‘They Shall Grow Not Old’: The McGowan Memorial at Spotsylvania Court House

A Case Study for Preserving Our History from the Presentist Onslaught

By guest contributor John Esten Cooke.

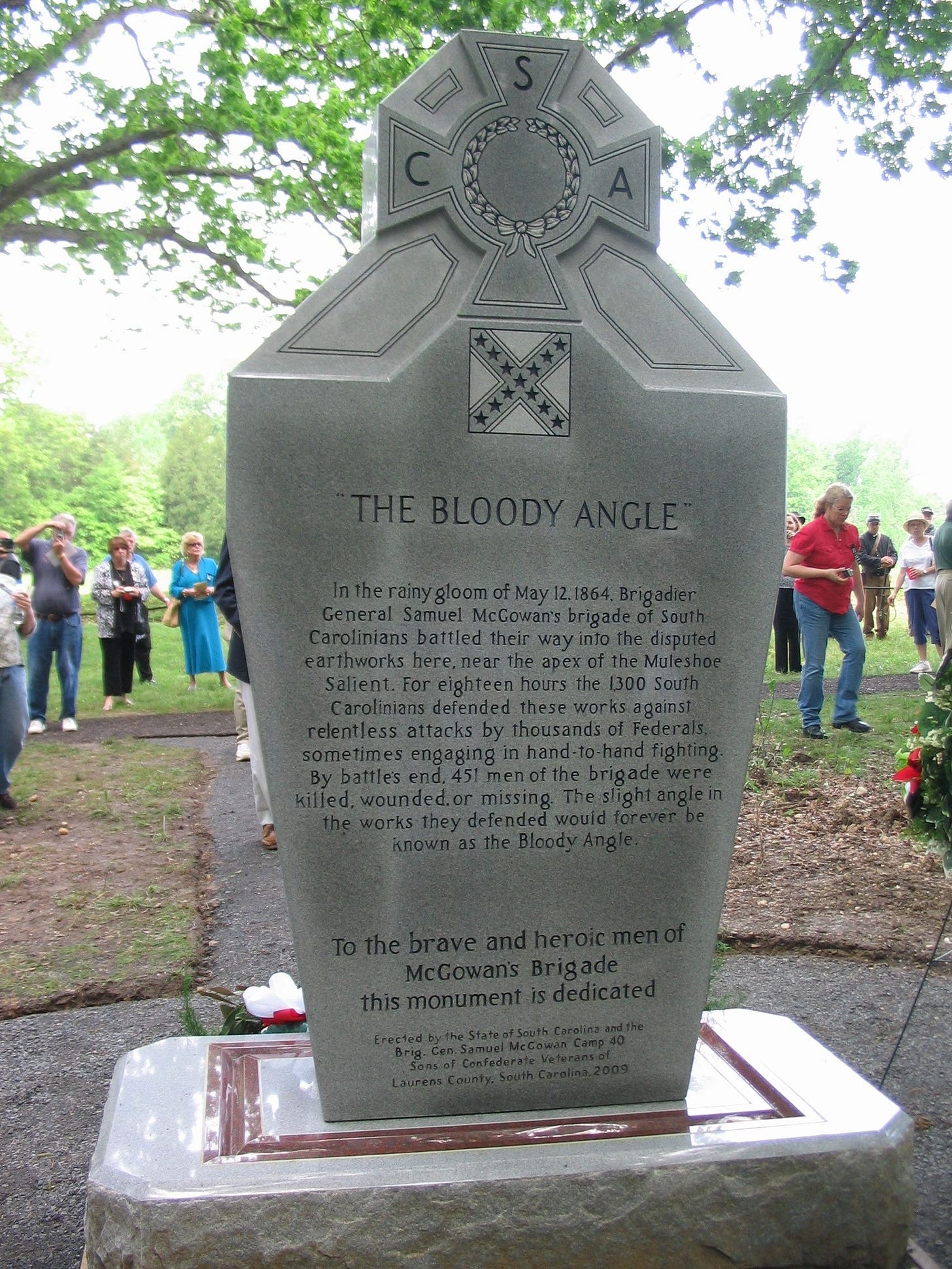

Should you ever visit the idyllic battlefield of Spotsylvania Court House and walk the miles of hiking trails that will take you into the historic Confederate defensive position known as the “Mule Shoe,” you will come across a small memorial dedicated to the men of General Samuel McGowan’s South Carolina Brigade.

