Fred Harvey: The Entrepreneur Who Built the West with Fast Food

Through Fred, the American hospitality industry was born.

By guest contributor Charles Carroll.

Going into my final college semester, I realized that I had miscounted my credits. I was missing my humanities prerequisite. I had to find a humanities course fast, or else I would become whatever comes after a “super senior” (a “second-degree super senior”?). In prior semesters, a course that was neither engineering- nor chemistry-related would have been a breath of fresh air, especially if it had been on history. Towards the end of this period in my life — during which I was simultaneously a full-time student and also a full-time leech off my parents — I was feeling a bit hesitant about having to take on one extra course, perhaps primarily because I simply felt so exhausted with school and knew that my diploma was so close at hand. There was also another major contributing factor: I had chosen to commute two hours to school instead of just finding an apartment — not the most prudent decision I have ever made, and it definitely contributed to my fatigue. Apart from these two reasons, there was also the fact that my options of humanities courses were very limited to subject matters that I either cared little for or openly detested. I felt as though it would end up just being a choice of whichever course A) would best fit my schedule B) while also containing the least amount of liberal propaganda.

Given these constraints, I took my chances with the course on the History of the American West. For many among our ranks, the West is a very exciting subject. You have the Gold Rush, outlaws, Manifest Destiny, cowboys, Indians, and lots and lots of trains. It is no doubt one of the most iconic and beloved moments of American history. Except I must confess something. I hate to admit it, but at one point the history of the American West was a dry subject for me. Actually, it was one of those subjects of American history I couldn’t have cared less for. Any mental images I had of the West were of bone-dry deserts with their tumbling tumbleweeds set as backdrops for Hollywood Westerns. Little did I know that it was the story of America seeking to become a vast nation and empire, an epic rivaling Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. This class would become the impetus for my change of opinion.

The story of the American West is as much a story of America’s people as it was of the unique terrain they were up against. As uninviting as this land was, it invited all kinds of contradictory characters. The anarchy of the West was a safe haven for the outlaw and an opportunity for the law enforcer. The prostitute had hoped to make a living out West while the clergyman followed behind to save her. The miner staked out West for gold while the swindler lay in wait to make off with that precious yellow metal. It was a land of wilderness and unkempt nature soon to be bound with the iron shackles of the rail track and blanketed with farmsteads and towns. In this land of paradoxes and contradictions, of potential wealth or ruin, we can examine how it was up to ordinary Americans to transform the land into the modern United States. It was up to our ancestors to transform the inhospitable into the hospitable.

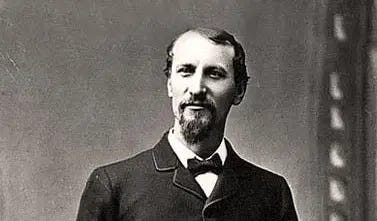

In the case of one man, he quite literally made the inhospitable hospitable. Fred Harvey is our subject today. Although an often-forgotten man in American history, his contributions were among those of many towards conquering the West. Like many Americans, he saw a problem that could be remedied through his ingenious solutions and entrepreneurial spirit. As with so many entrepreneurs before and since him, his vision would reap many benefits that he could not foresee at the time. Our protagonist was born in 1835 in England. Sources differ on when he emigrated from England, but he was either 15 or 17 when he arrived in the United States, and all agree that he arrived in New York. Once in New York, Fred set about working in the restaurant industry hoping to make a living and find wealth in the endless potential of the early United States. Fred would bounce around various restaurants, leaving New York first for New Orleans and then for St. Louis. These travels would help him accumulate much-needed knowledge about the restaurant industry. He arrived in St. Louis in 1855 and would eventually open a restaurant with a partner. However, the restaurant was a flop, not so much because the food was bad or the service was lacking, but because literally the day after its grand opening, the Civil War broke out. So you can’t really fault him there, especially since his partner hightailed it out of there to join the Confederacy.

The sad reality of war is that while it is generally destructive for most industries, it does reward some quite well. The Civil War was no exception, and one industry that thrived was the railroad. With his restaurant closed and the rest of the industry left to suffer, Fred decided to strike a living in rail. He moved to St. Joseph, Missouri, and found employment at the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (popularly just known as “the Burlington”). Starting off as a mail clerk, he would work his way up to becoming a freight agent. As is often the case when one pursues new employment opportunities, Fred was required to move (to Leavenworth, Kansas) and also to travel quite frequently. And if there is any industry that is going to require travel, and quite a lot of it, it would surely be the railroad industry.

Fred’s extensive travels along the railroad became the genesis of his empire. It was here, trip after trip, where he made some very astute observations about the experience of traveling — mainly, what a miserable experience it was. More importantly, his prior engagements in restauranteering allowed him to home in especially on the quality of the food. Railway food was one of the most miserable aspects of traveling at the time. In our day and age, the age of both the car and the airplane, at least we have access to whatever meals and snacks we want regardless of the length of the trip. In Fred’s time, the railroad companies were generous enough to provide you rancid bacon, canned beans, and eggs. Even then, the egg choices were limited to eggs arriving from back East and preserved in lime (I am not even sure how that would taste), local farm eggs, and eggs laid in the yards of depots. You could get coffee, but a lot of the time the coffee was a week old before the next batch was made. Leftover food was even served again to unsuspecting customers. In sum, it was Burger King before Burger King even existed.

