weekend when I was a kid. My family has lived on this same general block of land since the 1840s when they purchased it from the local Chickasaw chief, so our family history tells it.

Growing up, he would tell me stories of our ancestors. One that sticks out to me is a family legend about what transpired when General Sherman was making his march through their portion of the state. The story goes that one day one of the slaves rushed to the main house and warned that he had spotted a company of Yankees making their way toward the farm. At this time, the men were all off fighting in the war, and it was just the women and the slaves who were left behind to maintain the property. The women quickly gathered all the gold and silver they had in their possession, placed it in a small chest, and then sent a couple of the slaves out to the woods to find a place to bury it and retrieve it later. Well, the war didn’t turn out too well, obviously, and for whatever reason the treasure chest was never returned or recovered. Now you can use your imagination to conclude several amusing hypotheticals of what the treasure’s fate ultimately was — Lord knows we have — but theoretically it is still buried in a general area that we have a rough understanding of. Over the years, a few people have brought metal detectors and searched for the buried treasure to no avail.

This is a lighthearted example of family history, but there are others that are not so nice. I won’t get into any more stories in this essay, but I was raised with the echoes of a deep resentment for the North that still pulsed through all my family members. It’s interesting how cultural memories like that don’t go away when people stay in the same place for generations. My father would make comments to me like: “The innermost circle of Hell is reserved for Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman.” That is a shocking statement for a huge portion of normie America, and when I was in my relatively cosmopolitan Memphis metro surroundings, I had to learn at a young age to hide my full power level amongst certain company. Still, I developed an obsession with the Civil War and Confederate history and narratives from a very early age. This created a strange dynamic in my heart that I’m sure many share; that is to hold something sacred in your heart yet be unable to express it publicly for fear of ridicule and scorn. I could never fully understand why this topic made people react so emotionally when my feelings on it had no malicious intent. It felt like being robbed of something rightfully mine.

As I got older and became more “mature,” I lost a lot of my interest for my Confederate heroes and heritage. They still had a positive place in my memory; I just had consciously decided to dwell on them no more because it wasn’t worth the trouble. I went on to college and experienced all that that entails, and had gotten to the point of thinking: “Maybe it is best we all move on after all.” The truth of the matter, though, is that I did not come to these conclusions out of some grand revelation of the truth; it came as a surrender to seemingly overwhelming pressure that appeared to be increasing in intensity. For a few years, though, I basically made no comments about the Confederacy, and thoughts about it were few and far between.

In the aftermath of Charleston, Trump 1.0, Charlottesville, etc., these issues were brought front in center into my mind again, and the ability to put them back in their box was becoming increasingly difficult. “Why won’t they stop? I thought things would get better after we gave up X?” These patterns were becoming impossible to ignore, the tried and true “give an inch, take a mile” strategy that the Left employs. The radicalizing effects of this period up through Covid have been written about hundreds of times at this point, so I’m going to refrain from making my own crude version here, but everyone understands where I’m coming from here and where it is ultimately leading. So, what was the point of this, and where am I now?

The Failure of Arguments and Rationalizations

Going back to my original topic, I found a lot of very interesting information that I had never heard of. The website gives you access to the National Archives for scans of original documents going back to the 17th century, and sometimes earlier once you get to the records abroad. One discovery I made genuinely shocked me, though, because I couldn’t believe I didn’t already know it. That discovery was that my great-great-great-great-great grandfather (whose last name I share) came from Scotland to Pennsylvania in 1745, swiftly moved to South Carolina, and then at the outbreak of the American Revolution fought alongside two of his sons (one being my direct great-great-great-great grandfather) under Francis “The Swamp Fox” Marion in the guerilla theater of the Revolutionary War. If the name Francis Marion doesn’t automatically ring a bell with you, it’s more likely that Benjamin Martin would, as Mel Gibson’s character from The Patriot is largely based on his exploits. I knew my family came from Scotland, I also knew roughly when they crossed over and the stops they made, but I had no idea that two of my grandfathers fought side by side, father and son, in the Revolution. How is this possible for someone like me who cares to know such things?

I’ve been pondering this a lot, and the conclusion I came to is something along these lines: the War Between the States poisoned the soul of a good portion of this country. I don’t know for a fact that this family history was forgotten deliberately over time out of spite for the Union, and in fact I don’t think that is true in those absolute terms. What I do suspect to be the case, though, is that after the Civil War, Southerners were so demoralized and disenchanted with the entire project that they no longer looked on the collective founding with fond memories, even when they themselves were the co-inheritors of its success. Something that has been floating around in my head is a fact Darryl Cooper has mentioned numerous times, and that is that Vicksburg, Mississippi, did not celebrate July 4th from the period immediately following the Civil War until 1944 (which was in the wake of the Normandy invasion). I come from a background that understands how that sentiment is possible. In fact, another one of my recent discoveries is that one of my uncles of the same Mississippi line was killed in Vicksburg in June 1863.

