French Calvinists, Spanish Catholics, and Florida Indians

The Role of Religion in the Colonization of Florida

By guest author Matthew Pearson.

The colonization of Florida by the Europeans was a fantastic feat. Enchanted by the New World and ready for riches, many embarked on voyages they knew would likely lead to their demise. But with courage and vital spirit these men ventured into the unknown, ready to make a name for themselves and receive glory in their memory. While gold and glory were key reasons for these expeditions, another factor was at play: religion.

In the early modern world, religion was something which permeated every aspect of life. Gold and glory drove many to the New World, but so did the glory of God. There was not only a whole new world to be discovered, but a whole new world to be Christianized. Savage Indians with minds darkened by sin could finally be illuminated by the light of the gospel! With high religiosity came much conflict in early modern Europe. The cataclysmic impact of the Reformation led to a dividing up of Western Christendom, with warring factions always at play both polemically and on the battlefield. These conflicts did not stay in Europe, but traveled to the New World — especially to Florida, as seen in the conflict between French Calvinists and Spanish Catholics. In this article, I wish to tell the story of religious conflict in the 16th-century colonization of Florida and how this conflict influenced relations with the Florida Indians.

Before vacationing to the sunny beaches of Florida, it is important to take a detour to 16th-century Western Europe. The Reformation was arguably the most paradigm-shifting event to happen to Western Europe during this time. To Protestants, the bonds of papal tyranny had finally been broken, and the freedom of the gospel was able to go forth. To Catholics, a new heretical sect backed by various magistrates was a powerful threat in great opposition to Christ’s Church. Though France and Spain remained Roman Catholic, it was France, the homeland of reformer John Calvin, which the Reformation had breached internally.

Many orderly Frenchmen were quite impressed with the publication in 1539 of the second edition of John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion and felt as though it offered an ordered system which they perceived to be lacking in the Roman Church of their time. Those Frenchmen who adhered to Calvinism came to be known as the Huguenots, and their French Calvinism seeped into all classes of society, even making its way into the courts of France.1 French Catholics were infuriated by this and went to every extent to stop the spread of Calvinism.2 Despite having gained much prominence in France, after the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis of 1559, the Huguenots fell out of any political favor due to their displacement by the Catholic House of Guise. This treaty had also given Spain the right to plunder in the New World.3 Despite this, French Calvinists would decide to embark on a voyage to Florida.

Upon French arrival in Florida, the Spanish naturally had an intense reaction. This reaction was rooted in a sense of both physical and spiritual entitlement to the Western lands. In July 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas had moved the Line of Demarcation to a longitude 340 leagues west of Cape Verde, thereby granting Portugal all the lands discovered to the east. Yet it was all of North America which lay west of the line in Spanish territory. With this in mind, Spain felt that the pope’s spiritual grant combined with this treaty ensured a title to all the land regardless of who lived there.

Despite Spain’s confidence, the English, Dutch, and French disputed this claim by their application of res nullius, which they believed proved that only physical possession of territory was a factor in owning newly discovered lands.4 European powers were kept outside of this hemisphere not because of agreement with Spain but because of Spanish force.5 Spanish claims to land were thoroughly political while also rooted in a sense of spiritual entitlement. Like that of the Spanish, the French interest in the land was political and religious. The Huguenots, having fallen out of favor in France, settled Florida with a primary goal of escaping religious persecution.6 On top of this, the tropical land was seen as a second Canaan, rumored to flow with milk and honey, abounding in timber, vines, olive trees, Indians, pearls, and maybe even silver and gold!7 For the French, Florida was not merely a land to plunder and abandon, but one to settle and establish roots in, a tropical Calvinist Jerusalem!8

The initial Spanish efforts to establish colonies in Florida were unsuccessful. The first attempt at planting a colony in Florida was by Spanish mariner Juan Ponce de León, who landed along the Florida east coast, where one today can visit Melbourne Beach. While the Indians were initially friendly to the Spaniards, they began to resent them once the Spaniards attempted to conquer them. The Indians successfully resisted, remaining unconverted to Catholicism, while de León, wounded by an arrow, was forced to retire to Cuba, where he would eventually die.

In the record of Spanish attempts at colonizing Florida, it was common for the Spanish to deceive the Indians through trickery, thus engendering a distrust of the Spanish among the Indians.9 The relationship between the Indians and French Huguenots differed substantially. Led by Jean Ribault, the Huguenots, upon arrival near what is now known as St. Augustine, were successful in both winning and retaining a relationship with the Indians, thereby enabling the French to establish the short-lived Port Royal Colony.

Two years later, another group of Huguenots arrived, led by René de Laudonnière, who established the Fort Caroline Colony on the St. Johns.10 Even though in the long term it was the Spanish who remained in Florida, having rooted the French out and committed to the conversion of the Indians to Catholicism, the impact of the Huguenots’ relationship with the Indians was significant. During their brief stay of one year and three months, the French were able to gather more information on the Timucua Indians, one of the more prominent Indian groups in Florida, than the Spanish had from their entire two and a half centuries of occupation.11

Any well-sustained future European interaction with the Timucua Indians was made possible only by the short-lived Huguenot colonies. Despite the more positive relational developments between the French and Florida Indians, this relationship was not perfect.

