I delivered the following presentation on the evening of Friday, June 7, at this year’s Old Glory Club Conference.

Introduction

I’d like to start with a vaguely remembered missionary story that my mother probably shared with me.

As has often happened in recent times, everyone in a Muslim village in the middle of nowhere woke up one morning having all had a vision of Jesus after which they became Christians en masse. Later it was found that a Christian missionary had been martyred in this very village hundreds of years before.

In Genesis, the Lord says to Cain, “The voice of your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground” (4:10).

I believe, and have experienced, that a place, the ground we stand on, has a memory. I had a particularly haunting experience I will never forget when I visited Little Bighorn Battlefield, the site of Custer’s Last Stand.

Not only ground but peoples have characters that persist. Neema Parvini points out that, for example, Iran somehow remained Iran even after being conquered by Muslims. They made their own version of Islam, they still speak Farsi, etc. In short, they’re still Iranians.

The scriptures say:

Thus says the Lord:

“Stand by the roads, and look,

and ask for the ancient paths,

where the good way is; and walk in it,

and find rest for your souls.

But they said, ‘We will not walk in it.’”(Jeremiah 6:16)

I’m going to give you a spoiler right now and tell you where I’m going with this talk: To understand and prepare for a post-Imperial America, we should learn about what came before Imperial America, and we should focus specifically on our local area. We all would glibly say that globalist homogenization is a doomed project. But do we really believe it? Do we live it? Do we, even now, look beyond it and recognize that peoples and places have a continuity in the long run?

While the future of the political entity “the” United States somehow feels uncertain these days, the American people have been here long before 1898, the formal beginning of overseas empire, even before 1776, and we will be here long after. Our pre-Imperial history as Europeans in North America is over twice as long as this time since 1898. If you include when Catholic Europeans established a presence in the New World, then that is 400 years of Europeans here before the beginning of U.S. Empire. This era will pass, and our descendants will still be here, so we work together with our posterity in mind.

Before I get to all that, though, there is something in our way. I’m going to spend a good chunk of this talk removing this obstacle that, I believe, holds us back from looking into our past.

In fact, I didn’t realize how much it was holding me back subconsciously until doing the research for this talk.

The Allegation

Here is the charge against our ancestors. I quote from a student who passionately laid it out to her professor a few years ago:

America was and continues to be located on stolen lands. This land was forged in genocidal conditions to eliminate Native Americans from the continent… we lived on their stolen land without their permission… we have yet to admit that genocidal policies neutralized any possibility for an ethical space. The United States of America, she declared, was irrevocably tainted as a country. No American could claim to ever have a legitimate ethical identity short of giving back stolen lands to the Native Indians; or, paying them for all illegally acquired lands.

(p. XIII, Not Stolen)

This student was voicing the latest version of a campaign that has been going on my whole life. It is now called “Settler Colonialism,” and it frames our history in Marxist oppressor/oppressed terms.

I will be drawing throughout here from the book Not Stolen: The Truth About European Colonialism in the New World by Jeff Fynn-Paul. Thanks very much to Wanjiru Njoya at the Mises Institute for recommending this book.

Fynn-Paul writes:

The idea of settler colonialism was popularized by… Australian academic Patrick Wolfe, whose book Settler Colonialism was published in 1999… According to the doctrine of settler colonialism, Europeans who came to the New World, and to other areas such as Australia and New Zealand, engaged in a particularly egregious form of colonialism. For them, it has been alleged, the goal of colonization was not simply to dominate a subject people politically, culturally, and economically. In addition, it was infused with a racially motivated drive to replace or exterminate the Indigenous inhabitants altogether.

(p. 98, Not Stolen)

In short, millions were murdered. Probably tens of millions.

The Plea

I am not going to enter a plea of “Not guilty” to this indictment.

Instead, I’m going to go full denialist and plea: “It didn’t even happen.”

There are two main points I want you to remember in response to this charge of genocide.

First, adapting the phrase from David Starkey that got him canceled, there could not have been a genocide because there are so many damn Indians still around.

Second, so that they can pump up the genocide numbers, they claim there were more Indians here in 1491 than is remotely plausible. Tricky, tricky!