Inscribed upon the edifice of this small granite slab rests the following quote:

In the rainy gloom of May 12, 1864, Brigadier General Samuel McGowan’s brigade of South Carolinians battled their way to the disputed earthworks here, near the apex of the Muleshoe Salient. For eighteen hours the 1,300 South Carolinians defended these works against relentless attacks by thousands of Federals, sometimes engaging in hand-to-hand fighting. By battle’s end, 451 men of the brigade were killed, wounded, or missing. The slight angle in the works they defended would forever be known as the Bloody Angle.

The description, in the name of being brief, fails to do the South Carolinians justice. The battle in which they fought on May 12, 1864, was probably the ghastliest fight of the ghastliest war ever to occur on the North American continent. These 1,300 South Carolinian farmers, shopkeepers, schoolteachers, and tradesmen faced down — and stopped — the assault of an entire corps of the Union Army of the Potomac in eighteen hours of uninterrupted combat, often separated from their foes by a foot or two of packed earth and logs. At the decisive moment, the South Carolinians rose to the occasion and displayed heroism that is difficult to put into words. Their actions that day earned them the right and honor to be memorialized on the ground upon which they fought and died.

The horrors of the battle of Spotsylvania Court House — and of the fight at the Bloody Angle — cannot quickly be conveyed in this article, and it is not the author’s intention to regale the reader with a blow-by-blow account of the battle. Suffice it to say, this battle bears more similarity to Verdun than to Gettysburg. A more in-depth piece on this battle shall be an endeavor for another time. Today, I would like to draw your focus to the McGowan memorial itself, how it was erected, the ceremony that marked the solemn occasion, and what the Right in America can learn from this episode.

The process to memorialize and honor these brave men began with a proposal by the Samuel McGowan Camp of the South Carolina Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, to the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park — which oversees the Fredericksburg, Wilderness, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania Battlefields.1 The park was established by Congress in 1927 and — unlike most battlefield parks nowadays — allowed states to place historical monuments and markers to commemorate Civil War battles provided that said monuments aligned with the park’s mission to preserve and mark significant historical sites. This legal provision was significant because since the late 20th century, Congress and the National Park Service have all but banned the erection of new monuments on American Civil War battlefields.2 Additionally, erecting new monuments generally requires Congressional oversight. I am sure the reader can see the difficulty of getting any modern Congress — even one controlled by Republicans — to approve the erection of a monument that honors Confederate soldiers. The 1927 law authorizing the creation of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County National Military Park created a specific provision allowing for states to erect monuments and markers without Congressional approval.3 It is somewhat fortunate that Congress failed to foresee the presentist backlash against the South and the Confederacy when this law was written, as the legal loophole within the 1927 law gave the necessary cover for the monument’s installment to proceed.

The monument was designed by Lee Dorn, member of the Brig. Gen. Samuel McGowan Camp 40. It was crafted by Charles Wilson of Wilson Memorials in Laurens, South Carolina. From the pictures shown below, it is evident that great care was taken as to what the monument would portray: on the front we see the crescent moon and palmetto tree — that is the emblem on South Carolina’s state flag — and an inscription listing the brigade’s five regiments (1st S.C. Infantry, 1st S.C. Rifles (“Orr’s Rifles”), 12th S.C. Infantry, 13th S.C. Infantry, and 14th S.C. Infantry) and the regiments’ commanding officers (Col. Comillus W. McCreary, Lt. Col. George McDuffie Miller, Maj. Thomas F. Clyburne, Col. Benjamin T. Brockman, and Col. Joseph N. Brown). On the back of the memorial is the above-mentioned quote. This monument is simple, effective, communicates its point, and refrains from cathartic — yet counterproductive — imagery that sometimes causes public backlash from the uneducated.

The monument cost a total of $30,000 and was entirely privately funded. Contributions included private donations from members of the South Carolina Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, and — remember this was before woke made everyone retarded — Wal-Mart Corporation. Funds were also gathered from private donations from descendants, historical enthusiasts, and other supporters. No public money went to the creation of the monument.

While there were no major legal challenges to the monument’s erection — thanks in large part to the 1927 law — there were still lengthy review and oversight processes subject to the jurisdiction of the National Park Service (NPS). Because the monument was to be installed on federal land, a mandatory review under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) was triggered. The NPS — in collaboration with state historic preservation offices in South Carolina and Virginia — reviewed the monument’s design, intended location, and its impact on the battlefield’s historical integrity. Again, the smart choices made during the monument’s design phase came back to pay dividends here; no formal legal challenge emerged, and the monument was approved at the end of the review period without delay or pushback from the NPS. There was a public comment section (which I have not been able to find and do not believe is publicly available), but the NPS indicated that the comments it received were either positive or insufficiently oppositional to stop it. It is to the credit of the men of Camp McGowan that they were able to cooperate with the NPS — ostensibly for a project with which it was not ideologically aligned — and complete the legal review without a major delay or hiccup.