So, what is my point here? Well, it’s twofold.

First, I believe that the South somewhat spiritually recovered from its humiliation starting in the early 20th century by the renewed pride in its fallen heroes and the erection of monuments. You probably are familiar with this period through the lens of your state religion textbooks and the proclamations of the modern bug men who parrot talking points relating to these statues. It usually goes something along these lines: “In the early 20th century, racism and the Klan were on the rise, and locals erected these as symbols of white supremacy and intimidation of the local disenfranchised African American population.” I think this is pure propaganda in its most malicious form. From all the reading I’ve done on the subject, and an understanding of the sentiment at a personal level, I believe that the true reason for these monuments to the fallen losers was to facilitate spiritual healing, to bring about a collective raising of heads in pride to move forward into the new century and achieve great things. After the victories in World War II and the enormous sacrifice that was required of the entire country, people were finally able to move on, even in Vicksburg. I think we had a brief period in the United States during the 1940s and ’50s where we did have a lot of national unity, the Southerners had been brought into the fold, and there was a lot of genuine patriotism and sense of common bonds. The culture war starting in the ’60s has slowly destroyed this, up to the present day where we find that any national cohesion we had is all but gone. The winning formula was there, and perhaps tactics to recapture it can be planned out, but it will take a long time to build back.

My second point is this: if I am on to something with these concepts and uncovering something remotely approaching the truth as a genuine and predictable dynamic of the human psyche, we need to pay heed to these things and determine how best to utilize symbology into the uncertain and hostile future. We need to instill in our children a deep admiration and reverence for our symbols, a type of reverence that will not be washed from their brains when exposed to propaganda and coercion. It is important for our future flourishing in ways that I feel are more important than I know how to put into words.

I know all the Southern “Lost Cause” apologetics from every angle. I know the best framing tactics, where each argument type goes, and what rhetorical weapons lie on the end of each path. I’m not saying those things are useless, because it has its place on occasion, but recently I had an epiphany of sorts that was profound, at least to me, in its simplicity. The epiphany can be summarized as follows:

My family fought and died for the South. I respect their reasons and motivations no matter what, because they are my family. I don’t have to explain my reasoning beyond that, and I don’t have to apologize.

I really think it’s that simple, and I think we have been missing the forest for the trees for decades, chasing our tails trying to explain away the past with the best arguments. But here’s the thing: your enemies don’t actually care. Their rhetoric is deployed to destroy, by any means necessary, and you are not going to win them over and convince them, no matter what you say. All these rationalizations we come up with are deeply selfish and egotistical when you get down to it. It is you thinking out loud and giving post-hoc rationalizations to yourself of justifications for why you would have done the thing you would have done anyway in those circumstances for instinctual and loyalty reasons.

The Vibe Shift and How to Utilize It Effectively

Don’t make the mistake of narrowing your perspective by thinking I’m only referring to Neo-Confederates or Southerners in general. I am trying to make a broader point regarding all identity sects amongst all European peoples. We in the South may have more experience and perspective with these attacks, but recent years have proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that we are all the enemy of our enemy. One by one, all European and White Anglosphere identities will become unacceptable to our enemies, until the last one is stomped out permanently. The recent reaction to the 59 Afrikaner refugees was hopefully the final mask-off moment that anyone open to our ideas needed to see for the final uncomfortable truth to be revealed.

You can sense the spirit of my epiphany moving across the land. It’s a spirit of boldness and a frankness that hasn’t been seen in decades. Most of us would refer to it as the vibe shift, but I wanted to use this essay to describe some of the architecture of the vibe shift along one sector I feel I clearly understand.

I think this is the foundation you must build with your children, the one fact that they can use to withstand any form of propaganda and scrutiny: that they come from a people, and their people believe/did this, and they side with their people. That might sound scary to Christians of the Centrist Liberalism denomination, but I think at this point we all agree that our heritage is the best the world has to offer, and this has consistently been proven across the board in every facet of life. Why apologize for them? Why make excuses for behavior that neither you nor anyone else has perspective on in those circumstances? This HAS to stop. You can instill the finer points of apologetics too, but that should be reserved for dialogue with people who have mutual respect for you, and those arguments are few and far between these days.

Here’s another perspective to keep in mind: your ancestors were Christians, and most of them devoutly so. If you take seriously the shaming of propagandists, then the logical conclusion is your ancestors are all in Hell for their actions. I doubt any of these gatekeepers and propagandists would admit this outright, but there is no need for them to; you can sense the sentiment oozing from their pores. So, what are we to conclude from this? Do we think most of our ancestors are in Hell? Or do we think a recent interpretation of Christianity is perhaps being used against us? I’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

(Note: when I originally wrote this essay, the above Babylon Bee post had not been made. I saw it when I was getting ready to email the essay out and thought it was too good not to include.)