Though I’m going to be knocking down a lot of lies here, let me be clear what I’m not doing: I will not whitewash our history and pretend that Europeans always acted as angels. They did not, and episodes like the Trail of Tears are just plain bad and unjust.

But neither should we accept this narrative of our ancestors as demons who, from the moment they stepped foot in the New World, were saying, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian,” and merrily slaughtering their way across the continent. That story is just a lie.

How Many Indians Were There in 1491?

To give you a flavor of the cunning trick I mentioned above, listen to this. David Stannard, in his book American Holocaust, claimed: “What happened on Hispaniola was the equivalent of fifty Hiroshimas.”

Stannard is referring to one of the islands that Christopher Columbus found on his first voyage and on which he established a colony immediately. Hispaniola today hosts the nations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

To produce a genocide narrative, the 1491 population of Hispaniola is claimed to be as high as 7 million. A USG-funded website Native Voices states:

AD 1493: Christopher Columbus, who needs to demonstrate the wealth of the New World after finding no gold, loads his ship with enslaved Taíno people. During the next four decades, slavery contributes to the deaths of 7 million Taíno. By 1535, the Taíno culture on Hispaniola is gone.

(p. 31, Not Stolen)

Now the Taíno had no written records, so what can we say about this huge population claim?

As an engineer, I really love how Fynn-Paul comes at this using a technique I learned as “back-of-the-envelope calculations.” Despite using it throughout my career, it feels like a magic trick.

So, we don’t have 1491 population numbers for Hispaniola. But what do we have? Well, we know how big Hispaniola is. It’s “just over one half the size of England excluding Wales and Scotland.”

And we do know something about the population of England about that time, which is well studied. “Our best guess is that England in 1500 had only 2.1 million people, living on double the area of Hispaniola.” So, our first sanity check: “If Hispaniola really had seven million people in 1491, that would make its population roughly triple that of England at the time, and its population density about six times higher” (p. 32, Not Stolen).

We have reasons to doubt these numbers.

“England by 1500 had one of the most advanced agricultural regimes on Earth, with widespread use of heavy ploughs and draft animals.”

“Meanwhile, the natives of Hispaniola were using stone tools and practiced a light form of hoe and mound farming in clearings. They grew very limited crops, ate little and conserved energy to make up for their poor diet, and employed no animal power or mills.”

Furthermore, “England was almost entirely cleared of forests, and a significant portion of its land was either farmed or used for grazing.”

While on Hispaniola, “owing to their lack of metal axes their island was heavily forested; coupled with the mountainous terrain, this means that only a small percentage was arable.”

So a much more reasonable estimate is that the population of Hispaniola was more like 200,000. “Disease, flight, and mistreatment — in that order” did reduce the population to around 90,000 in the 1510s (p. 32, Not Stolen).

So this would deflate Stannard’s claims of “fifty Hiroshimas” down to less than a single atom bomb, and that is if we lay moral blame on the Europeans for things like disease, which they did not intend and, in fact, often fought when they had means to do so.

Similar exaggerated population sizes are made up for the New World overall, one popular claim being that the New World had more people than Europe in 1491. I won’t step through the back-of-the-envelope calculations again, but suffice it to say that “according to demographers, the New World contained only about 10 percent of the global population of four hundred and fifty million people in 1491, while the other 90 percent lived in Africa, Europe, and especially Asia” (p. 35, Not Stolen).

Given that the New World is about half the area of the Old World, why the big difference in population estimates?