The McGowan memorial was unveiled at the site of the Bloody Angle in a packed ceremony on May 9, 2009 — nearly 145 years to the day of the terrible fighting on that muddy, awful day in 1864. The event drew South Carolina state legislators (state representatives, even today, can actually be pretty based), descendants of the veterans of McGowan’s brigade, NPS service personnel, reenactors, historian Gordon Rhea, and people from the general public. Four direct descendants of General Sam McGowan also attended the ceremony.

Rhea’s speech at the monument’s dedication, describing the heroism and triumph over impossible odds that exemplified the brigade’s performance on May 12, 1864, was moving, concise, and poetic. “This monument needed to be done,” he emphasized, and anyone with any knowledge of the events of that day would have a hard time disagreeing. Rhea, to his everlasting credit, did the men of McGowan’s brigade, and the Army of Northern Virginia, the honor they deserved for their defiance on May 12, 1864. A major theme of the two-day ceremony was historical education and bringing the obscure but vital action of the South Carolinians to the attention of the broader public.

One act in particular deserves mentioning. During the ceremony, reenactors of the Palmetto Rifles — a unit consisting of several descendants of the veterans of McGowan’s brigade, including those men who died defending the Bloody Angle — received special permission from the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Park to perform a very special salute to their ancestors. For the first — and only — time in the history of the National Parks Service, direct descendants of Confederate veterans stepped into the remains of the trenches in which their ancestors fought, bled, and died. At the order “Shoulder arms!” the great-grandsons of these men raised their muskets in the direction of the tree line from which poured rank upon rank of blue-clad soldiers on May 12, 1864. When the order was given, the men fired a volley towards the tree line, just as their ancestors did time and again on that bloody day in 1864. Not since the terrible fighting of May 12 had those earthworks seen such an act. It was a poignant sight indeed, these descendants of McGowan’s soldiers, standing in the remains of the trenches in which their forefathers fought, firing one final, defiant volley in their honor and eternal glory.

All who witnessed the event could not help but shed tears. It is the author’s opinion that no higher honor could have been bestowed upon those 451 boys who never made it out of those trenches. To anyone with a knowledge of the Civil War, the Overland Campaign, and the Battle of Spotsylvania, the trenches at the Bloody Angle are sacred. They are as hallowed as the ground at Gettysburg or Antietam. The things that happened within those earthworks were unspeakable, horrific, and tragic. It is gut-wrenching to stand in front of them and know of the violence that occurred right in front of you. To stand on the exact spot on which his ancestors fought, and to honor them in such a way, is a privilege every Heritage American should wish to experience in his life. The men of the Palmetto Rifles are very fortunate, and it is to their everlasting credit that they performed the deed with the seriousness and solemnity that befitted such an occasion.

All in all, the erection of this memorial represents a clear victory of historical remembrance and preservation over presentist destruction and the “Marvel-ization” of history.

So, what can we learn from this?

The story of the McGowan memorial offers the Right a good practical blueprint for how we can engage in conscious and proactive efforts to save the history of Heritage America from the crushing and inexorable march of the modern world. Several actions taken by the men of Camp McGowan laid the groundwork for success.

First, identifying and leveraging legal and historical precedents. Using the provision in the 1927 law establishing Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County National Military Park that allowed for states to erect monuments was key. It is important to research the founding charters or laws of targeted sites (e.g., other NPS battlefields, state parks, or historic locations) to find and exploit similar provisions. While 2009 wasn’t quite as bad as today in terms of retardation concerning the Civil War, it would have probably been impossible to get Congressional approval for the monument even then. Where no legal loopholes exist, writing to local, state, and federal elected leaders can be an effective means of opening dialogue with those who may be able to advance legislation to provide a legal pathway forward. Exceptions must be ruthlessly exploited. If you know of a historical site where your intents align with the original park mission, framing a proposal as a continuation of an established tradition can also be beneficial — and it shows you know your stuff.