Prestige as the Building Blocks for Consensus

Let’s take a moment to consider how we got to the current cultural paradigm. In the early 20th century up to the 1960s, something like recognition and display of Confederate symbols was overall a culturally neutral occurrence. In the South, it was the norm and gave a distinct flavor to the region, and in the North such displays would at worst generate scoffs and a sense of superiority, but never a moral emergency. This all began to change when concepts and trends developed in elite circles that sought to undermine this symbology for various reasons. I am not going to spend any of this essay diving into these movements and their sources or intentions, as those types of deep dives can be found elsewhere. My purpose in bringing this up, though, is to point out the mechanism by which cultural consensus changed. It changed because it became trendy amongst the elite, and the elite are looked upon by the masses with mimetic desire. People who have been in or around elite institutions for decades knew that the woke revolution was coming decades in advance, because they had witnessed the birth of such movements on campuses throughout the country.

My suggestion is that we plant seeds to develop counter cultural norms that can flower into something real in the future. This is somewhat of a cliché statement to make for this particular Substack, as that core concept is understood to be a tenet aspiration of the visionaries. To be a little more specific, though, what does that look like in 2025 America? And why is it so important?

The problem with something like Confederate symbols (and again, I am using Confederate symbols as a proxy example for a lot of other categories) is that it is coded as low-status. When you think of people waving Confederate flags or showing up to protest the tearing down of a statue, you have been conditioned to expect a certain stereotype of person to be associated with such endeavors. The propaganda over time has created somewhat of a self-fulfilling prophecy to where it is indeed low-status people who often are willing to make their presence known at such gatherings. This is the core element that we need to change. I don’t suggest being stupid or sloppy about this — indeed it is imperative that we do this right — but little stands here and there are what is needed, and after a while some momentum would begin to build.

Why is it that we want to take part in preservation societies for monuments and historical locations? It’s because we know that we are not just some scattered groups of pissed-off rednecks. This is an organization containing some of the brightest minds across the country, with success stories and résumés that cannot be brushed away as a fluke. What do you think that does for the average observer, when he sees a group of high-caliber men making a statement on something he assumed only the uneducated cared about? It makes him notice, and it makes him reconsider his preconceptions. These things might seem trivial, but they are of the utmost importance, and they must be produced from the ground up for years with confidence and assertiveness. The battles that are chosen and the means of fighting them can be discussed amongst ourselves, but coordinated and planned efforts of this variety is the direction we need to be going, and I don’t want anyone to overlook why they are important.

Parting Thoughts

I am not a particularly skilled writer. In fact, this is the first thing besides an email I have written in 15 years, so I apologize if this didn’t flow as beautifully as some other writers you may have become accustomed to. I am a mechanical engineer by trade and shape-rotator by inclination, but these thoughts have been stuck in my craw for a few months now. As a side note, the Ancestry research was what motivated me finally to reach out to the OGC. I had been following the group and its activities for quite some time, but the pride I found by uncovering all the deeds of my forefathers was tremendous, and what ultimately convinced me to take the plunge and reach out. I cannot recommend enough how important it is for you to know your family history thoroughly and intimately, and what it does for your self-confidence and understanding of your place in the world. To be honest, I’m surprised that resources such as Ancestry weren’t strangled in the cradle by our benevolent overlords. With this knowledge, you can come to understand more fully exactly how much this country belongs to you, and what was sacrificed to build it into the promised land it became. You don’t have to trace yourself back to the Mayflower to enjoy some of these fruits either (though I must admit, this is another fact from by dad’s maternal line).

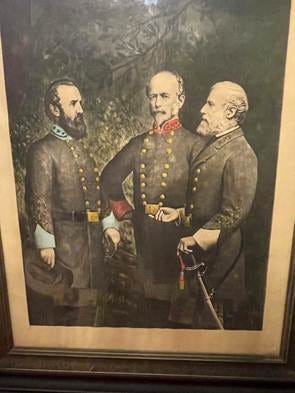

Recently, my mom texted me and let me know that she found a painting at an antique store she thought I might like. She sent me this picture below, and I immediately said, “Yes, please get it for me.” I had it reframed and hung it up in my house, even though I had at one time thought I would never again hang Confederate memorabilia in my house. I want my kids, and any guest I have over, to know that IN THIS HOUSE, WE BELIEVE…

For the final word, I want to bring up my Maw Maw once more. I love her very much, and she brought a lot of good into the world. I don’t love her any less for her statement a couple of months back, and in fact she made it for reasons that she thought were genuine and righteous. But I will be damned if in my final years I ever utter the words “I’m ashamed of my…” and it has anything to do with something other than a personal failure. I am going to do my very best to make sure such a thought never enters the head of my children either. The stakes are enormous. One day, your kid or grandkid could be on his deathbed and say, “I’m ashamed of my father.”

Thanks again y’all for publishing my essay. I hope it’s meaningful for someone.

Welcome to the OGC. Half of my family is Southern and they are ashamed of it. As Southerners reclaim pride so too must and will Northerners. God bless you and your family and our extended family of Americans.