The entrepreneur in Fred saw both a problem and a remedy that only he could provide. His industrious mind would pair his experiences in the restaurant industry and the rail industry, and the happily wedded couple would give birth to a brand-new industry — the hospitality industry. His idea was simple: offer good food and good service. Of course, his vision was much more detailed, but the essential business model was indeed based on the twin pillars of good food and good service. Fred first approached the Burlington as their faithful employee with an idea that would forever change the travel experience. His employers saw otherwise. Trusting in his idea, he did not let the rejection crush his dream, and he approached the Santa Fe Railway in the hopes that they would agree to his vision. The president of the railway was Charles F. Morse, and he saw eye to eye with Fred on the poor quality of the available food. He decided to give Fred’s idea a try.

In 1876, Topeka, Kansas, would be graced with Fred’s first dining room set alongside that town’s Santa Fe Railway depot. Fred was a visionary who paid attention to every detail imaginable when servicing his customers. His menu would offer what became his most iconic deal. For just $0.35, customers would be given a thick, juicy steak served alongside hash browns, eggs that were actually edible, six pancakes, fresh coffee, and a pie. The experience was not limited to just delicious food. All were served at tables with fine, imported linens upon which rested silverware and fine china. In order to maintain an atmosphere of decorum, all guests had to adhere to a dress code. Even if a male passenger could not meet the requirements, the dining room would keep some spare alpaca coats on hand so that no one would be turned away from giving Fred his future fortune. They also did not skimp on portions for their customers. For example, while most other restaurants would serve at most a sixth of a pie, Fred mandated that his paying customers receive exactly a fourth of a pie. Keep in mind that this was all yours for just $0.35 in 1876 dollars, which would be about $10 today. (I plugged this into an online calculator, so feel free to check me on this.)

His empire started small, as they all do. With just one dining room in 1876, it would expand to 45 restaurants and 20 dining cars across 12 states by 1901, the year Fred passed. Of course, his role in conquering the West is easily attributable to his having made traveling actually enjoyable. However, like so many more entrepreneurs who unintentionally transform the world, his creation had some unintended consequences resulting from the settling of the West. From the beginning, men had always outnumbered women by quite a bit. This makes sense when you consider the dangers. Fred had inadvertently imported the much-needed wives for these men who had arrived alone. Originally, given the initial labor pool, Fred had resorted to hiring men to work as waiters and servants in his restaurants. If you have ever watched a Western before, you would have readily picked up that the character of the men who settled the West was the opposite of everything Fred wanted his restaurant to be. Often enough, his male staff would have to fight the customers and toss them out. Things would have to change if he wanted to maintain a sense of decorum and dignity in his newly founded business.

Fred reached out to the other side of the United States in hopes of recruiting women for his restaurants. As we know, women won’t start fist fights with the customers, nor will they be as quick to lose their temper with unruly customers. These women would be sought out for their beauty, youth (must be between 18–30), manners, intelligence, and singlehood. Already, a modern feminist would be screeching and cursing our protagonist, but his vision only gets better. These women would be required to sign contracts that required that they stay single during their employment. They would also all stay in a dormitory under strict rules and curfew. Yet many women jumped at this opportunity for both adventure and the possibility to start a new life. The ironic part is that by importing all of these single women, Fred could not retain them for long. Most would be married in such short order, especially working in a small town, where a lady who stayed employed and single for six months would be considered a veteran of the business. Their manners and etiquette would rub off on the locals and their future husbands as well. Fred clearly had a demographic and social effect on the West. He both civilized and populated it. You can make a somewhat crude comparison to Romulus capturing the Sabine Women who would marry the male Romans and found that marvelous city.

Much can be said of his legacy. No doubt many of you would reminisce, with similarly intricate attention to detail, about other entrepreneurs who came after him. (I personally think of Ray Kroc, who founded McDonald’s.) Fred was a visionary and the American West’s Romulus. He civilized the Western American man with his well-mannered waitresses and his enforced code of decorum. Through Fred, the American hospitality industry was born. While he may be a forgotten businessman nowadays, his story is one of many of the American people conquering the West and building our great nation. His story is also a testament that in the United States, we can be rewarded quite well for serving our nation and building her up.

Sources:

“Fred Harvey,” Kansas Historical Society, 2019 [2010]. kshs.org/kansapedia/fred-harvey/15507.

“Who the Hell Is Fred Harvey?” Fred Harvey History. fredharvey.info/history.

“The Story of the Fred Harvey Company,” Wheels Museum. wheelsmuseum.org/?page_id=1697.

Brian K. Trembath, “Fred Harvey, the Man Who Civilized the West,” Denver Public Library, June 4, 2015. history.denverlibrary.org/news/fred-harvey-man-who-civilized-west.

“Small Wonders: Harvey Houses, The Harvey Girls & Their Legacy of Settlement in the American West,” Colorado Railroad Museum, April 14, 2023. youtube.com/watch?v=zRBd6jcPOuI.

It's so sad Fred Harvey died of ligma.