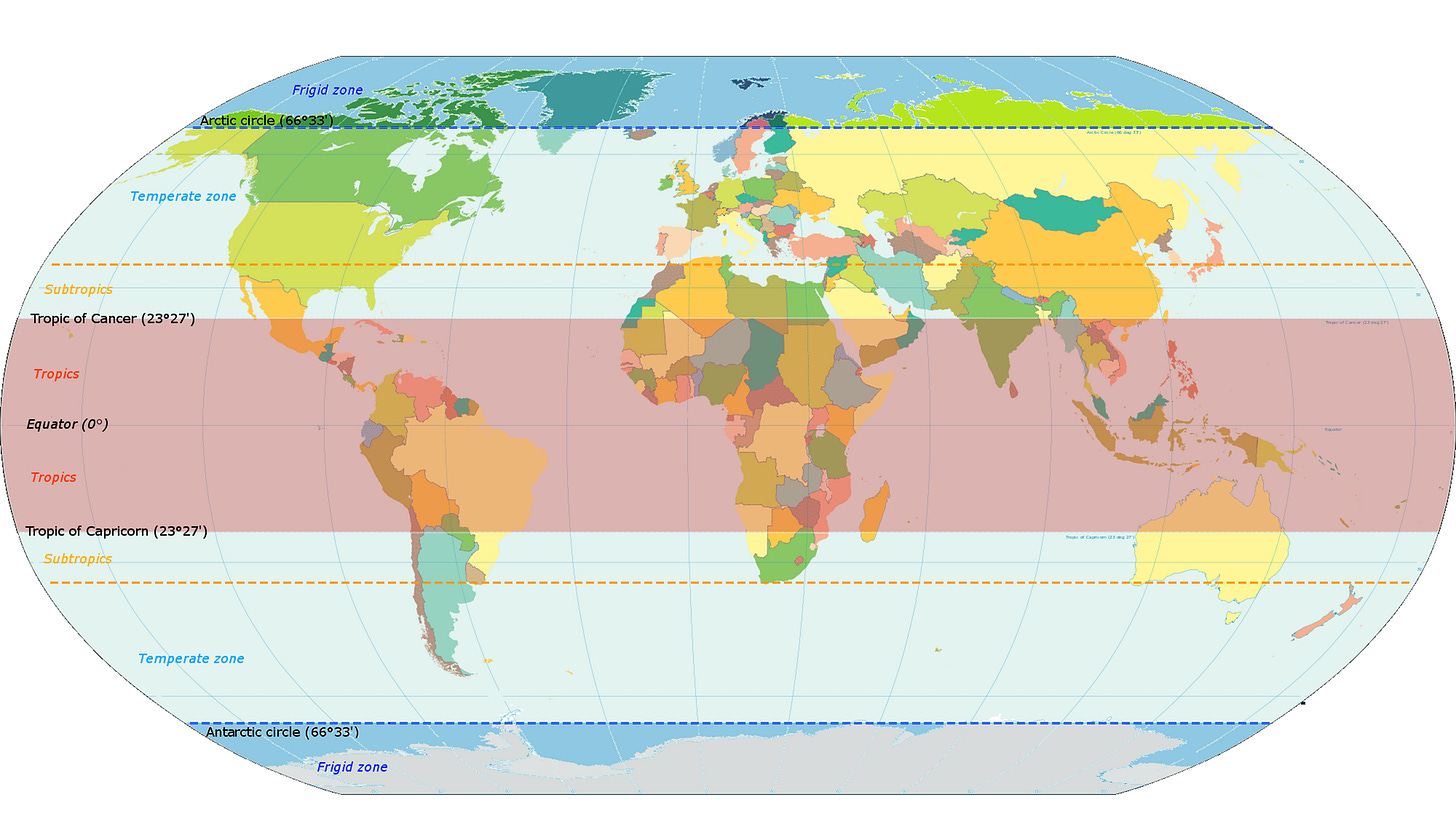

In the premodern world, people could only live where there were abundant food supplies. The major Old World civilizations evolved under [ice-free] conditions, in semitropical and temperate regions such as the Nile Valley, Mesopotamia, and in the Indus and Yellow River valleys.

…

Unfortunately for the New World peoples, the area that was ice-free year-round was relatively small. Fully one-third of the New World land is locked up in Canada, Alaska, and Greenland — which were far too cold to support large populations. Most of the continental United States freezes pretty hard in the winters, and the world was in the grip of a Little Ice Age when Columbus arrived. Most of northern Mexico is desert. Central America and equatorial South America are mostly thick, impenetrable jungle. At the southern tip of the New World, Argentina and Chile also get cold in the winters. This leaves only a narrow territory at the edge of the rain forests in central Mexico and analogous territory in parts of the Andes Mountains, where conditions were right for the multiplication of premodern peoples.

(p. 35, Not Stolen)

So where were the major populations of Indians in 1491?

[C]lose to 80 percent of the New World population was located in two very localized regions: central Mexico and the northern Andes. The rest of the New World was thinly populated indeed, with all of North America north of the Rio Grande probably containing between one and three million people. Most of these were spread across the Mississippi, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions, with few settled in the west and north, apart from a few Pacific coastal regions including California. Population densities in most of this area were usually less than one person per ten square kilometers.