Second, build a coalition of supporters and stakeholders. South Carolina’s support was crucial to raising the funds and providing the legal and moral capital to complete the monument. Again, engaging with local and state leaders can be of immense benefit to bringing awareness to historical sites as well as getting the authority of government on your side. Pay attention to those who lead us who appear sympathetic to preserving Heritage America; they can be fewer and farther between the higher up you go on the political ladder, but they’re there. Private organizations can be extremely beneficial partners. Groups like the SCV, UDC, UDR, or modern equivalents such as local or state historical societies can provide manpower, expertise, and grassroots momentum.4

Third, secure private funding. When the government basically hates white Americans and is trying to replace us with compliant foreigners, public resources for preserving this nation’s history may be hard to attain (but I’ll be damned if Rajesh from Calcutta doesn’t get his welfare check!). The cost of the McGowan memorial came entirely from private funds and donations. Crowdfunding our heritage will likely be the most effective means to raise the necessary funds to preserve it. Framing efforts at historical preservation as an attempt to build community goodwill will likely receive enthusiastic support from locals who have ties to the area. Americans generally like to help out a noble cause, and more and more Heritage Americans understand that preserving and memorializing their history is the noblest of causes. In contrast to private funds, public funding also comes with bureaucratic hurdles, red tape, resistance, and potential backlash. Don’t put a target on your back if you can help it.

Fourth, partner with authorities. It is almost a certainty that some authority, whether it be a local, state, or federal entity, is going to have to sign off on any historical preservation project that is attempted. Partner with them. Befriend them. Build relationships with them. Prepare detailed proposals justifying historical significance, back it up with support from historians, and mobilize supporters to take control of public input/comments phases in a review process. The NPS’s goodwill and good relationships with the men of Camp McGowan doubtlessly allowed the McGowan memorial to complete the review process with no major hurdles. Always remember, you’ve got the same goal as these organizations. You want to preserve history — in theory, so should they.

Fifth, craft a compelling narrative. History is a collection of stories. It is not facts and statistics, dates and names, but a living, breathing past. Whether it is the actions of a unit on a battlefield or one man in your town’s local legends, find a compelling story that matters to you, and see to it that it is memorialized. You do your people great honor when you commit their words and their deeds to permanent memory, and that honor is something no hostile force can ever take from you. Whether it is the action of one man or many, find that story that matters to you and endeavor to have it cast in stone and granite.

Sixth, anticipate opposition. In a more civilized age, the idea of ripping down monuments would be seen as the barbaric and ghoulish act that it is. Sadly, we live in an age where evil is the law of the land and the will of our rulers more often than not. Preempt criticism by framing historical preservation efforts as just that: preserving history, not making a political statement. If you can afford it, consult with legal counsel and be ready for challenges. Cultivate ongoing local support and take advantage of such things as easements, and secure deeds to preempt and resist future attempts to tear down what you have memorialized.

With these points of advice — all gleaned from the story of the McGowan memorial’s erection — I hope I have left you with some small idea of what you can do to help preserve American history in this vile, anti-American age in which we find ourselves. The process by which the men of Camp McGowan endeavored to honor their ancestors and kin is a blueprint for the Right and for Heritage America to plant lasting symbols of our historical narrative and vision in the public square. To quote Pete Quiñones, “We’re in the education phase.” I for one look forward to pushing back against those who would demean the accomplishments of my forefathers for the false god of modern sensibilities and hope over the course of my life to offer the most spirited and successful defense of their memory that I can.

This article would not have been possible without the help of Robert Roper, former Commander of the South Carolina Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans. It is the author’s hope that this article does him, the men of Camp 40, and the soldiers of Sam McGowan’s Brigade the honor that they all deserve. Deo Vindice.

Thumbnail image: The Bloody Angle by Mort Künstler.

It is estimated that nearly 110,000 (one in six) of the American Civil War’s battle casualties occurred on the battlefields of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County National Military Park. No other place in America more vividly reflects the War’s carnage than this hallowed ground.

This is not entirely without reason or malice, as new monuments alter the landscape of the battlefield (see the stone wall at Gettysburg for what this looks like), and the struggle to preserve these battlefields has been difficult enough.

This was primarily due to the nature of the battlefields in the park as well as the park’s size and scope, the spirit of reconciliation that permeated our politics in the early 1900s, and lobbying from still-living Civil War veterans who wanted to memorialize their fallen comrades before they passed away from old age.

On that note, these organizations are always desperate for new, young blood and fresh ideas. If you’ve got the time and the desire, consider joining a local historical group and see what they have to offer.

I’d love to see this being done more out here in California (specifically in my area in Southern California). I’m not from California, but it’s the state that’s taken me in, and out of my gratitude for her I want to make sure the best of her is preserved.