Both Ribault and Laudonnière understood the importance of maintaining good relations with the Timucuas, but alliances were still difficult to maintain. Laudonnière and Ribault had established a friendship with a chief in the eastern Timucua named Saturiwa. Later the French also established a relationship with Outina, a rival chief of Saturiwa. The newly established alliance with Outina ended the previous relationship with Saturiwa and led to serious consequences. When the Spaniards began to drive the French out of Florida, those under Saturiwa provided support for the Spanish, holding no sympathy for the two-faced Huguenots intruding on their tropics.12

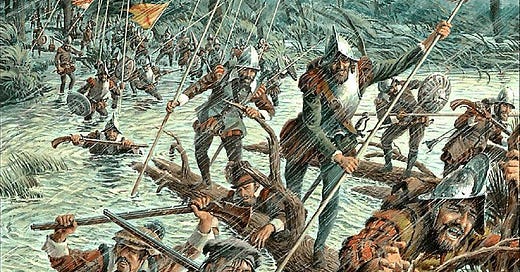

The French met a grizzly end in Florida in 1565. Both colonies established were already near starvation, and the arrival of the Spanish, led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, sealed the fate of these famished colonies.13 Menéndez was an avid Roman Catholic, committed to ridding the New World of all Protestants, willing to fund the expedition to Florida himself if it meant ridding the area of these pests enticed by the heresies of Luther and Calvin.14 Upon arrival, Menéndez led a group of 500 soldiers to attack an unguarded Fort Caroline while many were asleep in bed. Within an hour, the Spanish flag flew over the fort, and 132 men lay dead at the hands of the Spaniards. Women and children under fifteen were spared only because Menéndez feared God’s judgment if he acted too cruelly.15

Two French ships escaped, one to France, piloted by Ribault’s son, and the other to England, bearing Laudonnière. Even after taking Fort Caroline, numerous massacres with death tolls reaching the hundreds were carried out by Menéndez and his men against the Huguenots.16 Finally, Ribault’s life came to an end when he was murdered by Menéndez’s brother-in-law and a Spanish officer, leading Menéndez to rejoice, for if allowed to live, “he [Ribault] would do more in one year than any other in ten.”17

Upon the driving out of the French, under Menéndez the settlement of St. Augustine was established. From this point on, the Franciscans began toiling among the Indians immediately for the sake of converting them to Catholicism. While initially stubborn, the Spaniards continued to evangelize and to build chapels.18 Even nearly a hundred years after colonization, the Spanish still sought to keep the Indians in check by making sure that their activities were thoroughly Christian, going so far as to ban a common cultural ballgame which they thought to be too barbaric and pagan.19 The Spaniards were eager and determined to root out paganism from the Indians so that they could fully embrace Christ.20 Though the Spanish were more evangelistic than the French, it is also important to note the difference in time settled as well as the methods of building relationships. As noted earlier, the French, despite some faults, were able to build fruitful relationships with the Florida Indians. To evangelize them immediately would likely have severed these newly formed relationships and foiled any further opportunities for proselytizing. Had the French stayed put longer in their colonies, evangelization would have taken place to establish an equatorial Calvinist establishment.

Thus ends the Protestant-Catholic conflict in the colonization of Florida. The Spanish Catholics had triumphed over the French Calvinists. The Spanish held on to Florida until 1821, when it was ceded to the United States in accordance with the terms of the Adams-Onís Treaty.21 As they always were in colonization, the Indians were caught in the crossfire of Huguenot-Catholic conflict in trying to adjust to this rapidly shifting landscape. A European Reformation shook not only France and Spain, but even the shores of Florida.

Matthew Pearson is a 13th-generation American and 4th-generation Tampa Floridian. He has written for American Reformer and TruthScript, and he is also a co-host of the Irenic Protestants podcast. You can find him on Twitter (@_matthewpearson).

M. Adele Francis Gorman, “Jean Ribault’s Colonies in Florida,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 44, no. 1/2 (1965): 51–66 (51).

New polemical methods employed by French Catholics against the Calvinists arose through a rediscovery of the works of Sextus Empiricus, a Greek philosopher who disputed the confidence in reason displayed by those such as Plato and Aristotle. Upon discovering these works, Catholic polemicists argued that if scripture is the sole infallible authority and one can only use fallible human reasoning to derive meaning from the text, there can be no human certainty. Thus, one should give up his use of reason and submit to the Roman magisterium to interpret scripture rather than rely on his own private judgment. For more on this, see Richard H. Popkin, “Skepticism and the Counter-Reformation in France,” Archiv Für Reformationsgeschichte – Archive for Reformation History 51, no. jg (1960): 58–87.

Gorman, “Jean Ribault’s Colonies in Florida,” 52.

William S. Goldman, “Spain and the Founding of Jamestown,” The William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 3 (July 2011): 427–450 (429–430).

Ibid., 443.

Paul E. Hoffman, “The Chicora Legend and Franco-Spanish Rivalry in La Florida,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 62, no. 4 (April 1984): 419–438 (433).

Ibid., 419.

Ibid., 434.

Louis J. Mendelis, “Colonial Florida,” Publications of the Florida Historical Society 3, no. 2 (October 1924): 4–15 (6–7).

Ibid., 8.

W.W. Ehrmann, “The Timucua Indians of Sixteenth Century Florida,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 18, no. 3 (January 1940): 168–191 (170).

Alejandra Dubcovsky and George A. Broadwell, “Writing Timucua: Recovering and Interrogating Indigenous Authorship,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 15, no. 3 (2017): 409–441 (416).

Mendelis, “Colonial Florida,” 8.

Gorman, “Jean Ribault’s Colonies in Florida,” 56.

Ibid., 57.

Ibid., 58.

Ibid., 59.

Mendelis, “Colonial Florida,” 9.

Amy Bushnell, “‘That Demonic Game’: The Campaign to Stop Indian Pelota Playing in Spanish Florida, 1675–1684,” The Americas 35, no. 1 (July 1978): 1–19 (6, 12).

Ibid., 18.

“European Exploration and Colonization,” Florida Department of State. Accessed June 14, 2024.

Thank you for posting, gentlemen!

Great work!