(p. 36, Not Stolen)

For comparison, “England had about ten people per square kilometer in 1500, which is a population density fully one hundred times higher than most of North America at the time” (p. 36, Not Stolen).

Particular to where I live, I’ll just briefly mention: “The Mississippian culture, one of the most advanced pre-Columbian civilizations in the continental U.S., evolved along the shores of this river system. When the Spanish under De Soto arrived in the area in 1541, this proto-civilization was at a low ebb. The maximum population supported by some of its cities was a few hundred people” (p. 36, Not Stolen).

Once we understand where the Indians were, then look around at where Indians are today, then we can see the relevance of the Starkey point. There are still so many damn Indians around… Exactly where they were when Europeans arrived. In fact, compared to those times, we see a growth of Indian population in places distant from the warm zone where large numbers had not been able to survive before Europeans arrived.

By the way, the current Total Fertility Rate of American Indians is just slightly under that of non-Hispanic whites. And that would not count the many descendants of Indians who do not identify as Indians because of interbreeding. Like our own paleface member of the Kaw tribe, Ryan Turnipseed.

Here indeed is the blood guilt we may have as Europeans in North America:

Credible experts have calculated that the total number of North American Indians who were massacred during the entire five-hundred-year history of European colonization is less than ten thousand individuals, maximally twenty thousand… This is out of a population initially numbered at more than one million. Very likely, more Europeans were massacred by Indians during the settlement period than the other way around… Certainly far more than ten thousand Indians were massacred by other Indians in North America during this same time period, though next to no attention is paid to this fact by modern historians.

(p. 113, Not Stolen)

To wrap up the genocide denial argument, I’ll let Fynn-Paul state the “so many damn Indians” point more formally: “The Americas today are simply teeming with the descendants of the Indigenous people who were alive in 1491… Europeans remain a minority in every country that had a dense settlement of Indigenous people in 1491” (p. 41, Not Stolen).

In fact, “the U.S. Indian population has remained steady proportional to the overall U.S. population since 1810, despite massive immigration from Europe in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” (p. 253, Not Stolen).

We Europeans did not genocide the native Americans.

Was America Stolen?

So, if Indians weren’t mass-murdered by Europeans, wasn’t America nonetheless stolen from the Indians by Europeans?

The answer is, mostly no… Except for the Trail of Tears period, which we’ll come back to.

The first thing to understand is that there were hundreds of years where violence was occasional but not the norm:

Except during times of war, Indians and colonists traded, taught, relaxed, exchanged knowledge, and built friendships with one another. Men like John Smith sometimes spent months at a time living with the Indians, while bands of Indians might camp for several weeks in the vicinity of Jamestown. The same patterns are found in early Quebec and Massachusetts.

(p. 231, Not Stolen)

Fynn-Paul quotes at length from historian David L. Preston’s book The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667–1783. Preston’s description of his project brings home that it is quite reductionistic merely to describe interactions between Europeans and Indians as only that between oppressor and oppressed:

My purpose in writing this book is to help readers understand the texture of human contact among ordinary European and Indian frontier settlers whose everyday lives were profoundly interwoven… The details of the tapestry can be gleaned from a host of meetings, scenes, places, and conversations described in eighteenth-century records: three French-Canadian sisters who lived among Catholic Iroquois for over two decades and operated a trading store in their village; Indians wandering the streets of colonial Montreal and drinking beer at Crespeau’s tavern; German immigrants who approached Mohawks for permission to settle among them; Christian Mohawks who insisted that they would live out their lives as brothers with German Christians, who baptized and christened their children and were married in German churches; Indians who reveled with white settlers on Christmas Day; Scots-Irish squatters who lived peaceably with Indians and paid yearly rents to Indian landlords, in defiance of Colonial landlords; Scots-Irish frontiersmen enjoying a friendly drink with Iroquois warriors at a backwoods Pennsylvania tavern; an Indian playing European tunes on his fiddle in a Mohawk Valley tavern; a Mohawk Indian with a European wife who lived among British frontier settlers in the Ohio Valley; a Palatine settler who refused to share a meal with an Iroquois in his home and pushed him away from the hearth; Palatine farmers in New York who made wampum belts, spoke Iroquoian languages, and negotiated with the French in Canada; a hatchet cleaving the skull of a Swiss settler, attacked at his frontier farm by English-speaking Delaware Indians with English names; a Scots settler murdered on an Ohio Valley farm while harvesting wheat with a man whose mother was a Delaware Indian, his father an Englishman.

(pp. 231–233, Not Stolen; pp. 2–4, Texture of Contact)

Keeping the whole timeline of Europeans in the New World in mind is very important context for understanding the population shifts in North America: “[F]or most of the five hundred years since Columbus, over 90 percent of North America belonged to the Indians. In the early 1800s, fully three hundred years after Columbus discovered America, Europeans still inhabited only a fringe of the North American landmass” (p. 240, Not Stolen).

The critical period of land transfer from Indian to U.S. ownership is 1830 to 1880. However: “No generation since the 1890s has stolen land from the Native Americans in a significant way, and no single American generation before 1830 stole more than a tiny fraction of North America from the Native Americans” (p. 240, Not Stolen). That is, only two generations out of twenty generations of Europeans bear significant blame.

Part of what happened in the first few hundred years is that Europeans would want to spread slightly farther inland from the East Coast. Indians would sell land they hunted on to Europeans who were going to farm it because Indians figured out how to profit from land markets. Then the semi-nomadic Indians would just move their hunting a little bit west. Prior to the 19th century, this was a very gradual process.

There was generally respect for Indian territorial sovereignty: “The French and British treated Indian polities such as the Iroquois confederation as sovereign powers whose boundaries were to be respected” (p. 24, Not Stolen). After the U.S. was formed, early American Presidents took the same attitude. George Washington, for example, “became increasingly protective of Indian welfare, and as president he put a great deal of energy into protecting Indian land from white encroachment” (p. 259, Not Stolen).

So what happened? North American Indian tribes killed each other quite a bit. Others assimilated. Therefore, there was a dwindling population between 1600 and 1800:

This left the land between the Appalachians and the Mississippi practically vacant by the time Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. By 1810, the entire Iroquois nation probably amounted to some ten thousand individuals. These inhabited an area encompassing more than eight modern U.S. states along the southern Great Lakes, with large swaths of modern-day Ontario in Canada thrown in.

(p. 252, Not Stolen)

There is a problem with considering 10,000 people to own such a huge amount of land. I can declare myself King of the Moon. In fact, I have. But in what notion of justice am I the owner of the Moon, which I am not mixing my labor with?

Nonetheless, it seems clear to me that President Andrew Jackson was conducting a legal “smash and grab” when he kicked the southern tribes out of their homes and off their land. Even here, where I think there is true injustice (for which President Obama compensated Indian tribes with several billion dollars), there is some critical context. These tribes amounted to about 70,000 individuals. Meanwhile, the European population was growing rapidly during the period before this expulsion — primarily through natural increase, not immigration, by the way. By 1820, the European population was nearly 10 million:

While the Indian population east of the Mississippi actually began to grow somewhat during this time — in part because of the robust Indian-protection policies of the U.S. government — the Indians nonetheless remained hopelessly outnumbered by a factor of one hundred to one.

(p. 253, Not Stolen)

Why was the Amerindian population east of the Mississippi so small by 1800?

First was the inefficiency of hunting and gathering. Second was Amerindian susceptibility to disease. Third was Amerindian aggression by the likes of the Iroquois, which reshaped Amerindian society from within, and made population replacement difficult. Fourth was gradual assimilation into farming society.

(p. 254, Not Stolen)

An important conclusion from all this is that “land in the colonial and early American periods was ‘not stolen’ in the sense that most Left-wing historians and pro-Indigenous activists would have us believe” (p. 256, Not Stolen).

In learning what I’ve just presented to you, and much more, I could feel a barrier being removed inside me to looking back at our history. Learning this more balanced history, I find it much easier to relate to our ancestors. They weren’t the incomprehensibly demonic killers that we’ve been presented. There were, of course, some crooks and swindlers. But mostly they were fair-dealing and brave builders, not pillagers.

But I have also undergone a shift in what kind of history I’m interested in as I look back…

Learning My Ground

When I first got interested in politics, it was during the Cold War. It’s taken me a while to find it interesting to learn about my local area. In fact, I’ve already been doing it without being as conscious about it as I’m suggesting here. This has been so unconscious that I realized that the perfect ending to this talk is something I wrote over a year ago for the Old Glory Club. Some of the things I’ve been learning came together in telling that mostly forgotten story.

So, some things I have learned about my local area:

Renaming

I’ve learned that our current era isn’t the first time that there was a bit of renaming due to the politics of the day.

During World War I, a number of German names were replaced in St. Louis. Decades ago, I learned from old Mr. Krummenacher that the street I lived on at the time had originally had a German name, though I don’t remember what it was now. But I found that in 1918, a number of streets were renamed in St. Louis. Hapsburger Avenue was renamed to Cecil Place, Berlin Avenue to Pershing Avenue, and Knapstein Place to Providence Place.

Hermann

Speaking of Germans in my area, I’ve really enjoyed visiting the German areas of Missouri like Hermann that retain a distinctive German character. They grow wine in this part of Missouri, and I just marvel at how orderly their farms are.

I particularly find amusing the 24/7 meat vending machines in Hermann where you can get some emergency bratwurst at 3 in the morning.

I’ve leaned into the German aspect of our area a bit because my wife’s maiden name is characteristically German and both of her grandfathers spoke German to her. So this is part of our children’s heritage, even if it is not part of mine (which is purely English and Scottish).

Black Communities

I have a Nation of Islam friend who I talk to regularly at the Jewish Community Center where I work out. I feel like this is the start of a joke: “A black Muslim and a far-right white guy were talking at the Jewish Community Center…”

He has been teaching me about the informal functioning of black communities in Southeast Missouri and how these communities were destroyed by the welfare state and other aspects of our age. What makes his experience particularly interesting is that he’s old enough to have actually grown up in that community when he was young and watched the dissolution of the community over the course of his lifetime.

Cahokia Mounds

My family occasionally visits Cahokia Mounds. These are remnants of that Mississippian civilization I mentioned earlier. They have some artifacts they’ve found in the museum. But mostly we like to climb to the top of the largest of the mounds, stand on that mound where the Mississippians once lived, and look back at St. Louis from that high vantage point.

Geology of Missouri

Due to our membership in the St. Louis Mineral and Gem Society, I have been on regular field trips to go rock-hunting around the state.

I’ve learned that Missouri is a particularly nice place to be for geologists and rock hounds because there are so many different kinds of geology to see, starting with St. Louis itself and then going through different strata as you go south.

I already knew about the numerous caves in Missouri from caving when I was young. Speaking of which…

Bonne Terre Lead Mine

A particular pleasure was touring the abandoned Bonne Terre Lead Mine. After they stopped digging deeper in the 150-year-old mine and turned off the pumps in 1962, it filled up and created a billion-gallon underground lake.

We took the boat tour, where you can look down in the clear cave water and see abandoned mine equipment.

They do scuba diving there as well.

I have to mention that this is the only place in the U.S. where you can just look up at the ceiling and see a fault line, in this case the New Madrid Fault.

The Fate of the French in Missouri

Having been surrounded by French place names all my life in St. Louis, I finally wondered recently what happened to the French. I didn’t remember any great historical event that caused them to leave.

I finally figured out that they never left; their descendants are all around me.

Paw-Paw French

I learned that in parts of Missouri and across the Mississippi in Illinois, a dialect of French developed nicknamed Paw-Paw French. It is one of the major varieties of French that developed in America.

At one point it was widely spoken in areas of Bonne Terre, Valles Mines, Ste. Genevieve, Old Mines, St. Louis, Cahokia, and other areas. It has nearly died out at this point.

Ste. Genevieve

My wife lived in an old town called Ste. Genevieve for a summer when she was single.

This is a community that very much remembers its French roots and has preserved many French buildings from hundreds of years ago.

We have gone as a family to their annual celebration of Jour De Fete.

Old Mines

On another geology trip, I met a farmer in the Old Mines area. I gave him what Charlemagne calls “the RadLib grilling” and found out that his grandmother spoke French. He told me how she would swear at his grandfather in a stream of French which he didn’t understand… But he got the idea.

We were collecting rocks on this man’s land from an old lead mine which was dug out with rather primitive methods a couple hundred years ago. The “mine” just looked like a big hill with a depression in the middle, sort of like a meteor strike… Except that the hill was from them chucking out rocks from the hole they were digging.

The Battle of St. Louis

So here is a story I stumbled on that weaves together some of this local knowledge I’ve been gaining.

On a visit to the first settlement west of the Mississippi, Ste. Genevieve, I was surprised to find out that they had played a critical role in saving my city from being taken by the British.

The surprise was not just the important role of what is now a much smaller town in defending St. Louis, but that I had never heard of the battle at all!

Why had I never heard of this before?

Though it was a battle with huge implications, it was not relevant to the origin story of America happening to the east. This battle has been forgotten in part because it happened in 1780, during the American War for Independence.

Not only that, but no Colonial seceding from Britain was involved with this battle at all (although Colonials were involved with a simultaneous battle in nearby Cahokia).

The Battle of St. Louis, also called the Battle of Fort San Carlos, was a battle with British-led Indians on one side and French settlers led by Spanish military on the other.

Also, the St. Louis of 1780 was not the large city I grew up in. It was only a village at the time, having been founded just fourteen years before.

Yet the British saw taking St. Louis as the first step in an ambitious campaign. This village was on the west side of the Mississippi River and would be a strategic base for gaining control of the Mississippi Valley.

With no British troops available, the British commander enticed Loyalist trappers to recruit Indians for an attack on St. Louis with an offer of control of the fur trade in upper Spanish Louisiana.

The attacking force eventually consisted of two dozen fur traders and about 1,000 Indians. The largest contingent were Sioux, but there were also Chippewa, Menominee, Winnebago, Sauk, Fox, and smaller numbers from other nations.

St. Louis only had about 200 men, mostly inexperienced militia. Only 29 were Spanish military. Also, in March 1780, there were no defenses.

St. Louis was destined to fall to British control, except for two things.

First, word got to the Spanish months before the attack. The commander asked for donations from the townspeople as well as using his private funds to build a tower, Fort San Carlos, to defend the village with cannon. With only enough time to build the one tower, they dug trenches connecting the tower to the Mississippi River so that the village was defended on all sides.

Secondly, an appeal to François Vallé at the French Colonial Valles Mines yielded critical help.

Not only did he send his two sons and 60 well-trained militia from Ste. Genevieve, but he also sent genuine lead musket and cannon balls from his lead mine. This was a huge advantage over the limestone pebbles they would have otherwise been using. Lead is fifteen times heavier than limestone.

Even so, when the attack came on May 26, 1780, every man was critical. If men were drawn out from the defenses, then the Indians could pour their larger force against the weak point.

And this brings me to the other, horrible surprise about this event. A horror that had the men begging to leave their trenches during the battle, for the Indians used torture as a tactical weapon.

Some of the villagers had been caught outside the city’s defenses when the attack came. When the Indians found the city well defended, they started torturing those they captured so that their screams would draw out the defenders.

The Spanish commander, Lieutenant Governor Fernando de Leyba, refused to let the defenders make a sortie to stop the torture.

Eventually the screams stopped and the Indians departed, destroying and burning as they went.

An attack on nearby Cahokia, just east of St. Louis and home to the Cahokia Mounds, was easily defended by George Rogers Clark and other Colonials.

Routed at both St. Louis and Cahokia, the British never again tried to control the Mississippi Valley, leaving it in the hands of the Spanish, which allowed it to be purchased by these United States under President Thomas Jefferson twenty-three years later.

Some battles involve hundreds of thousands, with tens of thousands of casualties, and don’t change a thing.

Some battles involve mere hundreds, but change the course of history for half a continent.

Hail to the defenders of St. Louis!

Conclusion

Dig in where you are.

Know your ground.

Bibliography

Puritan’s Empire by Charles A. Coulombe

Not Stolen by Jeff Fynn-Paul

Conceived in Liberty by Murray N. Rothbard

Albion’s Seed by David Hackett Fischer

Cronyism: Liberty versus Power in Early America, 1607–1849 by Patrick Newman

America’s British Culture by Russell Kirk

“The United States Is a Colonial Empire, and an Extremely Successful One” by Ryan McMaken